Student absences spiked during COVID-19, analysis finds

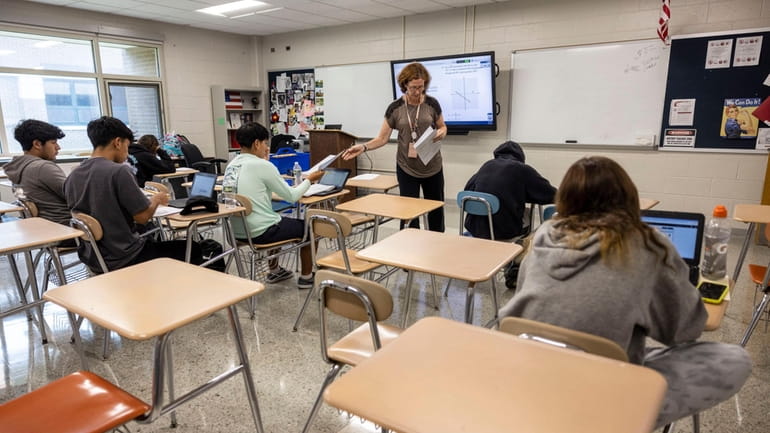

For more than two years after COVID was first detected on Long Island in 2020, learning was persistently disrupted and absences rose. Summer school classes, such as this one at East Hampton High School, have helped students make up ground.

Credit: Newsday/Alejandra Villa Loarca

Student absences surged on Long Island during the COVID-19 pandemic, a Newsday analysis found, leading education experts to fear that the learning losses could hamper children's academic progress for years.

The analysis revealed a growing disparity, as some systems saw improvement in attendance last school year, while others worsened, exacerbating what was considered a crisis even before the pandemic hit, according to chronic-absence data released by the state Education Department and obtained by Newsday from select Island districts.

Research has shown that students who chronically miss school are less likely to read proficiently and more likely to drop out of high school.

“We may have a whole cohort of kids moving through the system that will hit adulthood as a large group as a population with significant deficiencies,” said Sandy Addis, chairman of the National Dropout Prevention Center based in upstate Ballston Spa.

Students of color, students with disabilities, those who are homeless, and English-language learners were hit harder, with higher-than-average absences.

“We have a widening gap,” said Hedy Chang, executive director of Attendance Works, a national organization whose mission is to reduce chronic absence. “The gap is wider not because the kids at the top are getting better. They're just holding steady. It's because the situation for the kids who have had least access to resources has gotten worse during the pandemic.”

For more than two years — from March 2020, when the coronavirus was first detected on the Island, through the 2021-22 school year — student learning was persistently disrupted by quarantines, school closures and inconsistent instruction that at times was remote, hybrid or in-person. During that time, absences spiked.

In 2020-21, the number of Island students who missed nearly a month of school or more rose to more than 62,800, or 16%, of roughly 400,000 students, from about 46,800 in 2018-19, the school year before the pandemic, according to state data.

The state has yet to release absence data for 2021-22, but through Freedom of Information Law requests, Newsday obtained reports from 40 Island districts, a sampling of those that had the highest and lowest chronic absence rates based on the 2020-21 year.

The latest school year showed that, despite recovery in some places, alarmingly high absences persisted.

Even before the pandemic, federal education officials called chronic absenteeism — when a student misses 10% or more of instructional days — “a hidden educational crisis.” Nationwide, that rate has more than doubled during the pandemic, experts said.

In New York, chronic absenteeism is defined as a student not in school — excused and unexcused — for 10% or more of enrolled school days, which typically means 18 out of the minimum 180 instructional days in a school year.

Last school year, the rate of chronic absenteeism surged in some districts by as much as five times when compared to before the pandemic.

Amityville, for example, saw 84% of its 3,047 students chronically absent in 2021-22, up from 13% in 2018-19, according to district data. In Hempstead and Uniondale, more than 50% of students were absent for weeks last school year.

"It's hard to imagine what it must be like to work or go to school … with over half the kids being chronically absent," said Abe Fernández of Children's Aid, a New York City-based organization that works to help children in poverty. "That is just alarming."

When students are not in school, they miss out not only on instruction but also relationship-building with their teachers and peers, educators and experts said. They also lose out on access to resources that may help them. And when they return, they are more likely to have trouble following coursework, which could further perpetuate the cycle of more absences.

To help those students catch up, teachers may need to adjust lesson plans, which slows the entire class’ learning progression. The effect of chronic absence, especially on a large scale, also goes beyond individual classrooms.

