Protests against police misconduct accomplish what cold, hard statistics could not

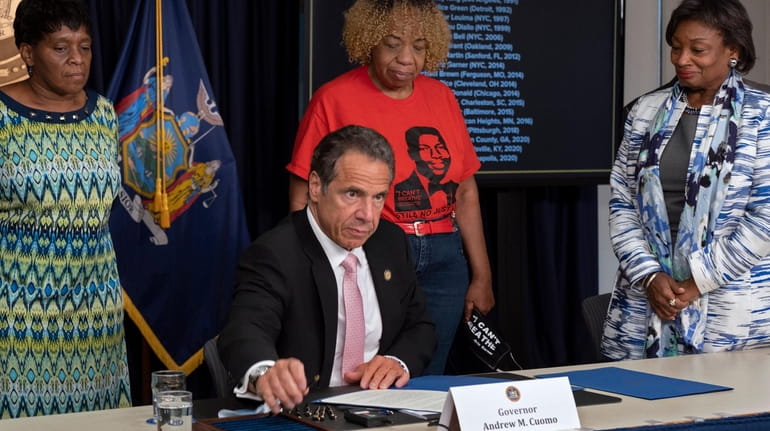

Gov. Andrew Cuomo signs a series of bills that will create police reforms in New York State on Friday. From left is Valerie Bell, mother of Sean Bell, Gwen Carr, mother of Eric Garner, and State Sen. Andrea Stewart-Cousins. Credit: Craig Ruttle

Police reform in New York State is long overdue.

And, yes, that's the case — even though Democrats in Albany managed to push a package of institutional reforms through last week with the speed of light.

Among them were common sense changes, some even supported by Republicans, which included banning chokeholds and mandating body cameras for police.

But the big one was the repeal of 50-a, a statute that shielded police disciplinary records from public view.

Police unions, backed by Republicans, said the move could put the lives of officers in danger.

But the change includes some protections for police, including redacting some personal information.

The overarching change, however, is that, for the first time in decades there could be greater public scrutiny on how police disciplines are handled, at least in theory.

Which, in theory at least, could shine a light not just on individual officers but, more important, on the functioning and internal culture of the departments themselves.

In 2017, a Newsday/News12 investigation, called "Unequal Justice," found that blacks, Hispanics and other minorities in Nassau and Suffolk counties were far more likely than white Long Islanders to be arrested and wind up behind bars for a group of crimes that experts called the suburban equivalent of charges stemming from “stop and frisk” tactics.

"Nonwhite Long Islanders were arrested at nearly five times the rate for whites" for charges including resisting arrest, obstruction of governmental administration, criminal trespass and a host of drug-related offenses, according to the project's analysis of police and court records from 2005-2016.

The disparity in arrests carried over into the disparity in the numbers of nonwhite Long Islanders who end up in jail.

The story highlighted a systemic pattern of unequal enforcement of the law by police and courts.

The result was … silence.

Was it because no one was surprised?

Or that a fix would be so big, and so complex that it would be folly to even try?

Could it have been both?

Tell that to Keith Bush, an African American who spent 33 years in prison for a murder he did not commit.

Or to the family of Jo'Anna Byrd, a black woman who was killed by her boyfriend, who was a police informant.

In that instance, police failed to act to protect Byrd — to the consternation of then-Nassau legislative majority leader Peter Schmitt, a Republican who ended up before U.S. District Judge Arthur Spatt, who died Friday, after speaking out publicly after reading an internal report on Byrd's killing.

"There are 22 police officers in this county who were mentioned in that confidential internal affairs report who ought to be ashamed to look at themselves in the mirror every morning when they get up to shave, much less be wearing the badge." Schmitt told News12 Long Island in February 2012.

"Orders of protection were ignored … Mandatory arrests were called for and not performed, giving a cellphone to the prisoner when he was behind bars and allowing him to call the victim 35, 40 times, and on and on and on," said Schmitt.

Defense lawyers argued that Schmitt had not defied a gag order — requested by a police union — but merely had repeated what Newsday already had reported.

Nonetheless, Schmitt, who later would later die of a heart attack, was held in contempt.

How did the police department handle the 22 officers Schmitt had pointed to?

Residents don't know, and a legal settlement with Byrd's family is sealed.

In Suffolk, long before a white teenager stabbed Marcelo Lucero, an Ecuadorian immigrant, to death in Patchogue in 2008, Suffolk police had ignored complaints about violence, including beatings, against Latino immigrants.

The county later entered into an agreement with the U.S. Justice Department to satisfy allegations of discriminatory policing against Latinos.

But who knows how the department handled officers who ignored the complaints?

Residents do know how the police department handled complaints and disciplinary proceedings involving James Burke, Suffolk's former chief of department.

That came out in last year's trial of Burke's one-time boss, former Suffolk County District Attorney Thomas Spota.

A retired internal affairs officer, who sat in on the trial, had leaked Burke's file to a Newsday reporter, as Burke was under consideration to lead the department.

Plentiful officers believed Burke to be unfit to lead.

But Burke went on to become chief of department, the top uniformed job, despite having been disciplined for losing his service weapon and having sex with a prostitute in a police car. He later would be convicted and imprisoned on charges stemming from the beating of a prisoner who had stolen a duffel bag from Burke's vehicle.

Changing the culture of policing on Long Island will be hard, but that does not mean it's not necessary — or that it's impossible to do.

What's outrageous is that it took the death of yet another black man at the hands of police in Minneapolis, twinned with an international outpouring of grief and anger to get the job started.

Details on the charges in body-parts case ... LIRR discounts in NYC ... BOCES does Billy Joel ... Hottest day of the year