Dispatches from Alaska: On the front lines of climate change

An Arctic ground squirrel caught by a research team investigating how these hibernating rodents—which provide food for everything from eagles to wolves—respond as temperatures in the Arctic warm. (Aug. 3, 2011) Credit: Newsday / Jennifer Smith

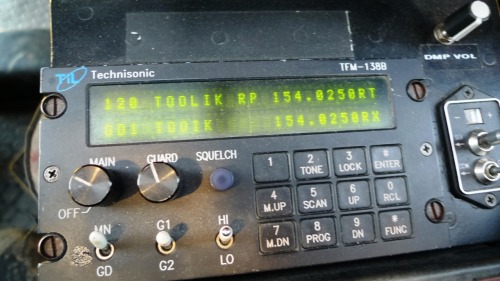

Newsday environmental reporter Jennifer Smith filed dispatches from Alaska during the two weeks she joined climate change scientists at the remote Arctic Long Term Ecological Research station at Toolik Lake. As part of Smith's fellowship with the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Mass., she worked alongside researchers studying how global warming affects plants and animals and the Earth’s capacity to absorb greenhouse gases.

You can also follow Jennifer on Twitter: @smithjenBK

Only 25¢ for 5 months

Newsday environmental reporter Jennifer Smith filed dispatches from Alaska during the two weeks she joined climate change scientists at the remote Arctic Long Term Ecological Research station at Toolik Lake. As part of Smith's fellowship with the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Mass., she worked alongside researchers studying how global warming affects plants and animals and the Earth’s capacity to absorb greenhouse gases.

You can also follow Jennifer on Twitter: @smithjenBK

Saturday, Aug. 6

Toolik Lake post-script: New York is a hot, crowded world away from the tundra and the Brooks Range, but I can revisit the North Slope (and some charismatic megafauna), thanks to this video of some fox kits and a wolf seen near the Arctic Long Term Ecological Research site.

Both critters were the talk of the Toolik field camp during my stay, but I wasn’t lucky enough to see them myself.

The video was shot and edited by staff naturalist Seth Beaudreault, another one of the dauntingly adventurous “bipolar” types I met there who hops between gigs in the Arctic and Antarctica. Many thanks to Seth for sending this my way!

Thursday, Aug. 4

About to leave Anchorage, and sorry to say goodbye to a most singular state. Good thing I have souvenirs from the Deadhorse supply store! Dalton Highway long-sleeve tee, complete with silk-screened musk ox (I did, finally, see one in the flesh on the drive from Toolik to Prudhoe Bay).

One of the three infamous Toolik Towers, i.e. outhouses, that serve the camp. Did I mention there was no wastewater disposal system here?

Thursday, Aug. 4

Last sunset (for me) over Toolik Lake.

Thursday, Aug. 4

Thursday, Aug. 4

The view on a clear morning.

Toolik Lake.

Thursday, Aug. 4

View from the dining hall, aka, my office.

Thursday, Aug. 4

The sauna. It’s not quite the luxury it seems—there’s no wastewater disposal system here at Toolik, so showers are rationed at two per week. To get clean, and to unwind after an exhausting day of field work or lab chores, researchers warm up around a wood-burning stove, then dive into the cool waters of Toolik Lake before scrubbing off on the deck. Not quite the same as a shower, but marvelous in its own right.

Thursday, Aug. 4

Buckets of tundra from “the pluck.”

Still life with tent lab.

Thursday, Aug. 4

A ground squirrel (aka as a Sik Sik) on the run.

The Sik Sik Sub.

Thursday, Aug. 4

The lovely ladies of Toolik.

Wednesday, Aug. 3

Well, after 11 days at the Arctic Long Term Ecological Research site, it’s time to say goodbye to Toolik Lake.

It's been an extraordinary experience. The landscape is like none I’ve seen, and the volume and complexity of the science undertaken here is fairly staggering to a layperson like myself. Thankfully most of the researchers have been very patient!

Herewith, a visual list of the things I will miss about this very special place, concluding with one thing I won’t.

Wednesday, Aug. 3

University of Alaska doctoral student Melanie Richter preps for squirrel surgery.

The animals are put under, then weighed, and blood samples are taken.

A female squirrel fitted with a temperature sensor recovers from surgery.

Wednesday, Aug. 3

On Wednesday I rejoined Team Squirrel, this time in the lab as they continued their work tracking the fitness and hibernation timing of Arctic ground squirrels as the region warms.

The science team from University of Alaska’s Institute of Arctic Biology had been out that morning trapping more squirrels. These ones were bound for the field station.

Researchers Melanie Richter and Cory Williams were in charge of the de-facto veterinary office. At one end of the lab the ground squirrels made their unhappiness known with a running cascade of cage-rattling chirps and growls. By the window, Richter and Williams prepped the rodents.

One by one, each squirrel was put under. It’s a two-step process: first the squirrel gets put in a large pickle jar connected to an anesthesia dispenser. Once knocked out, the rodent is removed and laid out on a table. More anesthesia piped through a cone over the squirrel’s head ensures it stays under, and a painkiller is injected.

The researchers took blood samples from each squirrel, then handled them gently to make sure they got through it okay.