“It impacts the school culture [and] what the school is able to achieve,” said Dafny Irizarry, president of the Long Island Latino Teachers Association.

Unique Redd has seen the impact of student absence firsthand. Redd, a 1995 Hempstead High School graduate, is part of a team of three at the high school’s attendance office.

Before the school year started, she and others held a meeting with parents of students who had troubling attendance in eighth grade. Before the teenagers started high school, the attendance team and several administrators wanted to see how they could help those students get back to school consistently.

Parents pointed to COVID-19 exposure and inclement weather. In conversations Redd had with families, they also mentioned lack of transportation. Hempstead schools do not offer transportation for students, except those with special needs, according to James Clark, assistant superintendent for special programs at the district.

Redd and others pointed to the taxi service or bus routes that can drop students near the school.

“As a mother raising three kids in Hempstead, I understand the struggles,” Redd said. “In Hempstead, we have a huge community of displaced students. Some mornings, I get out on the street, I see the moving vans that come for the families. It makes me sick when I see that van. I think some of my kids may be affected by this.”

Hempstead, one of the largest districts on the Island with more than 6,000 students, struggled with attendance before the pandemic. In 2018-19, the district’s chronic absenteeism rate was 42%. It rose to 54% in 2021-22.

Clark said the district has hired a bilingual social worker to work on attendance at the middle school.

“Dealing with attendance is a social issue, not always just an absence issue,” he said. “That's the battle because we know if we get them here, we can engage them. But there's sometimes environmental factors.”

Fernández, with Children's Aid, cautioned against pointing blame at a student, parent or school for high absences.

“When you get to a number like [50%], that can't just be individual parents making poor choices,” he said. “That speaks to a systemic issue that we have to address systemically and not just wag our finger at parents for being bad parents or punishing the kid.”

The numbers, Fernández said, are a call for communities to examine the data, find the root cause and mobilize resources to address it. "My hope is that people see this as a call to action, not a call to blame people," he said.

During the pandemic, districts that had low chronic absences saw their numbers rise, too.

Herricks schools, for example, saw its rate of chronic absenteeism nearly triple, from 3% in 2018-19 to 8% in 2021-22. Half Hollow Hills had its rate spike from 8% to 19% over the same span.

Educators pointed to student mental health issues, mandatory quarantines and multiple COVID-19 waves that during the worst of last winter shut down some schools for days.

“You have COVID. You have regular illnesses. Then you have sports-related injuries. Then you have school refusal, or school phobia. Then you have kids having social, emotional issues,” said East Hampton schools Superintendent Adam Fine, whose district saw its percentage of chronically absent students more than triple, from 9% in 2018-19 to nearly 30% in 2021-22.

In March 2020, schools shut down and officials developed plans for education alternatives such as remote learning as they waited for buildings to reopen. That fall, schools reopened with a hybrid model, in which districts offered remote and in-person instruction. Attendance was difficult to track that year as teachers scrambled to teach in two formats, and the resulting data may not even fully reflect student disengagement.

“You don't really know how many kids universally tuned out a teacher while they were sitting in front of a computer,” Fine said. “But I would hedge to bet that that is the case in a lot of schools.”

The 2021-22 school year was the first time students returned to their classrooms in person full time.

Selena Juarez, a senior at Riverhead High School, missed a lot of school days in 2020, when she became ill with COVID-19. Online instruction was difficult for her to navigate.

“I wasn't able to get up and be on the screen because I was just so sick that I didn't even want to do anything,” she said in an interview over the summer. “I had no motivation to do anything at all.”

Last winter, a second bout of COVID-19 kept her home for weeks, she said. Her grades suffered, and she had to take geometry during the summer to recover the credit.

Because much of learning, in particular math, is layered by units, missing days, let alone weeks, of classes can make it difficult for a student to catch up, said Chang, with Attendance Works.

“Let's say a kid misses 5 or 10 days because they're quarantined. If there is no support for you to keep learning your algebra, your geometry, even basic history, and there's no way to know what was happening in class, when you come back after those 10 days, you're really lost,” Chang said.

A full return to learning in person was a difficult adjustment for some.

Sabra Harry, a junior at Westhampton Beach High School, preferred remote learning because she could focus better in an environment devoid of distractions.

When school went back to in-person last fall, it was such an adjustment that she started skipping school. Toward the end of the school year, she was missing at least a day every week.

“I had kind of lost the ability to concentrate around other people because I got so used to being at home with quietness and no distractions,” she said.

