Victims reflect 2 decades since 1993 LIRR massacre

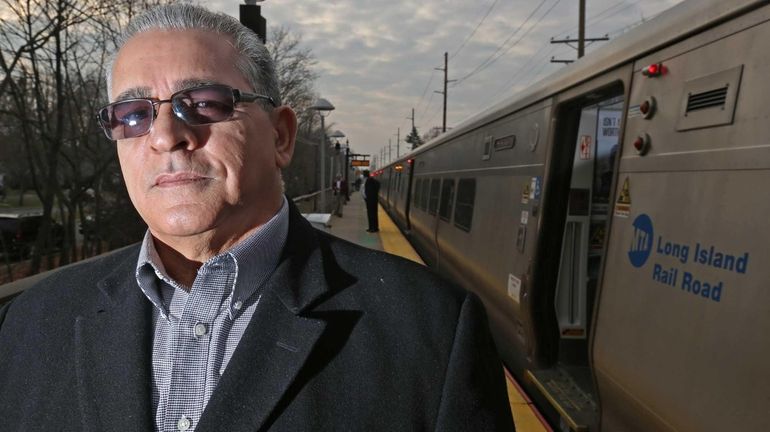

Robert Giugliano survived the LIRR massacre 20 years ago. He was shot and later faced down the shooter at the trial. In the 20 years since, he has suffered from the aftermath. He is shown at the Merillon Ave LIRR station near where the shootings took place on board a train. (Dec. 4, 2013) Credit: Chuck Fadely

Robert Giugliano, who was shot in the chest 20 years ago in the Long Island Rail Road shootings that left six dead, stared down his perpetrator in court, famously asking the judge for five minutes alone with him.

The shootings had made Giugliano a crime-victim celebrity. But after the trial was over, he had to live with his thoughts: the image of the woman who died at his feet. The helplessness he felt.

Only 25¢ for 5 months

Robert Giugliano, who was shot in the chest 20 years ago in the Long Island Rail Road shootings that left six dead, stared down his perpetrator in court, famously asking the judge for five minutes alone with him.

The shootings had made Giugliano a crime-victim celebrity. But after the trial was over, he had to live with his thoughts: the image of the woman who died at his feet. The helplessness he felt.

Giugliano fell into a deep depression. His marriage fell apart. Friendships ended. He saw a therapist.

Twenty years after Colin Ferguson wounded 19 and killed six with a 9-mm handgun on a Long Island Rail Road train near the Merillon Avenue station on Dec. 7, 1993, Giugliano says he's made peace. Ferguson was convicted of murder and sentenced to 315 years and 8 months in prison. He is not eligible for parole until 2309.

"Time healed me," Giugliano said recently at the Howard Beach home he shares with his second wife, Maria.

The killings aboard a suburban commuter train shocked the nation before mass shootings became something of an American epidemic, sparking a nationwide conversation about gun violence and the meaning of the Second Amendment to the Constitution. And it spawned a congresswoman: Rep. Carolyn McCarthy (D-Mineola), whose husband, Dennis McCarthy, was killed and son Kevin McCarthy severely injured in the shooting. She has served in Congress for 17 years, pushing for restrictions on the purchase of guns.

McCarthy, who is being treated for lung cancer, said in a statement that she was proud Congress had taken "modest steps" to prevent "senseless tragedy in this country," since she was first elected.

"Twenty years later, I know there is much more for our nation to accomplish in this light," the statement said. "But as I reflect on that infamous day I cannot help but to feel not only fortunate that my miracle, my son Kevin, is alive today, but also blessed to have two beautiful grandchildren."

The victims' struggle

Ferguson, a Jamaican immigrant living in Brooklyn, opened fire in a train car on the 5:33 p.m. from Penn Station, soon after it left the New Hyde Park station.

Joyce Gorycki, whose husband James was killed, also became an activist. At her Mineola home, dozens of mementos illustrate her work on gun issues. But she's frustrated at continued gun violence.

"When are the people going to wake up?" said Gorycki, the Long Island chair of New Yorkers Against Gun Violence. "Look at what happened in the school in Connecticut and that didn't change anything," she said, referring to last December's killings of 20 students and six educators at a Newtown elementary school. "They were babies, babies. Come on, it's time for the country to step up."

After the Ferguson trial, she moved to Arizona. That lasted 10 months. She missed New York. She never remarried, though she says she's dated and been in love.

In the aftermath of the shooting, Brian Parpan, a retired Nassau homicide detective who led the Ferguson investigation, doled out hugs and advice. He accompanied some victims to their counseling sessions.

"It was not the most challenging case," he said. "But it was the case that I would end up putting the most into beyond the investigation because of the people. Being there for them."

As the trial was nearing, Carolyn McCarthy called him, worried about her son testifying. Parpan and the lead prosecutor, Nassau County Assistant District Attorney George Peck, said Kevin McCarthy didn't need to take the stand, where he could be questioned by Ferguson, who acted as his own attorney.

But he would take the stand anyway. "I have to do it for my father," he told Parpan.

Peck is a judge now. It was the last case he tried. The notes found in Ferguson's pockets, titled "Reasons for this," included what Peck called some of the most damning evidence: "NYC was spared because of my respect for Mayor David Dinkins and Commissioner Raymond Kelly . . . Nassau County is the venue."

Peck said he worried Ferguson would sabotage the trial.

"It was not complicated as far as proving the case," said Peck. "The only thing I was concerned about was Ferguson losing control of himself. Because he was mentally ill. . . . We didn't want to try it twice."

Many victims were worried about Ferguson questioning them, so Peck organized a meeting to reassure them.

"They drew on each other," he said. "Any fear that they had was gone. Soon they were calling me, 'When is it my turn to testify?' "

Ferguson's time in prison

Ferguson, now 55, still isn't offering answers about his crime. In a prison in upstate Malone, he responded to a request for an interview with a one-page note.

"Should I consent to your interview, there is something in it for you and for a number of others, but nothing for me," Ferguson wrote. "If I am to give serious and speedy consideration to your request, I need the following done."

He asked for help getting copies of evidence. No interview was conducted.

Over the years, according to his inmate discipline records, he's been cited for assaulting staff, rioting, making threats and failing urine tests. He's in a special housing unit until next August and has been unable to participate in prison programming, a prison spokeswoman said.

Attorney Ron Kuby and his law partner then, William Kunstler, were to represent Ferguson until he fired them. Ferguson refused to take his lawyers' advice of an insanity plea, Kuby said.

"The trial gave Colin Ferguson many of the things that he always longed for and eluded him," Kuby recalled. "He was center stage, and everyone was paying attention to what he said."

Kuby said Ferguson adopted a "black rage" defense because racism pushed him over the edge.

"Had Colin been white and the same person, he would have not been OK," said Kuby. "But I don't think it would have come to this."

Giugliano works as an electrical estimator now. Sometimes his job requires a trip to Manhattan. He always drives, as the train isn't an option.

"It's just not comfortable," he said.

But the anniversary is no longer a day of dread. His step-granddaughter Savina was born that same day two years ago. And just last week, he welcomed his first grandson: Santino Francisco.

Details on the charges in body-parts case ... Gilgo-related search continues ... Airport travel record ... Upgrading Penn Station area