Antonio Cromartie an unlikely mentor for younger players dealing with financial issues

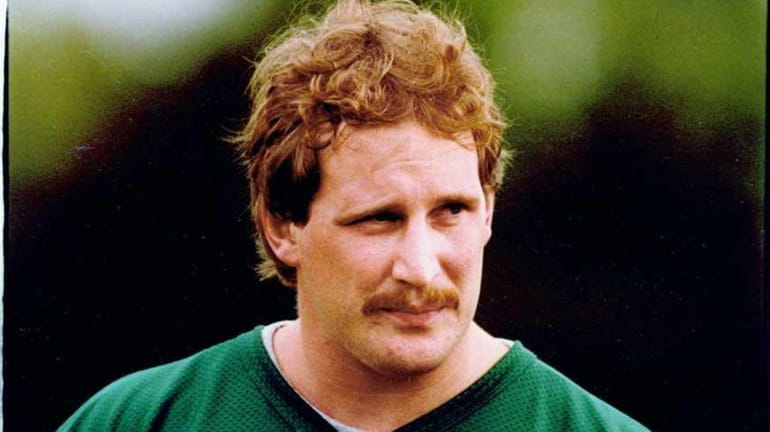

Defensive back Antonio Cromartie takes a knee during OTAs. (May 30, 2013) Credit: Mike Stobe

By his own count -- and he admits he might be underestimating just how bad it really was -- Jets cornerback Antonio Cromartie went through $5 million in his first two seasons in the NFL.

Poof. Just like that . . . all that cash -- which was almost all of the guaranteed money from his rookie contract with the San Diego Chargers -- and. . .

"Gone. Just gone," Cromartie said the other day during a conversation in the Jets' locker room.

The spending was non-stop: There were nine cars, two expensive homes, piles of jewelry, extravagant gifts and cash -- lots of cash -- to friends and family members who would simply ask, and shopping sprees that ran into the tens of thousands of dollars. Cromartie spent so much on so many things and so many people he can't even remember where it all went.

Take his automobile collection:

"I had two Dodge Chargers, probably spent $100,000 just fixing them up," he said. "I had a '65 Caprice, which I spent $100,000 on. I had two BMWs, two Escalades."

Cromartie doesn't remember the other two cars. And he said he came close to buying a Lamborghini, a car that can cost $500,000 or more.

"I was out of control," Cromartie said. "I remember [former Chargers teammate] Quentin Jammer used to tell me to slow down, but I couldn't do it. I just loved spending money."

But these days, Cromartie's favorite car is a Toyota Prius, a hybrid sedan that many middle class Americans drive. He brags about how little he spends on gas.

"I'll fill it up every 2 1/2 weeks or so, and I'm only spending 33 bucks, while everybody else is spending 80 or 90 bucks a tank," he said. "Right now, I'm all about saving money."

Can this really be the same guy, even after agreeing to a four-year, $32 million contract with the Jets in 2011? Is he really pinching pennies and watching every dollar? Has he truly matured as a person? Cromartie insists he has, as evidenced by his financial turnaround.

"Right now, I try to put away as much money as I possibly can and live on a budget," Cromartie said. "I learned the hard way."

The transformation from profligate spender to frugal consumer has been a stunning and unexpected one for Cromartie, who is now the one telling his younger teammates about the perils of over-spending.

Cromartie's off-field reputation is known more for the fact that he has 10 children with eight different women. But the 29-year-old cornerback, who is now married and has two children with his wife, Terricka, has since become an unlikely advocate about the virtues of financial responsibility.

"I want to help others learn from what I did wrong," said Cromartie, who has become the Jets' No. 1 cornerback now that Darrelle Revis has been traded. He is also taking on a greater leadership role in the locker room, and part of that approach is geared toward helping the Jets' younger players deal with financial issues.

"I tell the young guys, 'Don't spend any money the first year and a half of your career,'" Cromartie said. "You don't know what will happen after that. You might be released. You might be hurt. Just save your money."

