‘The Future Is History’ review: Journalist Masha Gessen looks at life for ordinary Russians under Putin

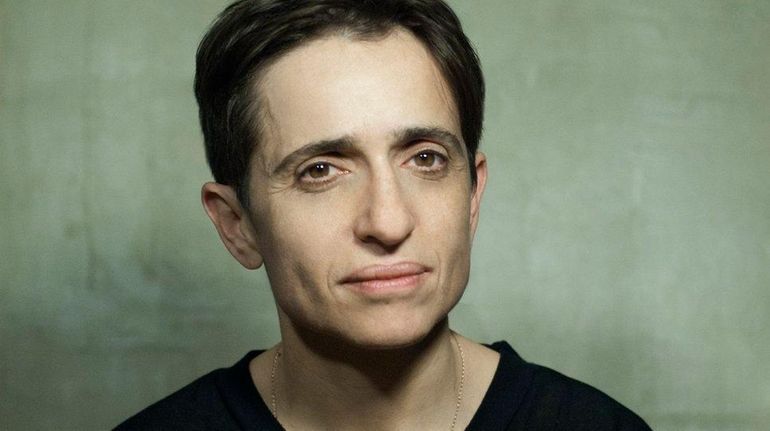

Masha Gessen, author of "The Future Is History." Credit: Tanya Sazansky

THE FUTURE IS HISTORY: How Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia, by Masha Gessen. Riverhead, 515 pp., $28.

Something about the story of Russia’s meddling in the 2016 presidential election muddles the brain — it’s diffuse, creepy and hard to understand. And the probes into Russian contacts with several of Donald Trump’s advisers have a whack-a-mole quality. Who’s complicit? Who’s guilty? And what is Russia’s game?

Readers of “The Future Is History,” Masha Gessen’s brilliant and sobering new book about totalitarianism’s takeover of contemporary Russia, will get some scary perspective on these questions — her immersion into Russia’s three decades of decline since perestroika is a plunge into the deep end of a very cold pool. A Russian journalist now living in America, Gessen builds the case that Vladimir Putin, Russia’s de facto dictator, regards America as Russia’s mortal enemy, and most Russians go along with him. Buffeted by old animosities, new propaganda and timeless envy, Russians see the United States as “the country that Russia had failed to become. . . . attractive and threatening at the same time, worth emulating and eminently hateable,” Gessen writes.

Only 25¢ for 5 months

Something about the story of Russia’s meddling in the 2016 presidential election muddles the brain — it’s diffuse, creepy and hard to understand. And the probes into Russian contacts with several of Donald Trump’s advisers have a whack-a-mole quality. Who’s complicit? Who’s guilty? And what is Russia’s game?

Readers of “The Future Is History,” Masha Gessen’s brilliant and sobering new book about totalitarianism’s takeover of contemporary Russia, will get some scary perspective on these questions — her immersion into Russia’s three decades of decline since perestroika is a plunge into the deep end of a very cold pool. A Russian journalist now living in America, Gessen builds the case that Vladimir Putin, Russia’s de facto dictator, regards America as Russia’s mortal enemy, and most Russians go along with him. Buffeted by old animosities, new propaganda and timeless envy, Russians see the United States as “the country that Russia had failed to become. . . . attractive and threatening at the same time, worth emulating and eminently hateable,” Gessen writes.

Gessen is an authoritative Russia hand in part because she is Russian herself. She left the country after authorities began to discuss taking children away from gay parents (she is gay). Author of several books, including a biography of Putin, she writes that the story of Putin’s reign has been told before, but she aims for something more: “I also wanted to tell about what did not happen: the story of freedom that was not embraced and democracy that was not desired.”

Writing in fluent English, with formidable powers of synthesis and a mordant wit, Gessen follows the misfortunes of four Russians who have lived most of their lives under Putin: Lyosha, the gay academic; Masha, activist and journalist (not the author); Seryozha, a child of the Russian elite; and Zhanna, daughter of Boris Nemtsov, an anti-Putin politician.

Gessen interweaves other stories as well; especially enlightening is the research of Lev Gudkov, a sociologist who has studied Russian public opinion throughout the Putin era. Gudkov has documented a vein of deep longing for stability in the Russian people, so pervasive that they will accept almost anything to preserve it.

Putin’s assaults against a free society are shocking, in part because most Russians tolerate and support him. He has almost completely eliminated directly elected posts in the vast governmental empire. He controls judicial appointments. He directs sham elections for the few such positions that remain. He has seized control of major businesses and industries, and business leaders who opposed him have been stripped of their wealth, sometimes jailed and in select cases murdered.

More troubling is the emergence of a fierce Russian nationalist vision, with broad public enthusiasm for plans to retake any country with a major population of ethnic Russians. Most disturbing: the sanctioned harassment and visceral hate of those who are different, especially Russian gays, who have been harassed, beaten, tortured and murdered.

Gessen fears that Russian society is dying under Putin — even life expectancy is shorter than in many developing countries. It’s hard to imagine how any creativity, originality or innovation can survive such a societal straitjacket.

And yet — perhaps most amazing is the resilience of the Russian resistance. Harassed, jailed, beaten, murdered — Russians still march against and protest the outrages of Putin’s regime. Will they prevail? Hard to say. One of Gessen’s subjects, a Russian psychoanalyst, concluded that, “This country wanted to kill itself. Everything that was alive here — the people, their words, their protest, their love — drew aggression because the energy of life had become unbearable for this society.” Gessen vividly chronicles the story of a mortal struggle.