Regents exams in spotlight as educators consider other paths toward graduation

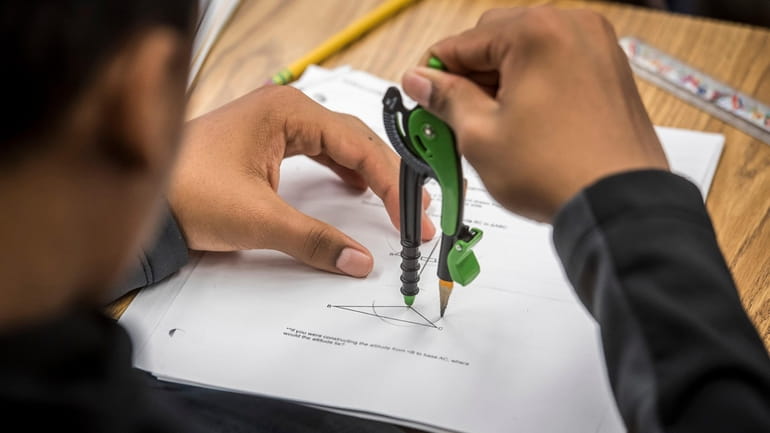

A student works on a geometry problem at Plainview-Old Bethpage John F. Kennedy High School in Plainview. Starting in the fall, a "blue-ribbon" commission of about 40 educators, parents, business representatives and others is to review the state's complex graduation requirements and recommend changes. Credit: Newsday/J. Conrad Williams Jr.

Regents exams — gatekeepers to high school diplomas for more than 140 years — face intense scrutiny in the months ahead, as education leaders look for equivalent ways to boost graduation rates for students struggling to pass the tests.

Starting in the fall, a "blue-ribbon" commission of about 40 educators, parents, business representatives and others will review the state's complex graduation requirements and recommend changes. State education officials said they expect a detailed inquiry into the knowledge and skills that students need in the 21st century, and that a final commission report should be delivered in 2024 or 2025.

There are 10 Regents exams in all, and students by state rules normally have to pass four or five before receiving a diploma. Exams usually are taken during students' four years in high school, though there is heavy "accelerated" testing in middle schools as well.

The state's Board of Regents, which approves diploma standards, is taking short-term steps to relax some rules for students whose learning may have been disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. In May, the board agreed to allow local school superintendents to award graduation credit to students for exam scores as low as 50, down from the normal passing score of 65. That change expires in 2023.

In October, Regents are scheduled to consider another provision, allowing superintendents to award credit to students scoring below 50. Such credit would be used in earning "local" diplomas, rather than the more challenging Regents diplomas, and would apply only to students who were unable to graduate in June.

Across Long Island and statewide, dozens of advocacy groups have lined up to voice either support or opposition for revamping graduation requirements. State education officials have insisted the diploma review — the most sweeping of its kind in a quarter-century — does not represent an effort to dilute standards.

"Let me be clear — this effort is not about doing away with the Regents exam," said state Education Commissioner Betty A. Rosa, in a message posted on her department's website. "Rather, it's about providing different avenues, equally rigorous, for students to demonstrate that they are ready to graduate with a meaningful diploma."

State education Chancellor Betty A. Rosa defended "providing different avenues" for students to demonstrate that they're ready to graduate "with meaningful diplomas." Credit: Hans Pennink

Rosa, a former Bronx schools superintendent, chaired the Regents board from 2016 to 2020.

Roger Tilles, of Manhasset, who represents Long Island on the Regents board, said in a phone interview that the review would "be effective in coming up with new graduation requirements that are relevant."

"It's just slower than I would like," Tilles added.

A call to preserve exam on history, government

Opponents of revised diploma requirements said Regents exams face a potential downgrade in status, even if they are not eliminated entirely. The Long Island Council for the Social Studies, representing 1,100 school supervisors and teachers, said it fears especially for the future of a three-hour Regents exam in United States History and Government.

Council leaders, who noted that the history exam has been canceled for three years running, have pushed Rosa to give them a seat on the advisory commission.

History exams, unlike those in English, math and science, are not required by federal law. Nonetheless, social studies representatives said tests in the history and civics courses they teach deserve as much attention as tests in other subjects.

