Blood donor 'lifers' on why they give

Every time a bag of blood was hooked up to Radha Persaud’s husband, the change she saw on the hospital monitors was instant.

“His vitals would be dropping, his blood pressure, his heart rate, everything would be dropping, and as soon as they put in new blood, everything would come right back up,” she said. “I thought it was amazing that this stranger, who didn’t know us, would donate blood to save his life.”

Her husband died in 2011 of kidney disease complications, but her gratitude never perished. She has donated 5 gallons of blood products since 2010 and tries to give blood-clotting platelets at least once a month, or as often as health rules allow.

“I want to do what someone did for me 12 years ago,” said Persaud, 39, a Hewlett resident in the luggage industry.

Star blood donors like Persaud form the backbone of the New York Blood Center, a nonprofit that supplies hospitals and medical facilities in several states. Many have donated for decades, getting to know other blood donors, making friends among staff and celebrating one another’s birthdays. For a lot of them, no reminders or rewards, such as gift cards, are needed to appear at one of the nonprofit’s 52 donation centers as they commit to what could be 20 minutes or two hours, depending on whether they are giving whole blood, oxygen-rich red blood cells, platelets or antibody-rich plasma.

Nassau County police officer Luis Serrano donated blood this month at police headquarters in Mineola. He is grateful to donors of the past, who saved the life of his mother when she was born. Credit: Newsday/Steve Pfost

At a time when the pandemic has stunted the supply of blood products, reliable donors have been the life-force staving off critically low rates in areas where the blood bank operates, including New York, New Jersey and Connecticut and other states.

“The majority of blood donors give once and don’t come back for years or never come back,” said Andrea

Cefarelli, New York Blood Center’s senior vice president of corporate communication. “There’s a small portion of the community sort of carrying the weight of providing an ample blood supply for the community. Then there are these amazing people that make a lifetime out of giving.”

‘Most human thing’

Because the region’s population is so diverse, New York Blood Center has the largest inventory of rare blood in the world. Credit: Corey Sipkin

Only 4% of the population gives blood, she said. Out of the donors, about 10% give blood five times a year and about 5% give both red blood and platelets at least 10 times during their lifetimes, she said. With January designated as National Blood Donor Month, Cefarelli acknowledges not everyone can donate but, she said, they can organize blood drives and be “compassionate influencers,” getting others to the phlebotomists.

“It’s the most human thing you can do, to give a part of yourself,” said Mary Jiritano, 62, of Kings Park.

She has donated 41 gallons over 335 visits since high school, and she has gotten an unexpected reward. About 15 years ago, she said, she was called to give platelets for a cancer patient at North Shore University Hospital in Manhasset whose name she happened to see on the donation bag. A year later, she saw a photo in Newsday of a 10-year-old former leukemia patient with the same name pointing to his artwork at the hospital.

Cefarelli said she could not find records of this direct donation but said names are sometimes put on blood bags when the donor and recipient are family members.

But Jiritano believes it could have been the boy in the photo who got her platelets — and she relishes the thought of his recovery. “That was the best thing,” she said. “If there was any reason to keep going, that was it. I still have the photograph. Every once in a while, I take it out and look at it, and I wonder how he’s doing now.”

Lt. Robert Connolly gives blood during the New York Blood Center blood drive at Nassau County police headquarters on Jan. 4. Credit: Newsday/Steve Pfost

For other regulars, their reasons for giving and giving bring them to tears.

When asked why he had increased the pace of his donations since his first one 40 years ago in college, Charles Kalinowski said it’s partly guilt and grief. That was around the time his younger brother broke his neck during a pole-vault competition and became quadriplegic; he died in 2004.

“I just started giving . . . to somehow assuage the guilt of being the healthy, older brother,” said Kalinowski, 63, who lives in Amityville and teaches chemistry at St. Dominic High School in Oyster Bay.

He has donated 54 gallons during more than 400 visits. Platelets each month had been his specialty for years, but now that his platelet count is lower, he gives “double red,” just the red blood cells from about 2 pints of blood (the platelets and plasma go back to the donor).

“I had two cousins with cystic fibrosis,” Kalinowski said. “When we went to visit them, it was always a kind of helpless feeling. You don’t want to see people sick, and you do what you can to help people not be sick.”

Route to recipient

A worker at New York Blood Center’s Long Island City facility puts blood bags together to be sent to a hospital. Credit: Corey Sipkin

After donors give, their blood begins a voyage that can take three days to get ready for recipients.

Several times a day, coolers arrive at New York Blood Center’s lab in Long Island City from its donation centers as well as community blood drives at churches, businesses and other places. Each bag of blood and its products have a unique code with the donor’s confidential information, and details are logged into the nonprofit system at each stop along the way.