A female had more in store for her. She was fitted with a microchip tracker—the same type you’d use on your dog or cat—and then prepped for surgery.

A temperature logger about the size and shape of a Mento was inserted in her abdomen. The device will help the University of Alaska researchers remotely monitor when she goes into hibernation, when she wakes up, and when she gives birth.

Tuesday, Aug. 2

A female wolf spider, the species that is the focus of Duke researcher Amanda Koltz’s work here at Toolik.

She’s set up lab versions of the tundra to track the spiders’ movements under different conditions. Koltz wants to know if warming will cause the spiders to spend more time above or below-ground, choices that could alter their diet and potentially affect how quickly carbon in the leaf litter is returned to the atmosphere.

Highlighter on the spider’s abdomen shows up under black light.

Monday, Aug. 1

Research assistant Samantha Walker, an undergraduate zoology student at North Carolina State University in Raleigh, inspects spider traps at experimental plots maintained by Duke University researcher Amanda Koltz.

Koltz shows how the trap works. Spiders crawl in, then a funnel deposits them on the bottom of the container.

Monday, Aug. 1

Tuesday was another rainy day at the Arctic Long Term Ecological Research site. Luckily Amanda Koltz, a doctoral student in ecology at Duke University, didn’t have to walk too far to inspect her experimental plots on the hill overlooking Toolik Lake.

Koltz is studying how climate change may affect wolf spiders, excellent hunters that live in a variety of habitats ranging from the Arctic to Arizona. She’s particularly interested in their role here on the tundra, where these predators connect the food web on surface of the land with that occupying the soil below.

Over the past 15 years in Greenland, scientists have observed spiders getting bigger as the growing season extended due to higher average temperatures, Koltz said. And female spiders’ growth outpaced that of the males.

“The bigger the female, the bigger their egg sacs and the more eggs they can carry,” Koltz said. “If there was a big change in spider density or body size, that could have an affect on the birds… Different types of spiders can have a huge impact on the plant and insect community.”

Mosquitoes buzzed around Koltz as she and a graduate student checked spider traps in one section of her plots. Some plots are enclosed with metal fencing, others with tilted plastic borders that simulate the warming effects of climate change. Some plots have no spiders, others have many.

The idea is to measure how the absence or presence of spiders affects the other invertebrates there, which could affect how the soil stores and releases carbon from decaying plant matter.

“In the Arctic, so much carbon is stored in the active layer of the soil,” Koltz said back at her lab. “It’s dead plants that haven’t decomposed yet.”

If the bacteria and fungi that eat the organic matter speed up as temperatures warm, or increase their numbers, that could release carbon more quickly back into the atmosphere through the process scientists call respiration. Just as we exhale carbon dioxide, so do the organisms in the soil.

“It’s just all the animals breathing—below ground,” she said.

Monday, Aug. 1

Thermokarst erosion caused by thawing permafrost has exposed the brown mineral seen here.

Penn State hydrogeologist Michael Gooseff and doctoral candidate Allison Truhlar measure out the distance where they will lay wires to connect the white soil moisture wells with a device to record the data.

A modified cooler containing a data logger like the once they plan to install at this site near the Toolik River thermokarst.

Monday, Aug. 1

Scientist Michael Gooseff of Penn State and doctoral candidate Allison Truhlar (a Stony Brook native!) walk toward an experiment site near the Toolik River thermokarst. Typically tundra streams are bordered by shrubby willow. But here the permafrost that undergirds the tundra has thawed, causing the tussocks to tumble down toward the water. Yellow research flags mark points of study.

Gooseff inspects a ground temperature station, which contains three separate loggers to track how warm or cool the soil gets.

Clad in “bug jackets” to ward off the swarms of mosquitoes on the tundra that night, Gooseff and Trulahr examine a modified cooler that contains a data logger. All the information collected from the soil moisture wells and temperature monitoring equipment feeds into the logger via brown wires encased in white PVC pipes. The PVC is to prevent Arctic ground squirrels from chewing through the wires.

Monday, Aug. 1

Toolik Lake, Day 8 (the night shift)

The thing about the Arctic summer is that it’s light almost 24 hours a day here. So scientists at Toolik cram as much fieldwork as they can into their limited time at the field station.

On Monday—after a full day trapping squirrels down by the Atigun River—I hopped in a truck with Penn State associate professor Michael Gooseff to check out an example of what happens when Arctic permafrost begins to thaw.

Our destination: the Toolik River thermokarst, about 10 miles north of the Toolik Lake field station. A thermokarst is the uneven ground that results when the frozen soil that lies beneath the tundra’s springy layer of decaying organic material thaws. Meltwater moves through the ground, which slumps and collapses. It’s something that hydrogeologists such as Gooseff who track such events think is happening more often as the Arctic warms.

“In the 1980s, 17 of these were not around,” he said, as we walked out toward the site where he and Allison Truhlar, a doctoral candidate originally from Stony Brook, planned to install additional monitoring equipment.

Scientists at the Toolik field station are paying close attention to thermokarsts, hoping to determine what they mean for the tundra’s ability to sequester carbon, and for the health of stream and river systems nearby.