Unfortunately, not enough players have heeded that advice. A 2009 survey by Sports Illustrated, for instance, estimated that close to 80 percent of retired NFL players went into bankruptcy, with even high-profile and highly compensated players experiencing financial hardship. Among the players in recent years to declare bankruptcy: Giants Hall of Fame linebacker Lawrence Taylor; Buccaneers Hall of Fame defensive tackle Warren Sapp; former Jaguars, Redskins and Jets quarterback Mark Brunell; former Lions first-round defensive lineman Luther Ellis; and former Raiders, Cowboys and Panthers wide receiver Raghib "Rocket" Ismail.

Cromartie knows he might have joined that casualty list if he hadn't changed his ways a few years ago. It wasn't until he sought help from a man named Jonathan Schwartz, a Certified Public Accountant with the financial services company GSO Business Management in Los Angeles, that Cromartie finally turned things around. Schwartz was recommended to Cromartie by the cornerback's agent, the late Gary Wichard.

But this was more than a typical business arrangement; Schwartz took the unusual step of inviting Cromartie to live at his home in Agoura Hills, Calif. for a couple of weeks. Schwartz, 43, who is married with three children, wanted Cromartie to see firsthand what a settled home life was like.

"[Cromartie] didn't surround himself with caring and loving people, and I wanted him to see me and my family and realize I cared about him. I wanted him to see a family life," said Schwartz. "My intention was to show him that there are people who love you for who you are, not for how much you make. When I first met him, I saw a wonderful heart and human being that people were taking advantage of, and I wanted to be a part of seeing his personal growth. Part of that is financial discipline."

Cromartie grew extremely close to Schwartz's family -- the children now refer to him as "Uncle Antonio." And while he was there, Cromartie soaked in the financial lessons Schwartz imparted. He now applies them to his everyday life.

Schwartz set up a program where Cromartie's salary goes to his office, and Schwartz and his staff pay all the bills and put money into Cromartie's investments, all the while providing Cromartie with monthly reports to show where the money goes. The arrangement includes monthly child support payments for each of Cromartie's children, all of whom will be provided for through college. Cromartie remains active in the lives of all his children and he sees them regularly.

Schwartz, who also represents high-income earners in the music and entertainment industry, credits Cromartie with adjusting his lifestyle to suit his financial needs.

"I can tell a lot of things to a lot of clients, but that doesn't mean they'll listen and accept what I say and practice that discipline," Schwartz said. "[Cro] buys into it. He knows that a professional athlete's earning period is limited, and that the best form of accumulating wealth is not to spend. His peers will go buy Rolls Royces and Ferraris and diamond jewelry, but 25 years from now, Antonio can still maintain his lifestyle, sit at the beach enjoying a cocktail and say, 'I've earned it.'"

Schwartz said Cromartie's retirement is fully funded to age 100, and his wealth will be multi-generational, meaning his family will never have to worry about money.

Schwartz also acts as a shield in case friends or relatives come looking for money. Cromartie was reminded of that when Rams rookie wide receiver Tavon Austin recently said he was besieged by requests for money, even though he hasn't signed his first NFL contract.

"Everybody expects a lot of things from you as far as money," Austin said in an interview posted on the Rams' website. "My phone doesn't stop ringing now. It feels like they're counting my bank account now."

Cromartie can relate; the same thing happened to him early in his career. Not any more, though. He now refers all requests directly to Schwartz.

"I tell Cro, 'If a friend or family member to borrow money, have them call me,'" Schwartz said. "I'll often say, 'Antonio has good intentions. However, at this time, I've earmarked his money for other things and we don't have that readily available.' For the most part, they don't call back."

Cromartie can thank Schwartz for one more thing: introducing him to the Prius. Cromartie tooled around in Schwartz's Prius during the time he lived with his family.

Last Christmas, Cromartie's wife gave him the one he now drives.

But Cromartie will allow himself one indulgence with the new car.

"I'm gonna put some rims on it," he said. "That's about it, though."