Because she found it hard to focus in school, she would delay doing her homework. Some days, she stopped going to school or left in the middle of the day to study at home. But she knew she wasn’t getting everything she would in a classroom.

Harry, who used to get marks in the high 90s, found her grades drop into the high 80s and low 90s. She passed all her classes and was on the honor roll but felt she didn’t meet the standards she set for herself.

So far this year, Harry hasn't missed a day of school, she said this week, though she still feels she’s not 100% back to how she used to perform.

“When I see that I'm losing my rhythm, I've been making extra efforts to stop myself from going back to those old habits,” she said.

With the return of students like Harry, many districts saw a recovery in attendance last year. But educators and experts agree that the educational whiplash of the past two years will continue.

“There's too much COVID PTSD in the kids right now,” said Fine, the schools chief in East Hampton.

Chang said data from Connecticut showed that attendance slightly improved in the first month of this school year but was still worse than pre-pandemic years.

“It means that we haven't reconnected kids back to school,” she said. “Some of the kids who missed out a lot on school … might be feeling academically insecure because of how much school they missed.”

Experts said now is the time for Long Island schools, which have designated more than $200 million in federal pandemic-relief money to spend over the current school year, to direct some of that funding to reducing absence.

Schools have hired more mental health professionals and expanded programs such as summer school and tutoring, but the students who are not in school cannot benefit from those resources, they said.

Fernández, with Children's Aid, used after-school programs as an example. If an after-school program is run on a first-come, first-served approach, he said it’s worth considering reserving slots to incentivize students to attend school regularly.

“After-school is a protective factor in attendance that if kids are looking forward to what's happening in after-school, they're more likely to want to come to day school,” he said. “So if we know that and we know which kids are chronically absent, does it make sense to make it first come, first serve?”

Experts also stressed investing in relationship-building to get students to consistently attend school.

“You may have remembered back to our school days: There was that one teacher, that one coach, that one person in the school building that we really felt a connection with,” said Addis, with the National Dropout Prevention Center. “They paid attention to us. They took an interest in us. We felt a little bit accountable to them to be in school, and if we weren't at school, they asked us the next day, 'Where were you? I missed you yesterday.' ”

“We missed you yesterday” is what Irizarry said to her students to let them know their absence was noticed.

“It is to show you belong here,” she said. “I do think that when they know that they belong here, they want to be here.”

With Arielle Martinez

Student absences surged on Long Island during the COVID-19 pandemic, a Newsday analysis found, leading education experts to fear that the learning losses could hamper children's academic progress for years.

The analysis revealed a growing disparity, as some systems saw improvement in attendance last school year, while others worsened, exacerbating what was considered a crisis even before the pandemic hit, according to chronic-absence data released by the state Education Department and obtained by Newsday from select Island districts.

Research has shown that students who chronically miss school are less likely to read proficiently and more likely to drop out of high school.

“We may have a whole cohort of kids moving through the system that will hit adulthood as a large group as a population with significant deficiencies,” said Sandy Addis, chairman of the National Dropout Prevention Center based in upstate Ballston Spa.

WHAT TO KNOW

- Student absences surged on Long Island during the COVID-19 pandemic, a Newsday analysis found, fueling fears that the learning losses could hamper children's academic progress for years.

- On the Island, the number of students who missed more than 18 days of school rose from roughly 46,800 in 2018-19, the year before the pandemic, to more than 62,800 in 2020-21. Despite recovery in some districts last school year, alarmingly high student absences persisted.

- Students who consistently miss school are less likely to read proficiently and more likely to drop out of high school.

Students of color, students with disabilities, those who are homeless, and English-language learners were hit harder, with higher-than-average absences.

“We have a widening gap,” said Hedy Chang, executive director of Attendance Works, a national organization whose mission is to reduce chronic absence. “The gap is wider not because the kids at the top are getting better. They're just holding steady. It's because the situation for the kids who have had least access to resources has gotten worse during the pandemic.”

For more than two years — from March 2020, when the coronavirus was first detected on the Island, through the 2021-22 school year — student learning was persistently disrupted by quarantines, school closures and inconsistent instruction that at times was remote, hybrid or in-person. During that time, absences spiked.

In 2020-21, the number of Island students who missed nearly a month of school or more rose to more than 62,800, or 16%, of roughly 400,000 students, from about 46,800 in 2018-19, the school year before the pandemic, according to state data.