Gooseff and his colleague, Breck Bowden, a professor with the University of Vermont, discovered this particular thermokarst in 2003, during a helicopter flight when they noticed the Toolik River seemed awfully brown. Eventually they found that a large swath of permafrost had failed beneath a tributary of the river.

The thermokarst opened up a chasm in the tundra and created a waterfall with a drop of more than six feet, Gooseff said.

They’ve been studying the area ever since. His goal: “to figure out if Arctic stream networks are expanding because of permafrost degradation due to climate change.”

Eight years later, the Toolik River thermokarst has changed the shape of the tundra. Usually streams in this area are lined with willows or other shrubs. But here the tussocks of the tundra have literally tumbled down a slope, exposing mud flats of bare mineral soil.

Research teams have set out temperature loggers to track how warm or cold the soil gets. They’ve also installed wells to monitor soil moisture. They’ve done this at three plots: a hill slope, an area near what he calls a “water track” and right next to the thermokarst.

“These in concert are measuring the amount of heat and water and when they happen together,” Gooseff said.

Monday, Aug. 1

They mostly scooted too quick to catch on video, but these are the holes where ground squirrels live when they’re not being lured into cages by scientists.

Monday, Aug. 1

They commute by river, and this is their office. On a windy day with no mosquitoes, Team Squirrel have it pretty good.

Monday, Aug. 1

Tools of the trade.

Once trapped, the ground squirrel is weighed and measured.

Those caught for the first time are tagged.

After releasing the squirrel, University of Alaska scientist Michael Sheriff scoops up its poop for analysis later to determine what the squirrel has been eating.

Monday, Aug. 1

Catch and release, ground squirrel style. University of Alaska researcher Michael Sheriff places a specially-made bag over one end of the cage, then prods the squirrel in. Once inside the mesh portion, the wriggling rodent can be weighed, measured and processed without causing undue injury to either party.

Monday, Aug. 1

Monday, Aug. 1

University of Alaska scientist Michael Sheriff gives an in-the-field checkup to an Arctic ground squirrel lured into a trap at by fresh carrots.

Sheriff’s research team is investigating how these hibernating rodents—which provide food for everything from eagles to wolves—respond as temperature in the Arctic warm.

One way to do that is to monitor their overall fitness. Here Sheriff weighs and measures the angry rodent before letting it scamper off across the tundra at one of his research plots at Atigun Gorge, in the shadow of the Brooks range on Alaska’s North Slope.

Monday, Aug. 1

University of Alaska scientist Michael Sheriff (R) and his research assistant, Brady Salli head for Atigun Gorge to trap ground squirrels. They’re investigating how these rodents respond to climate change. The trip involves a hike along the Atigun River and a short hop across the water to reach one of their 200 by 300 square meter research plots. To lure the squirrels, Sheriff and Salli bait 75 traps with fresh pieces of carrot. An hour and a half later, they check each one and the real work begins.

Monday, Aug. 1

Toolik Lake, Day 8: Team Squirrel

Monday was bright, clear and windy—perfect weather for trapping ground squirrels in the Atigun Gorge.

Fat, furry rodents with black-tipped tails that switch back and forth as they gallop across the tundra, ground squirrels spend most of their time in hibernation. They emerge in the spring to feed, fight and breed, ducking back down into their burrow once the snow covers the ground.

University of Alaska researcher Michael Sheriff is studying how these cute but quarrelsome rodents respond to warming temperatures in the Arctic. To do that, he’s comparing squirrel populations near Toolik Lake, where snow has increased over the past 10 years, with those 13 miles to the south in Atigun Gorge, a windy corridor where snow cover disappears earlier in the spring and returns about two weeks later in the fall.

Ground squirrels at Atigun are waking up earlier than their Toolik counterparts. Sheriff wants to know how that longer growing season will affect ground squirrels’ reproductive success and ability to feed themselves. If breeding starts earlier as parts of the Arctic warm, will the plants and mushrooms that sustain them be available when they’re most needed?

“The juveniles may miss their food window,” said Sheriff, a post-doctoral fellow at the university’s Institute of Arctic Biology in Fairbanks. “We’re looking at not just can they adjust, but what that means for the ability of that population to survive.”

These are key questions for the North Slope ecosystem, because predators such as wolves, foxes, golden eagles all eat ground squirrels.

“Without ground squirrels, those species would be in real trouble,” said Sheriff.

To see how they’re doing, Sheriff’s team regularly traps squirrels at three plots—two at Atigun Gorge, and one at Toolik. They fit the squirrels with metal tags with identifying numbers and bright twists of colored wire, so that that can easily determine if the animal has already been trapped that day. Some squirrels are also taken back to the Toolik field station to have temperature sensors implanted in their abdomens so that researchers can track when they enter and leave hibernation, and when the females give birth.

In the fall, scientists also add sunflower seeds to one of the Atigun Gorge plots to simulate the extra food that researchers expect will become available because of climate change.

The shifts here in the Arctic could also provide researchers with a preview of how warming could affect groundhogs and other hibernating rodents in the lower 48, Sheriff said. “There are animals like this everywhere.”

Sunday, July 31

Sunday, July 31

View of the experimental plots at Toolik field station.

Tundra vegetation.

