Camp Wikoff helped put Montauk on the map

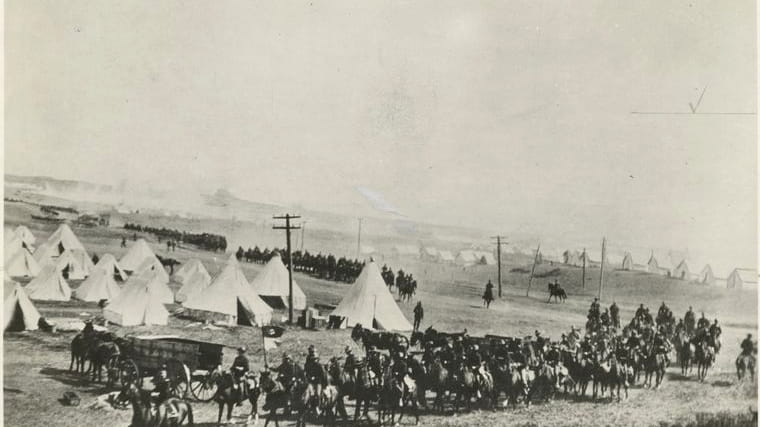

Camp Wikoff was only operational for two months in 1898 but it helped bring attention to the sleepy hamlet. Credit: NYPL

Aug. 15, 1898: An army is about to invade Montauk.

A little before 11 a.m. that morning, the troop transport ship Miami, anchored in Fort Pond Bay, lurched into motion. Led by a tugboat, the 3,050-ton vessel — its decks lined with soldiers — soon pulled alongside the recently constructed railroad pier that jutted into the bay.

The arrival of the Miami ignited a flurry of activity on shore, as hundreds of officials, laborers, newspaper reporters and spectators jostled for position near the pier, standing on wagons and railroad cars to get a better view. The presence of the crowd alone was unprecedented in the history of Montauk, a place that at the time had, by some estimates, no more than 50 full-time residents.

But the show had only just begun.

As the ship drew closer, festooned with regimental and American flags, the nearly 1,000 troops massed on her decks began to cheer. The crowd onshore responded in kind. But its cheers turned to roars when a bespectacled figure was discerned on the bridge, waving his hat.

“ ‘Roosevelt! Roosevelt!’ was the cry,” wrote a reporter from the New York Herald. “Hurrah for Teddy and the Rough Riders.”

Col. Theodore Roosevelt had arrived at Camp Wikoff.

Theodore Roosevelt, left, was among the thousands of returning soldiers who quarantined at Camp Wikoff. Credit: NYPL

By then, Roosevelt was a well-known figure, having resigned his post as assistant secretary of the Navy to fight in the short-lived Spanish-American War. Just six weeks earlier, T.R. and his Rough Riders had charged up a hill outside Santiago, Cuba, during the Battle of San Juan Hill — the decisive land battle in the four-month-long conflict to help liberate Cuba from Spain.

But few Americans had likely ever heard of Montauk. Far from being the popular summer resort area it is now, the eastern tip of Long Island was then remote and empty. Most of the Indigenous population had been forced off their land, and for more than 200 years Montauk had served as a pasture for the farmers of East Hampton, who grazed their sheep, cattle and horses on its grassy plains.

That was all about to change. The U.S. War Department had chosen the area as the site for a camp to house the Army’s 5th Corps returning from Cuba. About 22,500 men would ultimately be stationed at the camp, named for a senior officer killed a few weeks earlier in the fighting around Santiago. In addition to Roosevelt, President William McKinley would also visit the camp, with their movements along the visually stunning Montauk plains captured by newfangled movie cameras.

And in some ways, the camp provided the literal footprint for modern Montauk, according to historians. Some of the roads built for the 4,000-acre camp still remain, including what is now Edgemere Street and Flamingo Avenue, which lead from the area around the train station where the troops disembarked and up the hill to the quarantine hospital — now the site of Montauk Manor. In the decades after the Spanish-American War, some of these roads provided access to and around Montauk for those who began to venture out to this remote area in the early 20th century.

While the Long Island Rail Road’s Montauk station was built three years earlier, the additional tracks and buildings added by the LIRR during the two months the camp was operational would be used for years to come as railroad traffic increased.