"The values of America, its faults and its successes, are all built into its history, and it's important for students to know about this," said Gloria Sesso, a retired Suffolk County school administrator who serves as co-president of the social studies council. "Everything that's happened in Washington recently — the presidential electoral count, the Supreme Court decisions — are part of our history."

Gloria Sesso serves as co-president of the Long Island Council for the Social Studies. Credit: Kendall Rodriguez

In New York, most students who earn diplomas normally pass Regents exams in at least four subjects: English, math, science and history. The state's original exams were first used to measure the academic quality of high schools in 1878.

A federal law, the Every Student Succeeds Act or ESSA, requires all students to take state exams in English, math and science once during their high school years. States, however, do not have to use such tests to determine students' eligibility for diplomas.

For this reason, New York State, if it chooses to do so, could allow students to demonstrate their qualifications through "alternative" assessments. Possible options already suggested include scores based on students' oral presentations of research projects, or scores based on portfolios of students' writing.

Differing views of Regents exams' role

Any such shift could ignite a statewide fight.

Supporters of Regents exams have combined in a group called the New York Equity Coalition. The organization lists 27 members, including the Education Trust-New York, based in Manhattan; the Business Council of New York State, Albany; and the Urban League of Long Island, Plainview.

Equity Coalition representatives contended the Regents board has moved to make graduation standards more lenient. Representatives added that lax standards in high school can result in more students being forced to take remedial courses in college, and in a general lack of accountability.

On the other side is the Coalition for Multiple Pathways to a Diploma, another statewide group, which lists more than 80 members. They include Advocates for Children of New York, with a center in Manhattan; Learning Disabilities Association of New York State, Rochester; and Long Island Advocacy Center, New Hyde Park.

The multiple pathways group supports the Regents' drive to review graduation standards. Representatives said New York is among a minority of states that require students to pass multiple standardized exit exams, and that such tests pose an unnecessary barrier to students who have otherwise completed high school coursework and are ready for college or careers.

Roberta Grogan, of Seaford, is one of many parents who believe exams should be decoupled from graduation requirements, and that students should be given more options.

Grogan, who has applied to serve on the state commission, said her opinion was shaped by the experience of a son, now grown, who is on the autism spectrum, and who needed extensive tutoring during his student days to pass state exams and earn a Regents diploma.

Roberta Grogan, of Seaford, believes students should be given more pathways toward graduation. Credit: Newsday/J. Conrad Williams Jr.

"I see so many kids who think differently," Grogan said in a phone interview. "We need to be flexible in how we reward and award diplomas."

Another supporter of this "multi-pathway" route is Michael Hynes, superintendent of Port Washington schools. He noted that more than three dozen high schools across the state, mostly in New York City, already are allowed by the state to limit their use of Regents exams to the one in English. To demonstrate competence in other subjects, students write research reports and present them orally to outside evaluators.

"That's something that, I believe, Regents exams can't capture," Hynes told Newsday.

Such schools, organized in a "performance standards consortium," have operated for 20 years. Still, some experienced educators doubt this model could be duplicated on a mass basis.

One skeptic is Peter Goodman, a former high school social studies teacher and union leader in Brooklyn who now writes a blog on statewide educational issues. Goodman said the student evaluation systems used by consortium schools require a "totally different structure" than that found in traditional schools, and that policymakers should be wary in trying to substitute such evaluations for uniform testing.

"Regents exams are made up by teachers — they really reflect the state curriculum and what teachers are actually teaching," Goodman said in a phone interview. "I think we have a diploma that prepares kids for the world, and constantly chipping at Regents exams, as if it's a culprit, is the wrong way to go."

Brian Doelger, superintendent of Shelter Island schools, agreed that traditional exams still serve a purpose.

"I remember taking the Regents myself in high school. It was something I always prepared for," said Doelger, who also serves on the board of the regional social studies council. "I think it is important for students to have that motivating factor in any subject."

WHAT TO KNOW

- Regents exams face intense review in coming months, as a "blue-ribbon" commission examines those tests and other diploma standards with an eye toward change.

- Meanwhile, state education officials are taking short-term steps to relax rules for students unable to pass exams during COVID-19 outbreaks.

- Dozens of advocacy groups on Long Island and statewide are lining up, either in defense of traditional testing standards or sweeping change, in a debate that could last for years.