A mushroom.

Sunday, July 31

Toolik Lake, Day 7

Sunday is the day off for many of the researchers and staffers here at Toolik. Armed with a can of bear spray—the same kind of hot pepper solution you’d use to ward off muggers—I decided to go for a short hike beyond the lake.

I walked about mile on the boardwalks that connect a number of experimental plots. There is about eight miles of boardwalk here, constructed to protect the delicate tundra plants and soils from repeated tread of researchers as they collect samples.

Then I struck off into the open. Nobody there but me and my companion cloud of mosquitoes and black flies. The solitude of the tundra is quite an extraordinary sensation for someone who has lived in the bustling, crowded confines of downstate New York for the past eleven years.

Amazing views of the tundra’s unique vegetation: golden and garnet mosses, a variety of mushrooms, lichens and the types of shrubby plants such as willows that are becoming more common here as global temperatures warm.

Saturday, July 30

Researcher Jennie McLaren collects soil water samples.

She is also monitoring plant decomposition in plots where scientists have altered the vegetation by adding nutrients. She does that by placing leaf litter from different types of plants in mesh bags and measuring how quickly each breaks down.

Saturday was cool and wet, but science at Toolik carried on anyway.

Some people processed samples or did other indoor work in the lab trailers around camp.

Fieldwork continued as well. Rain paints, wool socks and neoprene “muck boots” provide some cover from the elements. Still, the researchers whose projects put them thigh-deep in Arctic streams are a pretty hardy bunch.

I zipped up my rain jacket and trotted over to the hillside plots southeast of the field station. That’s where scientists are investigating how changes in temperature, shade and nutrient levels affect the mix of vegetation on the tundra.

Plant ecologist Jennie McLaren of the University of Texas at Arlington was up on the boardwalks there picking up vials she had set out the night before to collect water from the soil. Later she will test them to see how much nitrogen is available in the soil of those plots.

As we walked the boardwalks that connect many of the experimental sites, McLaren told me about her research and talked about some of the changes observed here, and across the Arctic, as the temperature warms.

Typical tundra has a mix of low-growing plants and springy moss, with some low stands of birch or willow. But that’s shifting. In many places, those woody shrubs have been growing taller and are more widespread. Sometimes they shade out the low plants and mosses.

Experiments here at Toolik predicted some of those changes. We walked past a plot where scientists had been dosing the plants with lots of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium since 1989.

“The biggest change is that the shrubs have really taken over the fertilized plot,” McLaren said, pointing to willow and birch plants. “This is what you are seeing across the Arctic — the shrubs are really taking over.”

She’s also examining how the new plants in the fertilized plots at Toolik decompose — how quickly do birch leaves break down, compared with other tundra plants such as cotton grass or cloudberry?

To test that, McLaren has placed leaf litter from the different plant types on the soil in some plots. The plant material is in little bags made from window-screening material. The mesh allows the decomposed material to seep into the soil and gives access to the bugs and microbes that break down the leaf litter.

“The litter bags are used to see how quickly the carbon from the plant material is incorporated into soil,” McLaren said. That in turn will affect the rate at which carbon is released back into the atmosphere.

Friday, July 29

Back at Toolik, U.C. Davis researcher Jonathan Perez processes blood samples from the birds captured in the field on Friday. His colleague, Jesse Krause, extracts the relevant portion, which will be sent back to their home laboratory in California.

Friday, July 29

Scientists weigh the captured songbirds by putting them in a mesh bag suspended from a scale. After about half an hour of scrutiny, the birds are set free.

Friday, July 29

Checking in on migratory songbirds. Researchers take blood samples and measurements, weigh the birds, and determine what stage of molt the birds are at. Then the birds are banded and put in little bags to chill out before their blood is taken one last time.

“It’s like an alien abduction,” joked U.C. Davis researcher Karen Word.

Friday, July 29

Once snared, the birds are measured and banded. Researchers take blood samples twice over a 30-minute period to determine their stress levels.

Here, U.C. Davis researcher Karen Word blows on a captured songbird. The technique exposes the bird’s internal organs and allows scientists to estimate fat levels. Then she measures its wing feathers.

Friday, July 29

U.C. Davis Researcher Jesse Krause holds up a speaker to broadcast a recording of a Gambel’s white-crowned sparrow. Then he listens for the “chips,” or response sounds from nearby birds.

Krause and the fine-meshed net used to trap the birds.

Saturday, July 30

U.C. Davis researcher Jonathan Perez traps a Gambel’s white-crowned sparrow in a net, then sprints down to take blood samples from the bird. His team is tracking how songbirds that nest in the Arctic fare as parts of the tundra change.

Friday, July 29

On Friday I ventured south of Toolik, to a valley below the majestic peaks of the Brooks Range, with a team of researchers tracking how songbirds that nest in the Arctic fare as tundra vegetation shifts in response to global warming.

As temperatures here warm, woody shrubs such as willow and birch are becoming increasingly common in some areas previously dominated by low-growing plants. The shifts could alter the breeding success of songbirds that pass through American backyards on their migrations.

For instance, birds may be able to find more shelter from predators in stands of willow. But scientists don't know how the extended growing season seen here will affect food sources such as berries, or, more importantly, the insects that the songbirds rely on to feed their young.