Long Island Rail Road train depot in Montauk in 1898. Credit: Montauk Library Archives

“Montauk would have remained a remote area, used for grazing for many years, even decades, if Camp Wikoff had not been established there,” said historian and author Jeff Heatley, whose book “Bully! Colonel Theodore Roosevelt, the Rough Riders & Camp Wikoff” chronicles that brief but seminal period. (A revised edition was published in November 2023 by the East End Press and Montauk Historical Society.)

THE ‘MAN OF THE HOUR’

More than 125 years later, prowling the same beach where those returning soldiers disembarked, Heatley spots what he’s looking for.

“That’s it!” exclaims the bearded scholar, 78. As the waters of Fort Pond Bay glistened on a late February morning, Heatley pointed to what he believes are the faded indentations of a rail spur on Navy Road.

Following its footprint through the scrub brush and down to the beach, past a pile of concrete slabs, he gestured out to the bay. This, he believes, is where the iron pier was.

Concrete slabs near what is believed to be the site of the pier where soldiers from the Spanish-American War disembarked. Credit: Gordon M. Grant

And it is here where Roosevelt and his Rough Riders arrived in Montauk that day in 1898. The eyes of the country were riveted there not only because of the presence of the “Man of the Hour,” but because of what would become near-catastrophic conditions in the camp, as infectious diseases contracted in Cuba — malaria, typhoid, dysentery and a few cases of dreaded yellow fever — swept through the ranks. Camp officials were initially unprepared for the number of sick men. Anguishing scenes of gaunt, dying troopers (some even collapsed while on duty) are recounted in “Bully.” And as they were reported by the press, they enraged the nation.

Eventually, through the implementation of modern sanitary techniques, not to mention the efforts of the Red Cross, civilian volunteers from East Hampton and other East End communities, and Roosevelt himself (who got into a very public battle with the War Department over its mishandling of the camp), the situation was brought under control. But for 340 Americans (some of whom are buried in Cypress Hill Cemetery in Brooklyn), the idyllic dunes and waters of Montauk would be the last sights they saw on earth.

“More men died here than in the Battle of San Juan Hill,” Heatley said, referencing the U.S. death toll in the fight.

Historian and author Jeff Heatley poses in front of Third House, where Teddy Roosevelt stayed in Montauk. Credit: Gordon M. Grant

As he writes in “Bully,” New York City was then home to more than a dozen daily newspapers, with an estimated total circulation of almost 2 million readers in the late 1890s. Interest in Roosevelt, the returning troops and their struggle at Camp Wikoff was so intense that a separate encampment of reporters — a “Press Row” — sprang up near the railroad depot that had become the locus of activity at Camp Wikoff. In the days before newspapers could reproduce photographs, illustrators were there as well to capture the scenes visually.

“The story was so well-told by so many great reporters and illustrators,” Heatley said.

And yet today, this short-but-significant chapter in local history seems all but forgotten, said Heatley: “I think everybody on Long Island should know about Camp Wikoff.”

‘GOOD PLACE FOR A BASE’

Within a few years of the camp disbanding, a small fishing enclave had developed near the site of the base — although, like the buildings constructed for Camp Wikoff, it would vanish when a hurricane roared through in 1938.

With the arrival of Miami Beach developer Carl Fisher in the 1920s, the village now known as Montauk emerged on the plains south of the railroad station — where the expansive tent city of Camp Wikoff had stood and where McKinley addressed the troops in September 1898.

The influence of Camp Wikoff on the development of the modern community was, said Mia Certic, executive director of the Montauk Historical Society, “significant but subtle.”

“It put Montauk on the map, first and foremost,” she said. “All that intense national press attention was focused on a place that few had ever heard of before.”