At the facility, each bag of whole blood is pressed to squeeze the plasma to the top and into another sterile bag. The plasma is kept in a freezer at minus-22 degrees Fahrenheit. Platelets undergo a process to inactivate pathogens and bacteria, then are stored at room temperature (about 68 to 75 degrees) on racks that gently rock to prevent coagulation.

Tubes of blood collected with each donation are sent to be tested at the nonprofit’s laboratory in Providence, Rhode Island. The blood is screened for properties including blood type, specific antigens and a wide range of viruses and bacteria. If a medical condition is detected, sickle cell anemia or HIV, for example, donors are told they are not eligible to donate because their blood cannot be used.

Each bag of plasma is logged into the computer at New York Blood Center’s Long Island City lab. Credit: Corey Sipkin

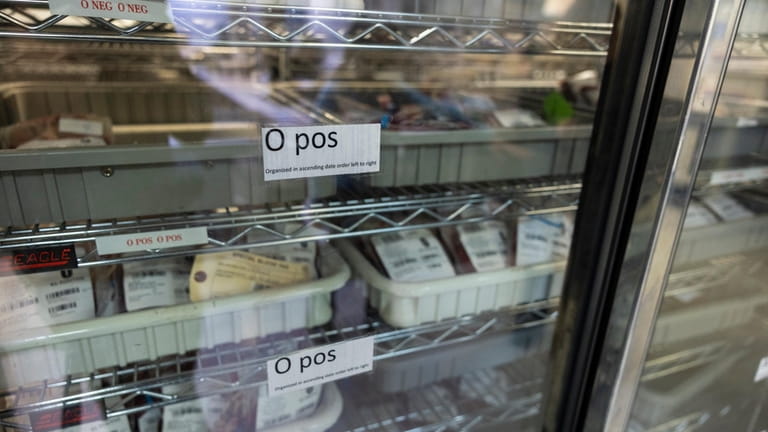

Blood and blood components that have passed all tests are stored at the Long Island City facility until a hospital or doctor orders them. The bags of blood ready for transfusions are kept on trays in rooms at about 35 to 46 degrees, with each tray denoting blood type and other identifiers. O negative is the most valued because everyone can receive it, but only 6% to 8% of people have it. Some bags are labeled with “Code 96” or “Code 99,” a rare designation meaning they don’t have the antigens or combination of markers in most of the population; the lack of antigens is frequently crucial for newborns who need transfusions.

The transportation room at the Long Island City facility tracks the nonprofit’s vans and trucks as they move their precious cargo.

Because of the racial diversity in the metropolitan region, New York Blood Center has the largest inventory of rare blood in the world, Cefarelli said. Last year, 71.6% of its donors were white, 11.7% Latino, 7.7% Asian and 4.4% Black, with the remaining donors of American Indian or of mixed race.

Frequent donor Radha Persaud of Hewlett gets her blood drawn at the New York Blood Center in Rockville Centre by Eazyara Peña of South Ozone Park. Credit: Brittainy Newman

‘We’ll be in trouble’

For the past three years, New York Blood Center has been grappling with three challenges — the impact of the pandemic, the need to infuse the blood supply with younger donors, and the worry that the message about its critical shortage is getting “old.”

“There’s no surplus in the world right now, and that’s why it’s been so critical,” Cefarelli said. “We’ve been relying on our regular blood donors, and we’ve even been talking to people who have not donated in five to 20 years.”

The pandemic stopped the flow from blood drives held by businesses, whose employees began working remotely, and deterred donors who didn’t want to go out and possibly catch COVID-19.

“The pandemic really devastated the foundation on which we really collect blood,” Cefarelli said. “We’re slowly recovering, but we’re not quite there.”

The drop in donations comes as the blood bank’s most active givers are at least 40 years old. “As these super blood donors age out, if we don’t replace with a new generation of life savers,” she said, “we’ll be in trouble.”

Since high school and college students began attending remote classes, the center has had to rebuild relationships to persuade younger generations to organize blood drives and to donate. In the past two years, for example, the New York Blood Center has employed humor in ads streaming at gas stations, on billboards and more to reach young people and others.

“We say giving blood hurts less than running into your ex with spinach in your teeth or biting into hot pizza,” Cefarelli said. “Using humor is really important to keep it in people’s minds without constantly having it be a crisis, which it really has been during the pandemic.”

Lab manager Michael Wurst checks on agitators that keep platelets in motion at the Long Island City NYBC lab. Credit: Corey Sipkin

The New York Blood Center experienced five blood supply emergencies last year, more than the usual couple of times a year, she said. The demand for blood has been greater than pre-pandemic, she said, possibly because people are getting medical care postponed during the pandemic.

That has left the supply hovering at one to three days instead of the more optimal seven to 10 days’ supply. For O negative, the supply has often been just one day.