"If the insects peak when the birds' eggs are on the nest, they'll have nothing to feed their young," said Jonathan Perez, an environmental physiologist from U.C. Davis who works with birds.

His team is collaborating with Natalie Boelman, a scientist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, on a project analyzing how these shifts will affect the complex interactions between birds, insects and plants in the Arctic.

Saturday, July 30

Hiking in to the Kuparuk River.

The Alaskan pipeline is a constant here. Along with Dalton Highway and the gravel pits used to maintain the road, it’s a reminder of the human imprint on the largely unpopulated North Slope of Alaska.

Friday, July 29

Chasing down the swift and increasingly devious young Arctic grayling in Oksrukuyik Creek. The older they get, the more wily the fish become. At this stage in the summer often entire teams must resort to herding a handful of fish toward their colleagues’ waiting nets.

Saturday, July 30

Catching bugs with homemade fly traps. Like much fieldwork, it’s an exercise in improvisation to suit the particular needs of a setting and at times limited scientific budgets.

Scientist Mike Kendrick collects the samples about once a week, wrapping them carefully in plastic wrap. He’ll send them back to Tuscaloosa, where he’ll go through the results on his return from Toolik.

Thursday, July 28

Eve Kendricks picks through insects netted from Oksrukuyik Creek. She is wearing a “bug shirt,” an extremely popular item of clothing among the squads of scientists and students who labor in clouds of mosquitoes. The bug shirt has lots of mesh to let in air, and a mesh mask over the face to prevent breathing in black flies and other pesky insects.

The vials will be tested to see whether the insects’ DNA matches those of species in other streams. Researchers are comparing how shifting temperatures affect the pace of the insects’ development, in part to determine whether extended open water seasons and other changes will change when the bugs are available as food to fish such as Arctic grayling.

Thursday, July 28

Mike Kendrick employs a kick net to skim aquatic invertebrates from the bottom of Oksrukuyik Creek.

Thursday, July 28

After visiting the crew tagging fish at the Kuparuk River, I headed over to Oksrukuyik Creek later on Thursday with aquatic invertebrate researcher Mike Kendrick. He is tracking mayflies and other insects at a number of North Slope streams in an effort to understand how temperature and climate shifts could affect the food web that connects the bugs, the fish and aquatic vegetation.

Kendrick collects insects by scooping them up from the stream with a variety of nets, and with homemade traps left out flat on rocks in the river. Painted with a gooey substance, the squares act like homemade flypaper.

On Thursday his wife, Eve Kendrick, sorted the insects out with tweezers, dropping different insects into vials according to type. Their DNA will be analyzed to determine whether they are the same exact species as insects collected at other rivers.

A high school science teacher from Tuscaloosa, Eve Kendrick is up at Toolik this summer on a National Science Foundation grant for educators. She is working on a project tracking how “young of the year” Arctic grayling respond to shifts in temperature and nutrient content in streams. That day she did double duty, catching 3-inch-long young fish with nets along with a fleet of mostly undergraduates, then moving upstream to assist with the insect work.

Thursday, July 28

Video: Thursday, July 28

Robert Golder of the Marine Biological Laboratory inserts a tracking device into an Arctic grayling caught in the Kuparuk River on Alaska’s North Slope. Researchers are monitoring how these fish migrate to determine if warming temperatures have affected their movements.

Photos: Thursday, July 28

Scott Starr, a doctoral student at Texas Tech in Lubbock, Texas, nets an Arctic grayling he has just caught in the Kuparuk River.

Starr and researcher Mike Kendrick of the University of Alabama measure the fish, which will be inspected to see if it is one of those tagged with a tracking device to monitor its migrations up and down the river.

Video: Thursday, July 28

Jeremy Liszewski catches an Arctic grayling in the Kuparuk River. Researchers have fitted many grayling here with transmitters to track their migrations. This fish will either be equipped with a tracking device or, if it already has one, be recorded so that scientists know which part of the river it frequents at which time of year.

Photo: Thursday, July 28

Scientists have been collecting information on Alaska’s Kuparuk River sinc?e? ?t?h?e??1?9?7?0?s?,? ?making it ?an ideal? ?p?l?a?c?e? ?t?o? ?e??x?a?m??i?n?e? ?how a warming climate could affect streams and the fish, plant and insect life they contain.

I?ce in the river is breaking up an average of two weeks earlier — in late May instead of early June, said Michael Kendrick, a graduate research assistant? from the University of Alabama who studies aquatic insects. And the Kuparuk is taking about two weeks longer to freeze in the fall, with ice forming in late September instead of earlier in the month.

Researchers are particularly interested in how those changes could affect the food web in the river — will the insects that such fish as Arctic grayling eat be around for the extended season?

“The river is open for a whole extra month,” Kendrick said as he led me over springy tundra by the water’s edge. “Are the insects emerging sooner? Are they maturing faster? How do fish respond to it, and does it affect their migration?”

One group of scientists a??????t the Toolik Lake field station is installing transmitters in grayling here to track their movements between the river and Green Cabin Lake, the headwaters where they spend the cold winter months when the river is frozen solid.

