NY, LI need more overdose prevention centers

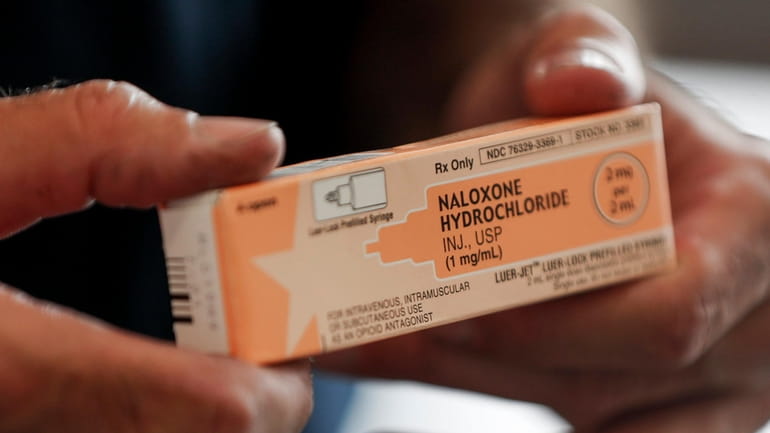

Naloxone, a lifesaving medication that reverses opioid overdoses, is carried at all overdose prevention centers. Credit: AP/Keith Srakocic

Every 90 minutes, a New Yorker dies from a preventable drug overdose. Long Island, too, has been ravaged; Nassau and Suffolk counties have two of the 10 highest overdose death rates in New York State. Drug overdoses have become the leading cause of death for New Yorkers under 50, with mortality rates skyrocketing over the past decade — from 8 to 30 deaths per 100,000 people. As the crisis escalates, we must turn to proven solutions: overdose prevention centers, or OPCs.

In the U.S., the first two legally sanctioned OPCs opened in 2021 in East Harlem and Washington Heights, under the nonprofit OnPoint. They reversed 1,300 overdoses in their first year. Three years later, these two centers remain the only OPCs in New York. None have been proposed on Long Island despite the need.

Overdose prevention centers provide a safe space for people struggling with addiction. They can use drugs in a supervised and hygienic environment, access health and social services, find supportive community, and make progress toward recovery. We understand there is often significant community resistance to these centers, but decades of research on OPCs in more than 50 countries has affirmed their efficacy — not only do they reduce overdose deaths, they also reduce disease transmission, public drug use, syringe litter, and drug-related crime, while expanding access to treatment. Naloxone, a lifesaving medication that reverses opioid overdoses and is carried at all OPCs, keeps participants safe and gives them another chance to enter treatment. Not a single person has died at a center, numerous studies have found.

Overdoses consistently rank in the top 15 causes for emergency room admissions. As medical students, we’ve witnessed firsthand the inadequacies of our emergency medical infrastructure in addressing substance use disorders. Our ERs are flooded. We’ve seen patients waiting up to eight hours — and the same patients returning to the ER weeks later because they were discharged to the same conditions that led to their initial overdose with no follow-up care. OPCs provide more comprehensive support and reduce ER strain; OPCs have been shown to reduce ambulance calls for overdoses by up to 67%.

This guest essay reflects the views of Aidan Pillard and Mia Pattillo, medical students at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and Weill Cornell Medical College in Manhattan.

Our experiences volunteering at OnPoint’s OPCs have shown us a compelling vision of what effective support for those battling addiction should involve. People find respite from the streets to shower, wash their clothes, eat a snack, and use their drugs in a safe environment. OPCs serve as gateways to physical and behavioral health services, social services, and job opportunities. The trust between staff and participants catalyzes transformations; some participants begin addiction treatment and others staff the center themselves.

Some critics argue that OPCs increase crime and nuisance conditions in surrounding neighborhoods. But data from the two existing OPCs paints a different picture: Rates of theft, low-level drug enforcement, and police narcotics activity have all decreased. Moreover, staff engage actively with the community and solicit feedback from neighbors.

Another misconception is that OPCs condone drug use. This argument echoes past objections to harm reduction measures, such as syringe service programs introduced amid the HIV/AIDS epidemic or condom distribution on college campuses — both of which are now highly successful and widely adopted. Providing safe spaces for drug use does not serve to promote it; instead, it minimizes risk.

OPCs treat clients with dignity, save lives, and advance public health and safety. New York must expand OPCs on Long Island and elsewhere and lead the country in combating the overdose crisis.

This guest essay reflects the views of Aidan Pillard and Mia Pattillo, medical students at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and Weill Cornell Medical College in Manhattan.