The state has yet to release absence data for 2021-22, but through Freedom of Information Law requests, Newsday obtained reports from 40 Island districts, a sampling of those that had the highest and lowest chronic absence rates based on the 2020-21 year.

The latest school year showed that, despite recovery in some places, alarmingly high absences persisted.

Even before the pandemic, federal education officials called chronic absenteeism — when a student misses 10% or more of instructional days — “a hidden educational crisis.” Nationwide, that rate has more than doubled during the pandemic, experts said.

In New York, chronic absenteeism is defined as a student not in school — excused and unexcused — for 10% or more of enrolled school days, which typically means 18 out of the minimum 180 instructional days in a school year.

Last school year, the rate of chronic absenteeism surged in some districts by as much as five times when compared to before the pandemic.

Amityville, for example, saw 84% of its 3,047 students chronically absent in 2021-22, up from 13% in 2018-19, according to district data. In Hempstead and Uniondale, more than 50% of students were absent for weeks last school year.

"It's hard to imagine what it must be like to work or go to school … with over half the kids being chronically absent," said Abe Fernández of Children's Aid, a New York City-based organization that works to help children in poverty. "That is just alarming."

An empty-desk crisis

When students are not in school, they miss out not only on instruction but also relationship-building with their teachers and peers, educators and experts said. They also lose out on access to resources that may help them. And when they return, they are more likely to have trouble following coursework, which could further perpetuate the cycle of more absences.

To help those students catch up, teachers may need to adjust lesson plans, which slows the entire class’ learning progression. The effect of chronic absence, especially on a large scale, also goes beyond individual classrooms.

“It impacts the school culture [and] what the school is able to achieve,” said Dafny Irizarry, president of the Long Island Latino Teachers Association.

Unique Redd is part of a team of three at Hempstead High School’s attendance office. “As a mother raising three kids in Hempstead, I understand the struggles,” she said.

Credit: Danielle Silverman

Unique Redd has seen the impact of student absence firsthand. Redd, a 1995 Hempstead High School graduate, is part of a team of three at the high school’s attendance office.

Before the school year started, she and others held a meeting with parents of students who had troubling attendance in eighth grade. Before the teenagers started high school, the attendance team and several administrators wanted to see how they could help those students get back to school consistently.

Parents pointed to COVID-19 exposure and inclement weather. In conversations Redd had with families, they also mentioned lack of transportation. Hempstead schools do not offer transportation for students, except those with special needs, according to James Clark, assistant superintendent for special programs at the district.

Redd and others pointed to the taxi service or bus routes that can drop students near the school.

“As a mother raising three kids in Hempstead, I understand the struggles,” Redd said. “In Hempstead, we have a huge community of displaced students. Some mornings, I get out on the street, I see the moving vans that come for the families. It makes me sick when I see that van. I think some of my kids may be affected by this.”

Hempstead, one of the largest districts on the Island with more than 6,000 students, struggled with attendance before the pandemic. In 2018-19, the district’s chronic absenteeism rate was 42%. It rose to 54% in 2021-22.

Clark said the district has hired a bilingual social worker to work on attendance at the middle school.

“Dealing with attendance is a social issue, not always just an absence issue,” he said. “That's the battle because we know if we get them here, we can engage them. But there's sometimes environmental factors.”

Fernández, with Children's Aid, cautioned against pointing blame at a student, parent or school for high absences.

“When you get to a number like [50%], that can't just be individual parents making poor choices,” he said. “That speaks to a systemic issue that we have to address systemically and not just wag our finger at parents for being bad parents or punishing the kid.”

The numbers, Fernández said, are a call for communities to examine the data, find the root cause and mobilize resources to address it. "My hope is that people see this as a call to action, not a call to blame people," he said.

A crisis compounded

During the pandemic, districts that had low chronic absences saw their numbers rise, too.

Herricks schools, for example, saw its rate of chronic absenteeism nearly triple, from 3% in 2018-19 to 8% in 2021-22. Half Hollow Hills had its rate spike from 8% to 19% over the same span.

Educators pointed to student mental health issues, mandatory quarantines and multiple COVID-19 waves that during the worst of last winter shut down some schools for days.

“You have COVID. You have regular illnesses. Then you have sports-related injuries. Then you have school refusal, or school phobia. Then you have kids having social, emotional issues,” said East Hampton schools Superintendent Adam Fine, whose district saw its percentage of chronically absent students more than triple, from 9% in 2018-19 to nearly 30% in 2021-22.