They are also monitoring fish in Oksrukuyik Creek, a smaller stream about 12 miles northeast of Toolik Lake.

At what scientists call “Ox Creek,” Kendrick is collecting mayflies, stone flies and other aquatic invertebrates so he can compare their development with the same species in the Kuparuk River and with even warmer streams to the north. “I’m trying to predict how these species might respond to climate change,” he said. “These warm streams are representative of what is to come.”

Wednesday, July 27

Takeoff from Toolik. On Wednesday we traveled by helicopter to several sites on the tundra. The aerial views of the braided rivers and beaded streams common to this landscape are amazing; my camerawork less so.

Wednesday, July 27

Measuring thaw depth on the tundra. We had to helicopter in to this remote spot, which is healthy tundra but close to the site of 2007 fire that was the biggest such burn to date in the Arctic tundra.

Wednesday, July 27

After we landed, Gus Shaver looked up from unpacking the helicopter and asked Adrian Rocha: “Did you get the bear spray?”

He wasn’t kidding. They do get grizzlies out there, including one that mangled one of Rocha’s monitoring towers. Hence bear spray, which is essentially a fire extinguisher-size can of pepper spray. The perils of Arctic science!

Wednesday, July 27

Thanks, pilot Bill!

Wednesday, July 27

Wednesday, July 27

Wednesday, July 27

High above the tundra.

Wednesday, July 27

Wednesday, July 27

Shaver stands on land that has tumbled down toward Horn Lake after the permafrost beneath it thawed. Scientists called that a “thermokarst.” It’s a response to warming permafrost that could also trigger changes in the lake’s ecosystem, and potentially release more carbon into the atmosphere.

Wednesday, July 27

Cloudberries ripening in a stretch of tundra burned in the 2007 fire.

Wednesday, July 27

Shaver and Rocha measure the depth of permafrost at the unburned tundra near the burn site.

Wednesday, July 27

Scientist Gus Shaver amid the flowering cotton grass at the burn site. His colleague, Adrian Rocha, and the 3-meter tall tower that measures carbon exchange out on the tundra. It’s surrounded by an electric fence to keep out bears (more on that later).

Wednesday, July 27

The tundra from above.

Shaver displays a cross-section of unburned tundra.

Wednesday, July 27

Wednesday we took a helicopter ride out about 27 miles from Toolik Lake to what scientists here call “the burn site” — about 400 square miles of tundra that was scorched during a 2007 fire.

The Anaktuvuk River fire was the largest such fire on record. Some scientists think this unprecedented event shows that future fires on a tundra made warmer and drier by climate change could amplify the effects of global warming. The fire released carbon that had been locked in the peaty tundra soil, according to research and fieldwork conducted by University of Florida scientist Michelle Mack and her co-authors, including Gus Shaver of the Marine Biological Laboratory.

The fire also changed the ecosystem there. The dark, charred surface retains more heat than the previous mix of mosses and tussock grasses. Scientists think the loss of the insulating surface soil layer could destabilize the permafrost below, something that could lead to further releases of carbon into the atmosphere. Their paper on the subject is being published Thursday in Nature.

On Wednesday we inspected the main burn site, and compared growth of plants there and thaw depth of the permafrost with an unburned site nearby. MBL scientist Adrian Rocha has set up instrument towers at both sites that measure how much carbon the tundra there absorbs and releases into the atmosphere.

Once a stark contrast, by now the difference between the two locations is difficult to detect even by air. From above the recovering burn scar looks slightly browner than the unburned tundra, which is more of a drab olive color. But on the ground both sites looked alive with growth, dotted with flowering cotton grass and ripening cloudberries, a reddish-amber berry with a pleasingly tart taste.

“It’s wonderful out here,” Shaver said, as we walked back over the springy tussocks toward the waiting helicopter. “You really are alone.”

Later in the day we stopped over at Horn Lake, where thawing permafrost has resulted in a unique sort of erosion that scientists called “thermokarst.” As the ice in the permafrost melts and water drains away, the ground slumps, forming hollows and — in this case — tumbling down toward the water’s edge.

Just before heading back to the Toolik field station, we took a dramatic detour and flew over Atigun Gorge at the foot of the Brooks Mountain Range. Arctic sheep (known as Dall sheep) grazed on the steep, stony slopes above the Atigun River.

Wednesday, July 27

We’re going up in a helicopter to check out burned sections of tundra from a sweeping 2007 fire. Pictures and video to come!

Tuesday, July 26

The Brooks Range.

Tuesday, July 26

Wildflowers.

Tuesday, July 26

View of the mountains, and another experiment plot, this one on the heath tundra near the old runway where scientists pitched their tents back in the 1970s, in the first incarnation of the Toolik research station.

Tuesday, July 26

This is the view from the Toolik dining hall, where on Tuesday night we had a very excellent Indian meal.

Tuesday, July 26

Tuesday, July 26

Aww alert.

Ground squirrels are plump and plentiful around Toolik. This little guy got vertical to check out the scene.

Tuesday, July 26

Tundra greenhorns like myself are advised to wear mosquito head nets to ward off/avoid inhaling the literal clouds of buzzing, biting pests up here. Glamorous! But definitely helpful.

