On a mission to give final dignity to Negro Leagues players

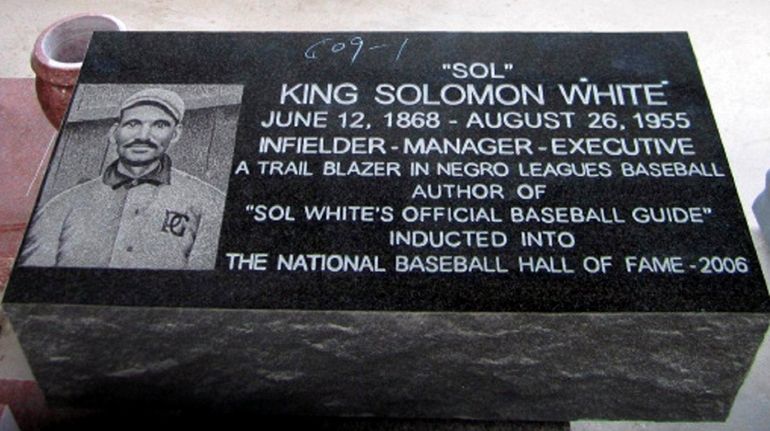

Baseball Hall of Famer Sol White's gravestone at Frederick Douglass Memorial Park on Staten Island. Solomon White was a former Negro League player who spent years on Long Island and died in Central Islip. Credit: Handout

As Negro Leagues baseball star Solomon White was being enshrined in Cooperstown, his remains were in an unmarked grave, where they had been for more than 50 years.

White’s career began near Long Island’s Argyle Hotel in Babylon Village in 1887. When he died at 87 in 1955, his body went unclaimed and was unceremoniously placed in a grave on Staten Island.

Only 25¢ for 5 months

As Negro Leagues baseball star Solomon White was being enshrined in Cooperstown, his remains were in an unmarked grave, where they had been for more than 50 years.

White’s career began near Long Island’s Argyle Hotel in Babylon Village in 1887. When he died at 87 in 1955, his body went unclaimed and was unceremoniously placed in a grave on Staten Island.

That indignity continued even beyond White’s 2006 induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Decades after White’s death of a pulmonary embolism at Central Islip State Hospital, a monumental injustice is being addressed by the Negro Leagues Grave Marker Project. Four years ago, a headstone was placed on White’s grave at Frederick Douglass Memorial Park.

White’s is one of 38 headstones placed by the project, which was started in 2004 by Jeremy Krock, a Peoria, Illinois, anesthesiologist.

Dr. Jeremy Krock, head of the Negro League grave marker project at the grave of Jonathan Boyce Taylor. Credit: Family photo

Krock, who is white, said the case of Jimmie Crutchfield first piqued his interest. Krock said his relatives had followed Crutchfield, who worked in the coal mines of Ardmore, Missouri, before playing in the Negro Leagues with “Cool’’ Papa Bell and Satchel Paige as teammates. “My family didn’t see a color barrier,’’ Krock said.

Krock said he discovered that there was no headstone on the grave of Crutchfield, who died in 1993 and was buried in Burr Oak Cemetery outside of Chicago. “I realized he had no family,’’ Krock said. “No one was there to make sure his grave was marked.’’

Krock set out to raise funds, about $1,500, to purchase a marker for Crutchfield, who in 1932 played in the first Negro League World Series before 45,000 at Yankee Stadium. He found interest from the Society for American Baseball Research. “Members started sending me checks, made out to Jeremy Krock, sight unseen,” he said. “Jimmie was beloved in this community of historians. They sent me so much money that I started hunting other graves.’’

Among the 38 gravestones placed by Krock’s group are Hall of Famers White, Frank Grant and Pete Hill. Ron Hill, a 72-year-old great nephew living in Los Angeles, is hoping to see the headstone. “My father always said to us there was a baseball player in the family,’’ Ron Hill said. “He didn’t say how good he was.’’

