Irish independence leader, onetime Manorville farm owner, to be remembered for heroism at 'Mass rock' ceremony

AOH Suffolk County president Bill Corrigan, left, and historian Mike McCormack at the Thomas James Clarke and Kathleen Daly Clarke obelisk in Manorville on Thursday. Credit: Morgan Campbell

He was one of the key leaders of the 1916 “Easter Rising” armed insurrection that ended with his execution but paved the way for most of Ireland to win its independence from Britain.

But before that, Thomas James Clarke lived on Long Island. For nearly two years, he and his wife, Kathleen, lived on a 60-acre farm they bought in Manorville.

As St. Patrick’s Day arrives, some Irish Americans are remembering the heroism of a one-time Suffolk resident who became a legendary revolutionary in Ireland.

“Thomas James Clarke was the Sam Adams of Ireland,” said Mike McCormack, the New York State historian and former national historian for the Ancient Order of Hibernians, referring to one of the leaders of the American Revolution. “He was the guy behind the revolution of 1916.”

At the site of Clarke’s former farm, the Hibernians have erected a monument honoring him and his wife, Kathleen Daly Clarke, a noted leader of the Irish independence movement herself.

McCormack and others had heard a rumor of the Clarkes’ move to Suffolk County, and spent three years researching to confirm it. They finally did in the 1980s, finding deeds to two 30-acre adjoining properties in Manorville with Thomas Clarke’s name on them.

McCormack lobbied politicians to declare the site a historic landmark, and the Town of Brookhaven soon did. To mark the location and honor Clarke and his wife, the Hibernians erected a two-ton Wicklow granite obelisk carved and engraved in Ireland.

Eighteen months ago, they added a “Mass Rock” — a flat-topped stone of the same type the Irish used as altars when they celebrated Roman Catholic Masses in secret in the woods because of British persecution.

Next month, after Easter and the 108th anniversary of the uprising, the Hibernians will hold their annual wreath laying ceremony at the rock to remember the martyred Clarke and his wife.

Thomas Clarke, who was naturalized during his time in New York, was the only American citizen executed by the British for the Easter Rising.

His story — and the role of the Roman Catholic Church in Ireland — is attracting the interest of such people as Bishop John Barres of the Diocese of Rockville Centre and Cardinal Timothy Dolan of New York.

Whenever Dolan visits Ireland, including last August, “I always look forward to having the opportunity to celebrate Mass at one of the ‘Mass Rocks’ that dot the country,” he said in a statement. “It never fails to remind me that in times of trouble and persecution, people turned to the rock of their faith for strength and comfort.”

He said he hopes to visit the Manorville site soon, and perhaps even celebrate Mass there.

Clarke’s path to Long Island started with the 15 years he spent in British prisons, where he was tortured and nearly starved for his activities in the Irish independence movement, McCormack said.

By 1900, like many Irish revolutionaries, he moved to New York to escape persecution by the British and to help raise funds for the cause of Irish independence.

Kathleen, whom he had earlier met in Ireland, where they fell in love, soon followed him. She was from a revolutionary family also — her uncle had served time in prison with Thomas.

The two married in New York in 1901, and lived in the Bronx and Brooklyn before moving to Manorville in early 1906 with their children for health reasons, said McCormack, who lives in Selden. Kathleen may have had an asthmatic condition, he said.

On the farm, Thomas Clarke grew vegetables that he sold locally, and cut down trees that he sent to New York City for use in fireplaces, McCormack said.

Clarke sensed that a world war was coming, and Britain might be involved and distracted — a good time to relaunch the independence movement, McCormack said.

So he and his family moved back in November 1907.

He opened a tobacco shop in Dublin, but surreptitiously gave out orders as he helped rebuild the nationalist movement.

They planned a major rebellion for Easter Sunday 1916. The idea was to take over British-run government buildings in Dublin — including the central post office — and other strategic points to spark the masses to rise up and overthrow the British, said Alan Singer, a professor of education at Hofstra University and a historian who co-authored a curriculum about Ireland.

The plot had to be aborted for Easter when one leader got nervous about its prospects for success and publicly called off the “maneuvers.” But Clarke pushed on, and launched it the next day — April 24, 1916 — with a few thousand followers.

He and other leaders took over several buildings, with the post office serving as their headquarters. For nearly a week, they exchanged fire with the British, until they were finally overwhelmed by British artillery. With some badly injured, the 2,500 patriots surrendered to 20,000 British troops.

The masses never rose up, partly because the British had shut down all media including radio, newspapers and telegraphs. The rest of the country did not learn about the rebellion until it was over. The insurrection seemed like a failure.