“As you can see, we need more,” Cefarelli said at the lab, gazing at half-empty blood storage trays. “December and January were always hard, but not this hard.”

Last year, the blood bank attracted 172,500 donors, according to the nonprofit, but it takes a donor base of at least 200,000 people, making 32,000 donations a month, to create a seven- to 10-day supply.

Anne Marie Appell, 71, of Garden City, who likes to tout her large veins, said she has donated blood about 400 times in about 40 years and enjoys seeing her platelets whirl “like a white tornado” in a centrifuge that spins the blood to separate the cells. The process of donating platelets has taken some donors as long as three hours, depending on the volume of platelets in their blood.

When she turns 76, she’ll need a doctor’s note or the approval of an NYBC medical director to continue giving blood. She’s tried to convince relatives in the younger generations to give blood, too.

“There’s no substitute,” the retiree said. “I’m going to do it until I can’t do it anymore. I’m a blood donor lifer.”

‘A father-son thing’

Lin Dastis, left, needed blood during pregnancy. In gratitude, her son, Peter, and her husband, Pete, have donated together for years. Credit: Randee Daddona

The effort to build a pipeline of donors is one taken seriously by longtime givers like Pete Dastis, 67, who persuaded his son, Peter, 29, to join him 11 years ago, when he was a high school junior.

“Oh, Peter and Peter are here,” the elder Dastis, a retired carpenter, said he hears when he and his son arrive at a donation site. The duo donated together every month for years, sitting in chairs across from each other, with the father having donated 53 gallons even though he hates needles.

“I saw how important it was to my dad and that inspired me to go,” said the son, who started donating at age 18 and is now working on his bachelor’s degree in business analytics at Farmingdale State College. “We usually go out to eat afterwards as a father-son thing.”

And there will always be donors like Nassau County police officer Luis Serrano, 36, who describes himself as a beneficiary of blood donation.

That’s why he was at police headquarters in Mineola early this month, when 57 pints of whole blood were donated at the drive organized by the Nassau County Police Benevolent Association, the Nassau County Police Superior Officers Association and the Nassau County Police Detectives’ Association.

When his grandmother was pregnant with his mother, Serrano said, she rejected doctors’ advice to abort the baby because of complications.

The day Serrano’s mother was born, she needed a complete blood transfusion, the officer said.

He’s given blood about three times a year for the past six years, repaying what he sees as a debt to society.

“All the blood she got was from somebody else,” he said. “Without her, I would not be here.”

Giving blood

The New York Blood Center is on Vernon Blvd. in Long Island City Tuesday, Dec. 27, 2022, in New York. Credit: Corey Sipkin

Most adults have 8 to 12 pints of blood. To find out whether and how you can give blood, visit the New York Blood Center's website, nybc.org, which lists donation centers and community drives. In the screening process at the donation site, potential donors answer an online questionnaire, go through a short interview and have their vital signs taken (for example, blood pressure and a hematocrit to check their red blood count). After blood or its components are given, donors are asked to relax and have refreshments on site for about 15 minutes. Here are ways to donate:

- Whole blood donation: About a pint of blood is taken, with the red blood cells, plasma and platelets separated later. Most community blood drives take whole blood because the other types of donations require technology generally kept at the blood bank’s centers. Donors must be at least 17 (16 with written permission of parent/guardian) and weigh at least 110 pounds. Type O negative blood is in high demand because everyone can receive it. Registration to refreshments takes about an hour; can be donated every 56 days.

- Double red: Only red blood cells are taken from 2 pints of whole blood, with the donor retaining the plasma and platelets. In addition to age requirements, donors must meet height and weight requirements: 130 pounds and 61 inches tall for males; 150 pounds and 65 inches tall for females. Red blood cells are crucial for many premature infants, who require up to four transfusions to survive, and people with blood disorders. Registration to refreshments takes about 75 minutes; can be donated every 16 weeks.

- Platelets: Platelets help cancer patients, accident victims and others with blood-clotting issues. An automated process spins the blood in a centrifuge to strip out the platelets. Because platelets are short-lived, they must be transfused within seven days. Registration to refreshments can take about 2½ hours to obtain the required volume of platelets; can be donated every seven days, up to 24 times a year.

- Plasma: A concentrated volume of plasma is taken from the blood in an automated process. Plasma, which carries nutrients, proteins and antibodies, is valuable for burn and accident victims and can be used to make products that fight infections and diseases. Plasma from AB blood is in high demand because it is the only type that can be safely transfused to anyone in an emergency. Registration to refreshments takes about 75 minutes; can be donated every 28 days.

Source: New York Blood Center

Teacher salaries ... Cold Spring Hills back in court ... SCCC tuition hike ... FeedMe: Omakase Sushi