Krock said, “We’ve done Hall of Famers, we do people no one has ever heard of. Pete Hill was a labor of love over many years, with many people helping out. We knew that he collapsed at a bus stop in Syracuse, but that was all we could find. His death certificate said his body was transported to Chicago for burial. I searched transit records, funeral homes, traditionally black cemeteries, and even the cemetery where his son was buried in Gary, Indiana. Finally, I discovered his burial in a Catholic cemetery in Alsip, Ill.’’

Hill now has a marker in Holy Sepulchre, where former Chicago mayor Richard J. Daley was laid to rest. Burr Oak Cemetery, where Crutchfield is buried, is also located in Alsip.

Most of the players have no living relatives, but sometimes the Project finds a family member. Patricia Hawkins, daughter of William “The Human Vacuum Cleaner’’ Robinson, was thrilled when Krock contacted her about placing a marker on her father’s grave in 2010. He died in 2002 at 98.

Gravestone of Negro League baseball player Bobby Robinson Credit: Jeremy Krock

“What it felt like was that someone cared enough to do a project for these men based on the fact that they may have been forgotten,” she said. “There may have never been anyone left to think about to talk about to give thought to their legacy.’’

Hawkins said she could not afford to put a headstone on her father’s grave. “His savings were not big, my mom passed away prior to him,’’ Hawkins said from Chicago. “We were raising five foster children in addition to five of our own. What he did have was spent on his care. Of course, we talked about the marker but that was having to be put back on the back burner. the expenses of life you know. Just the walk of Life.’’

Hawkins said her father told stories of his life in the Negro Leagues. “White owners would sometimes say if it wasn’t for the color of his skin you’d be playing for us. He talked about how they had to go to the back of the restaurant, they couldn’t, of course, go in. He said he ate a lot of peanut butter and crackers because he would go in the store and buy it. He just refused to go to the back door and be served.

“He talked about how he could not look white men in their eyes. That’s one thing he insisted on us. Whenever we talked to him or anyone, he insisted we make eye contact. He said based on where he came from — which was nowhere in his words — he didn’t allow people to get into his head because of racism. He said he saw it, he knew it for what it was but he never allowed it to belittle who he knows he was.’’

Krock is not always successful in his search. Right now he is seeking the burial site of William Bedford, who was struck by lightning while playing in Atlantic City in August of 1909. His body supposedly was shipped to Cairo, the southern-most city in Illinois, located at the confluence of the Mississippi and Ohio rivers. “Unfortunately, because of the high water table, cemeteries were outside of Cairo and records are poor,’’ Krock said. “I have been unable to locate his burial site in the Cairo area.’’

Krock worked on Sol White’s marker with Ralph Carhart, who heads the 19th Century Grave Marker Project in New York. Both have been working on the case of Cristóbal Torriente, a Cuban outfielder in the Negro Leagues who died in 1938 and was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2006. They had been advocating for Torriente to have a marker in Calvary Cemetery in Queens. A spokesman said cemetery records indicate Torriente is buried in a non-titled — or pauper’s grave, where markers are prohibited.

Joseph Zwilling, director for the office of communications for the Archdiocese of New York, recently asked officials at Cavalry about the Torriente matter and said Torriente has been added “to their list of notable individuals buried in the cemetery, along with the location of his grave. That list is given to those who ask where famous people are buried. Along with that, they have also put a small cross, listing his name, date of death, and section grave number nearby the grave where he is interred.’’

However, Carhart said Cuban officials said that Torriente’s remains are in Cuba and DNA results are expected soon.

Krock’s group did not have to chase down one former Negro Leagues player buried on Long Island. Richard “Cannonball’’ Redding, who played for Brooklyn Royal Giants and was said to have struck out Babe Ruth three times on nine pitches in an exhibition game, is buried in the Long Island National Cemetery in Farmingdale. A World War I veteran, Redding has a headstone, a spokesman for the cemetery said.

Krock said there are likely “hundreds’’ of players lying in unmarked graves in cemeteries across the country. “We have death records from the Negro Leagues. I go state by state. It’s just a never-ending project,” he said. “It’s a good never-ending. I’m glad we’re able to fulfill it, one player at a time.’’