But then the British made a major miscalculation: Without any legal representation or due process, they lined up Clarke and 13 other leaders before a firing squad in a jail.

The Irish public was outraged, Singer said.

“The assassination of the participants infuriated the Irish population and turned the population from tacit acceptance of British rule to a commitment to overturning British colonialism in Ireland,” he said.

McCormack said the uprising “really turned out to be the Bunker Hill of Irish military history because the reaction of the British … was in the extreme.”

With her husband dead, Kathleen Clarke became an even more integral part of the independence movement, working with Michael Collins, the new head of the resistance. The Irish Republican Army was born, and waged a guerrilla war against the British, forcing them to the treaty table.

By 1921 Britain allowed most of Ireland to become a “free state” — a self-governing dominion that still required British approval for international affairs.

By 1949, the free state became its own fully independent Republic of Ireland. Six counties in Northern Ireland remained under British control and were plagued by conflict that did not end until 1998.

Kathleen Clarke went on to become a delegate to the Irish parliament and the first woman mayor in Irish history, presiding over Dublin. In 1972 she received the rare honor of a state funeral in Ireland when she died at age 94.

Over the decades, the Easter Rising her husband helped lead has been immortalized by figures including the Irish poet William Butler Yeats, who wrote “Easter, 1916.”

McCormack said he hopes more Long Islanders and others of Irish descent will pay tribute to Clarke on St. Patrick's Day. Clarke “was a military genius,” he said, “the dedicated Irish patriot who put a British colony on the road to the independent Republic of Ireland.”

He was one of the key leaders of the 1916 “Easter Rising” armed insurrection that ended with his execution but paved the way for most of Ireland to win its independence from Britain.

But before that, Thomas James Clarke lived on Long Island. For nearly two years, he and his wife, Kathleen, lived on a 60-acre farm they bought in Manorville.

As St. Patrick’s Day arrives, some Irish Americans are remembering the heroism of a one-time Suffolk resident who became a legendary revolutionary in Ireland.

“Thomas James Clarke was the Sam Adams of Ireland,” said Mike McCormack, the New York State historian and former national historian for the Ancient Order of Hibernians, referring to one of the leaders of the American Revolution. “He was the guy behind the revolution of 1916.”

WHAT TO KNOW

- A key leader of the 1916 “Easter Rising” rebellion, which helped lead to the independence of Ireland from Britain, once lived on Long Island.

- Thomas James Clarke bought a 60-acre farm in Manorville and lived there for two years with his wife and children before returning to Ireland to launch the insurrection that changed Irish history.

- Irish Americans are paying tribute to him as St. Patrick's Day approaches, and hoping more people learn about his Long Island connection.

Clarke's Long Island connections

At the site of Clarke’s former farm, the Hibernians have erected a monument honoring him and his wife, Kathleen Daly Clarke, a noted leader of the Irish independence movement herself.

McCormack and others had heard a rumor of the Clarkes’ move to Suffolk County, and spent three years researching to confirm it. They finally did in the 1980s, finding deeds to two 30-acre adjoining properties in Manorville with Thomas Clarke’s name on them.

McCormack lobbied politicians to declare the site a historic landmark, and the Town of Brookhaven soon did. To mark the location and honor Clarke and his wife, the Hibernians erected a two-ton Wicklow granite obelisk carved and engraved in Ireland.

Eighteen months ago, they added a “Mass Rock” — a flat-topped stone of the same type the Irish used as altars when they celebrated Roman Catholic Masses in secret in the woods because of British persecution.

Next month, after Easter and the 108th anniversary of the uprising, the Hibernians will hold their annual wreath laying ceremony at the rock to remember the martyred Clarke and his wife.

Thomas Clarke, who was naturalized during his time in New York, was the only American citizen executed by the British for the Easter Rising.

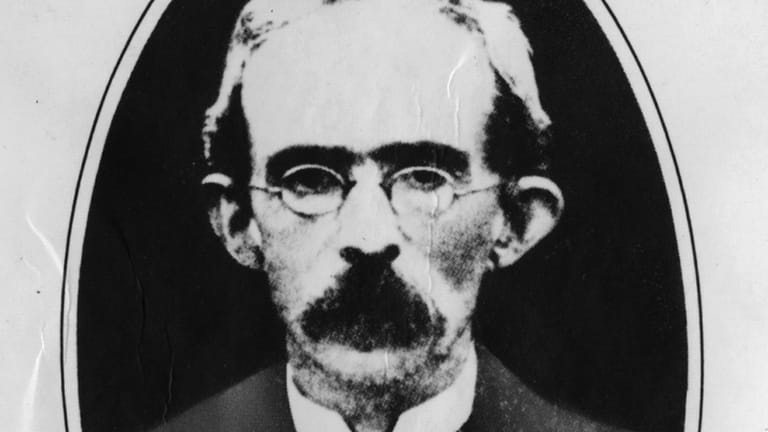

An undated photo of Thomas Clarke. Credit: Newsday File Photo

His story — and the role of the Roman Catholic Church in Ireland — is attracting the interest of such people as Bishop John Barres of the Diocese of Rockville Centre and Cardinal Timothy Dolan of New York.