Tuesday, July 26

Instruments inside the greenhouse measure conditions there.

A weather station tracks temperature, wind and more.

Tuesday, July 26

Scientist John Hobbie replaces plastic sheeting over a “greenhouse” plot where researchers have raised the temperature to see how tundra plants respond to a warming environment. The result: an increase in shrubby plants such as willow and birch.

They’re also shading out some plots to see how limiting light affects vegetation.

Tuesday, July 26

On Tuesday afternoon I joined scientist John Hobbie of the Marine Biological Laboratory out on a hill about three-quarters of a mile southwest of camp.

Hobbie is one of the founding scientists who set up the Arctic Long Term Ecological Research site here, on what was once a camp for workers building the oil pipeline. He was working out of Barrow, Alaska, back in the 1970s and saw the great potential for science at Toolik Lake. The camp started out as a trailer or two, with scientists living in tents and washing their dishes twice a week using water-filled trash cans hauled up from the lake. Three decades later, the field station can house up to 150 visitors and has a number of labs where complex chemistry and other science can be done on site.

On Tuesday, Hobbie set out to collect samples from experimental vegetation plots set up years earlier by his colleague, Gus Shaver. Some are covered in plastic sheeting to simulate the effects of global warming on tundra plants. Others are draped in black mesh to shade out the plants below. And some are being artificially fertilized with nitrogen and phosphorus to determine how those changes might affect the mix of vegetation here on the North Slope.

“It’s been about the same vegetation for 7,000 years,” Hobbie said, dozens of mosquitoes hovering around him like a cloud. “They know that from the pollen in the lake.”

But the tundra plants have been changing in recent decades, transitioning in some places from low vegetation to woody shrubs, such as birch and willow. Scientists know that from comparing aerial photos with some from the 1940s, and through satellite imagery.

That transition could change migratory habits of birds who come here to breed, and of caribou herds, who prefer low, slow-growing lichens to taller, shrubby plants.

Tuesday, July 26

A scientist trudges up the tundra to access one of the experiment sites in the hills surrounding the Arctic Long Term Ecological Research station. The white plumes in the distance are dust kicked up by trucks on the Dalton Highway, which runs along the oil pipeline from Prudhoe Bay.

Tuesday, July 26

Stream emptying into Toolik Lake, and a view of the field station from across the lake.

Tuesday, July 26

Colorado State scientist John Moore, top, and his soil buckets.

Tuesday, July 26

View of the Brooks Range from the Arctic Long Term Ecological Research site at Toolik Lake.

Tuesday, July 26

The sun came out late Tuesday morning after a foggy start. The temperature went up about 10 degrees! Off with the fleece, on with the mosquito-repellent-impregnated shirt and pants.

I spent the late morning and early afternoon in the labs, which are in converted trailers. One group working under Marine Biological Laboratory professor Gus Shaver is researching the effects a large 2007 tundra fire had on the ecosystem here and its ability to act as a carbon sink. See pictures from the previous posts for more.

Another group headed by scientist John Moore of Colorado State University is looking at soil samples from the burn site and counting the number of bugs there. Small insects, such as fly larvae, beetles, spiders and mites, are part of what Moore calls “the decomposer subsystem.”

Those bugs, along with bacteria, protozoans and fungi, help break down leaf litter through decomposition. Moore is interested in whether the big fire will affect how quickly organic matter on the tundra is decomposed — if the cycle speeds up, the tundra could switch from being a major carbon sink and become a source of carbon, releasing it to the atmosphere.

As Moore explained it to me, plants “fix” carbon dioxide by absorbing it from the atmosphere. Decomposition releases that carbon back into the air. Human activities have altered the balance of that exchange, he said, “and that has consequences.”

What those may be is still unclear. Faster decomposition could spur an uptick in carbon release from the tundra. But Moore said a spike would likely balance out over time.

Moore’s researchers labor in what around Toolik is known as “The Green Tent” — a tent lab whose green exterior lends a ghostly color to the proceedings.

Inside, his team separates the bugs from the soil samples using a lightbulb to heat up the inside of a bucket where the sample is stored. The heat irks the insects, which climb down a funnel to get away and land in a pool of alcohol. The team then counts the number and variety of critters in each sample as a way of determining differences between the burned and unburned tundra.

Tuesday, July 26

This tin contains rhizomes from cotton grass. Rhizomes are rootlike underground stems that contain the part of a plant where new cells grow.

Tuesday, July 26

A hunk of Arctic cotton grass, one of the most dominant plants up here in the Arctic. It’s one of the few plant species that was not killed by the fire because it grows in a dense, moist tussock whose interior is able to withstand that heat.

Tuesday, July 26

Home sweet home. This is the tent I’m sharing with two other visitors during my stay. It was brought over from Greenland, so I’m told. Temperatures here are not that chilly so far, but there is an electric heater inside, just in case.

Tuesday, July 26

We pulled into Toolik Lake on Monday night, after a three-plus-hour van journey south over the Dalton Highway from Prudhoe Bay.

About 130 scientists and other workers are at the station this week. It’s the high season, with accommodations nearly full at the various prefabricated dorms and Tyvek tents that house visitors and staff. We’re about 150 miles north of the Arctic Circle.