In March 2020, schools shut down and officials developed plans for education alternatives such as remote learning as they waited for buildings to reopen. That fall, schools reopened with a hybrid model, in which districts offered remote and in-person instruction. Attendance was difficult to track that year as teachers scrambled to teach in two formats, and the resulting data may not even fully reflect student disengagement.

“You don't really know how many kids universally tuned out a teacher while they were sitting in front of a computer,” Fine said. “But I would hedge to bet that that is the case in a lot of schools.”

The 2021-22 school year was the first time students returned to their classrooms in person full time.

Selena Juarez, a Riverhead High School senior, missed a lot of school in 2020. Last winter, a second bout of COVID-19 kept her home for weeks, she said.

Credit: Morgan Campbell

Selena Juarez, a senior at Riverhead High School, missed a lot of school days in 2020, when she became ill with COVID-19. Online instruction was difficult for her to navigate.

“I wasn't able to get up and be on the screen because I was just so sick that I didn't even want to do anything,” she said in an interview over the summer. “I had no motivation to do anything at all.”

Last winter, a second bout of COVID-19 kept her home for weeks, she said. Her grades suffered, and she had to take geometry during the summer to recover the credit.

Because much of learning, in particular math, is layered by units, missing days, let alone weeks, of classes can make it difficult for a student to catch up, said Chang, with Attendance Works.

“Let's say a kid misses 5 or 10 days because they're quarantined. If there is no support for you to keep learning your algebra, your geometry, even basic history, and there's no way to know what was happening in class, when you come back after those 10 days, you're really lost,” Chang said.

A full return to learning in person was a difficult adjustment for some.

Westhampton Beach High School junior Sabra Harry studies at home. When school went back to in-person last fall, it was such an adjustment that she started skipping school.

Credit: Tom Lambui

Sabra Harry, a junior at Westhampton Beach High School, preferred remote learning because she could focus better in an environment devoid of distractions.

When school went back to in-person last fall, it was such an adjustment that she started skipping school. Toward the end of the school year, she was missing at least a day every week.

“I had kind of lost the ability to concentrate around other people because I got so used to being at home with quietness and no distractions,” she said.

Because she found it hard to focus in school, she would delay doing her homework. Some days, she stopped going to school or left in the middle of the day to study at home. But she knew she wasn’t getting everything she would in a classroom.

Harry, who used to get marks in the high 90s, found her grades drop into the high 80s and low 90s. She passed all her classes and was on the honor roll but felt she didn’t meet the standards she set for herself.

So far this year, Harry hasn't missed a day of school, she said this week, though she still feels she’s not 100% back to how she used to perform.

“When I see that I'm losing my rhythm, I've been making extra efforts to stop myself from going back to those old habits,” she said.

Seeking more investment

With the return of students like Harry, many districts saw a recovery in attendance last year. But educators and experts agree that the educational whiplash of the past two years will continue.

“There's too much COVID PTSD in the kids right now,” said Fine, the schools chief in East Hampton.

Chang said data from Connecticut showed that attendance slightly improved in the first month of this school year but was still worse than pre-pandemic years.

“It means that we haven't reconnected kids back to school,” she said. “Some of the kids who missed out a lot on school … might be feeling academically insecure because of how much school they missed.”

Experts said now is the time for Long Island schools, which have designated more than $200 million in federal pandemic-relief money to spend over the current school year, to direct some of that funding to reducing absence.

Schools have hired more mental health professionals and expanded programs such as summer school and tutoring, but the students who are not in school cannot benefit from those resources, they said.

Fernández, with Children's Aid, used after-school programs as an example. If an after-school program is run on a first-come, first-served approach, he said it’s worth considering reserving slots to incentivize students to attend school regularly.

“After-school is a protective factor in attendance that if kids are looking forward to what's happening in after-school, they're more likely to want to come to day school,” he said. “So if we know that and we know which kids are chronically absent, does it make sense to make it first come, first serve?”

Experts also stressed investing in relationship-building to get students to consistently attend school.

“You may have remembered back to our school days: There was that one teacher, that one coach, that one person in the school building that we really felt a connection with,” said Addis, with the National Dropout Prevention Center. “They paid attention to us. They took an interest in us. We felt a little bit accountable to them to be in school, and if we weren't at school, they asked us the next day, 'Where were you? I missed you yesterday.' ”

“We missed you yesterday” is what Irizarry said to her students to let them know their absence was noticed.

“It is to show you belong here,” she said. “I do think that when they know that they belong here, they want to be here.”

With Arielle Martinez