Whenever Dolan visits Ireland, including last August, “I always look forward to having the opportunity to celebrate Mass at one of the ‘Mass Rocks’ that dot the country,” he said in a statement. “It never fails to remind me that in times of trouble and persecution, people turned to the rock of their faith for strength and comfort.”

He said he hopes to visit the Manorville site soon, and perhaps even celebrate Mass there.

Planting seeds of the Irish revolution

Clarke’s path to Long Island started with the 15 years he spent in British prisons, where he was tortured and nearly starved for his activities in the Irish independence movement, McCormack said.

By 1900, like many Irish revolutionaries, he moved to New York to escape persecution by the British and to help raise funds for the cause of Irish independence.

Kathleen, whom he had earlier met in Ireland, where they fell in love, soon followed him. She was from a revolutionary family also — her uncle had served time in prison with Thomas.

The two married in New York in 1901, and lived in the Bronx and Brooklyn before moving to Manorville in early 1906 with their children for health reasons, said McCormack, who lives in Selden. Kathleen may have had an asthmatic condition, he said.

The former home of Thomas James Clarke and his wife, Kathleen Daly Clarke, on Chapman Boulevard in Manorville in February 1986. Credit: Newsday Photo/Jim Peppler

On the farm, Thomas Clarke grew vegetables that he sold locally, and cut down trees that he sent to New York City for use in fireplaces, McCormack said.

Clarke sensed that a world war was coming, and Britain might be involved and distracted — a good time to relaunch the independence movement, McCormack said.

So he and his family moved back in November 1907.

He opened a tobacco shop in Dublin, but surreptitiously gave out orders as he helped rebuild the nationalist movement.

They planned a major rebellion for Easter Sunday 1916. The idea was to take over British-run government buildings in Dublin — including the central post office — and other strategic points to spark the masses to rise up and overthrow the British, said Alan Singer, a professor of education at Hofstra University and a historian who co-authored a curriculum about Ireland.

The plot had to be aborted for Easter when one leader got nervous about its prospects for success and publicly called off the “maneuvers.” But Clarke pushed on, and launched it the next day — April 24, 1916 — with a few thousand followers.

He and other leaders took over several buildings, with the post office serving as their headquarters. For nearly a week, they exchanged fire with the British, until they were finally overwhelmed by British artillery. With some badly injured, the 2,500 patriots surrendered to 20,000 British troops.

The masses never rose up, partly because the British had shut down all media including radio, newspapers and telegraphs. The rest of the country did not learn about the rebellion until it was over. The insurrection seemed like a failure.

But then the British made a major miscalculation: Without any legal representation or due process, they lined up Clarke and 13 other leaders before a firing squad in a jail.

The Irish public was outraged, Singer said.

“The assassination of the participants infuriated the Irish population and turned the population from tacit acceptance of British rule to a commitment to overturning British colonialism in Ireland,” he said.

McCormack said the uprising “really turned out to be the Bunker Hill of Irish military history because the reaction of the British … was in the extreme.”

Kathleen Clarke picks up the revolution mantle

With her husband dead, Kathleen Clarke became an even more integral part of the independence movement, working with Michael Collins, the new head of the resistance. The Irish Republican Army was born, and waged a guerrilla war against the British, forcing them to the treaty table.

By 1921 Britain allowed most of Ireland to become a “free state” — a self-governing dominion that still required British approval for international affairs.

By 1949, the free state became its own fully independent Republic of Ireland. Six counties in Northern Ireland remained under British control and were plagued by conflict that did not end until 1998.

Kathleen Clarke went on to become a delegate to the Irish parliament and the first woman mayor in Irish history, presiding over Dublin. In 1972 she received the rare honor of a state funeral in Ireland when she died at age 94.

Over the decades, the Easter Rising her husband helped lead has been immortalized by figures including the Irish poet William Butler Yeats, who wrote “Easter, 1916.”

McCormack said he hopes more Long Islanders and others of Irish descent will pay tribute to Clarke on St. Patrick's Day. Clarke “was a military genius,” he said, “the dedicated Irish patriot who put a British colony on the road to the independent Republic of Ireland.”