Toolik is bustling, its labs filled with scientists and research assistants analyzing water samples, vegetation and results from carbon measurements out on the tundra. Some research sites are right by the camp; others are visited by van or by the helicopters parked at the entrance to the field station.

Everything is trucked in: food, water, fuel for the generators. Food waste is burned in an on-site incinerator. Recyclables and sewage get trucked out. To limit wastewater, there are only two flush toilets and showers are rationed — once every other day, and keep it to two minutes, please, we were advised. Tall outhouses known as “towers” and portable toilets serve most of the camp.

I’m off to the lab, where a team of “pluckers” is sorting samples of vegetation from the tundra to determine the impact of a 2007 fire that left much of the area charred. Fires were once unusual here, but they may be becoming more common as a result of climate change. Researchers are interested in how quickly the plants are growing back and how the fire affected the absorption of carbon dioxide by plant life. More to come!

Monday, July 25

Toolik Lake

Monday, July 25

10:45 p.m. Most people are either in bed, working inside to escape the mosquitoes or partaking of the lakeside sauna (clothing optional!).

Monday, July 25

Still life with antlers, tire.

Monday, July 25

Monday, July 25

Toolik Lake

Monday, July 25

Rest stop, with bear-proof garbage cans.

Monday, July 25

Dalton Highway

Monday, July 25

Prudhoe Bay (settlement/depot farther inland than the actual bay) viewed from the North Slope Haul Road, aka Dalton Highway. From here it’s a three-hour drive to Toolik Lake, along the pipeline and a river whose name I am too tired to recall or properly spell.

Monday, July 25

Monday, July 25

Flying from Anchorage to Deadhorse Airport, Prudhoe Bay.

Monday, July 25

River emptying into Bootlegger Cove.

Monday, July 25

Monday, July 25

Wildflowers by the Tony Knowles Coastal Bike Trails in Anchorage.

Monday, July 25

Time for a quick bike ride on the coastal trail in Anchorage before hopping the plane to Deadhorse. Next time I’ll wear rain pants.

Monday, July 25

Low tide, Bootlegger Cove, Anchorage.

Monday, July 25

After a long day traveling, I finally arrive in Anchorage. I’ve never heard so many Southern accents this far north! The city is a big hub for pipeline workers, many of them from Houston, Louisiana and Alabama, by the sound of talk in my shuttle en route to a motel near Lake Spenard.

The workers are young, mostly male and scrupulously polite. They’re also filling hotel trash cans with ice to party before they fly out to Deadhorse tomorrow for another four-week stint on the pipeline. “Room 148 is where the beer is, ma’am!” I am told.

Fossil fuels and other natural resources play a huge role in Alaska’s economy. These industries provide jobs and income not just for state residents, but for many workers (and corporations) in the Lower 48.

Of course, the apparent result of human combustion of oil and other fossil fuels is the reason I’m here. Even as workers extract long-buried carbon from the earth, a 2007 fire that swept across the warming Alaskan tundra released even more greenhouse gases straight into the atmosphere.

It’s tough to connect individual weather events like the recent scorching heat in New York City with larger long-term trends in climate. But after a steamy weekend like the one much of the Northeast and Midwest endured, it’s certainly food for thought.

Monday, July 25

Seaplanes! I am definitely in Alaska. By the way, it’s 11 p.m. and I took these with no flash.

Monday, July 25

The Great Lakes’ sheer expanse is just stunning, especially when viewed from above. I’m a West Coast transplant who’s lived in downstate New York for 11 years, so I don’t have a lot of exposure to these astonishing inland seas. Note to self: Amend that.

I thought Lake Erie was big, and then we flew over Lake Michigan. Damn. Marvelous — and, of course, subject to the same stresses as Long Island coastal waters. Sewage, invasive species, etc…. Asian carp, anyone?

Sunday, July 24

Sky icebergs east of Lake Erie

Saturday, July 23

Packing.

Friday, July 22

With the mercury at 100 degrees in Islip, it’s hard to fathom the thought of fleece and Gore-Tex hiking boots. But that’s what I’ll be wearing on Monday when I arrive at the remote Toolik Lake field station on Alaska’s North Slope.

For the next two weeks I’ll shadow climate scientists as they discover how global climate shifts affect plants, animals and Earth’s capacity to absorb or release greenhouse gases. Stay tuned for photos, videos and blog updates from the field.

Climate change is moving fast at the North Pole, some 3,290 miles from Long Island. Researchers there are tracking carbon emissions from thawing tundra, monitoring birds and documenting changes in plant life there as the world warms. Their findings will help us understand the global consequences of climate disruption, and identify changes that we could eventually encounter in our own backyards.

For instance, scientist Natalie Boelman at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory has spent the past two summers at Toolik studying migratory songbirds, such as the Dark-eyed Junco, that return to the Arctic each summer to breed. “We’re trying to figure out how these changes in the tundra affect their reproductive success, and ultimately affect how many make it back to your bird feeder,” Boelman said.

See you in Alaska!

Details on the charges in body-parts case ... Gilgo-related search continues ... Airport travel record ... Upgrading Penn Station area