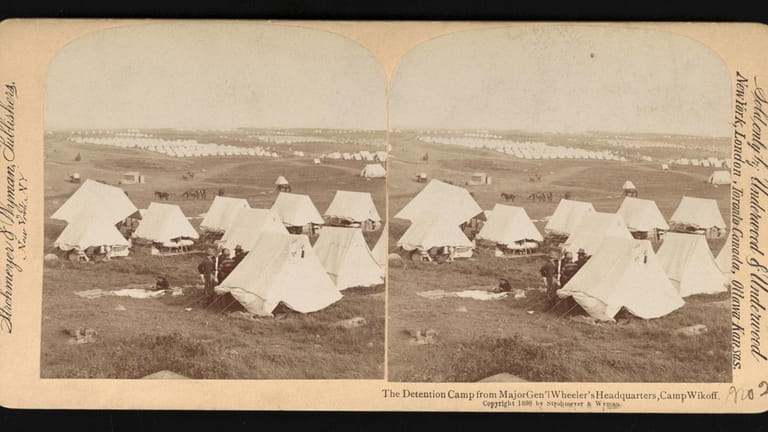

A stereoscopic image of Camp Wikoff, which held quarantined U.S. troops from Cuba. Credit: Library of Congress; P&P

Camp Wikoff, she noted, also led to a military presence in Montauk that lasted well into the late 20th century. “The Army and the Navy both seem to have thought, ‘Well, that’s a good place for a base,’ ” she said, pointing to the development in 1918 of a 30-acre World War I naval air base in Montauk (complete with hangars for dirigibles and seaplanes); and later Camp Hero, a coastal defense installation during World War II and subsequently an Air Force base. Camp Hero is now a state park, and its Cold War-era radar tower remains a striking feature of the Montauk landscape. “So there is a tradition of a military presence in Montauk that can be traced back to Camp Wikoff,” Certic said.

Camp Wikoff is important in another way: “It was the passing of the torch into the 20th century,” said Brian Tadler, a historical educator at Sagamore Hill National Historic Site in Cove Neck. “This was Roosevelt in the ascendancy, and America as well.”

TECHNOLOGICAL MARVELS

Indeed, a new world was springing up in Montauk in 1898, filled with modern technological marvels. The railroad station was reportedly abuzz with the sounds of telephones ringing. A Tesla generator provided electric lights for the camp. And some of the earliest documentary films were taken there. One of them shows the sweep of the camp — thousands of tents stretched out along what is now Montauk Village and Ditch Plains — taken around the time the camp had another special visitor: President McKinley, who on Sept. 4, 1898, spoke to 5,000 troops assembled on a field near what is now Montauk’s Village Green. (It would be McKinley’s assassination in 1901 that made Roosevelt, by then vice president, the 26th president of the United States.)

Yet, while Camp Hero is well known, Camp Wikoff — and all of the boldface names who intersected with it — is virtually forgotten.

“It’s really a shame how little there is to commemorate it,” Heatley said. The name of the Rough Riders Landing condo development on Fort Pond Bay provides a hint of what once happened there; a few plaques scattered around Montauk tell, to various degrees of depth, the story of the camp. Yet, one of those memorials to Camp Wikoff is barely discernible, planted in the grass along the outside of a local Little League ballfield.

“As my old English professor would say, ‘A sad commentary,’ ” Heatley observed.

The Village Green in Montauk. President William McKinley once spoke to a group of thousands of soldiers here while they were quarantined. Credit: Gordon M. Grant

While there was a flurry of activity during the camp’s centennial in 1998, both Heatley and the Montauk Historical Society have plans to try again to raise its ghostly profile. Visitors to Montauk Lighthouse, for example, can now have an Augmented Reality version of Roosevelt guide them through the history of Montauk, including the camp, via an app that allows a virtual T.R. to appear on their phone and relate his experiences in the hamlet.

Heatley is also working on a historical bike tour of the sprawling camp, including a climb up the hill to the site of the camp’s quarantine hospital.

Certic hopes to increase historical signage and expand the use of augmented reality technology to link some or all of the stops on Heatley’s proposed bike tour to the society’s website.

But it will take time to restore the memory of a place that, even at the time it was abandoned, was the subject of speculation and mixed emotions on the East End.

On Oct. 29, 1898, E.S. Broughton, then the editor of the East Hampton Star, visited Montauk, and wrote a poignant observation that Heatley includes in “Bully.”

“There is a weird gloom about the place from which one cannot escape,” he mused. “From the tops of the hills one can look on sea and sound and imagine Montauk to be what it was before the invasion by the army.”

Broughton was moved by the cluster of buildings around the railroad station “boarded up and left as sad reminders of the scenes of pleasure, joy, delight, sadness, sorrow and misery which were alternately presented there during the existence of Camp Wikoff.”

The fact that it did exist is what Heatley, as well as many in the local historical community, would like everyone to know.