'New York Homicide' host Robert Boyce, retired NYPD chief of detectives, calls Long Island home

Robert Boyce, left, on the set of "New York Homicide," with key grip Kyle Noone. Credit: Oxygen Media/Ralph Bavaro

It was like Robert Boyce — a celebrated NYPD chief of detectives — had never left the force.

Here was an IBM electric typewriter, like the one he had pecked on so many times; there was a gunmetal desk, like the ones detectives sat at day after day; and all around were cubical walls painted baby blue, just like the ones he knew so well after 35 years on the job.

Boyce, 68, was not in a precinct squad room but on his new beat — a film set where he narrates his hit Oxygen show, “New York Homicide.”

Boyce is the creative force and host for the true-crime program, digging up cases with lots of twists and turns, from the ones that got scant media attention to the stories that gripped his heart. As a show producer, he also asks detectives and victims’ families to go on the program and accompanies the production team to the old crime scenes.

“It is not policing,” the retired chief, who lives on the North Fork, said of his television career. “It doesn’t have the rigorous regimen, intensity or strategic planning of active investigative casework. Nonetheless, it is satisfying to see and speak of ensuring justice.”

LIFE AFTER POLICE WORK

Life after a career in policing has been good, Boyce said, from his gig as ABC News’ on-air police expert to his marriage in March to a retired detective, Teresa Leto.

And “New York Homicide,” which debuted last year and airs at 9 p.m. Saturdays, has become the most-watched new series in recent years for Oxygen, according to NBCUniversal Television and Streaming, the cable channel’s parent company.

The first season had 12 episodes, but for the second season, which started June 10, the network ordered 20 episodes.

The cases reflect Boyce’s breadth of NYPD service, from early on around tony Central Park to later in the city’s toughest neighborhoods. The only homicides Boyce won’t pitch are those of children and police officers killed in the line of duty. Also, if victims’ families object, the show’s team drops the case.

“We don’t want to pull the scab off,” he said.

Photography director Vitaly Bokser on the set of "New York Homicide," with Robert Boyce on camera. Credit: Oxygen Media/Ralph Bavaro

In the show, the city is on display: A search for a violinist ends in the ventilation shaft of the Metropolitan Opera House. Someone throws the body of a young Long Islander out of an Upper East Side apartment owned by the “jeweler to the stars.” A subway train in Brooklyn is the last stop for a fatally-shot retired cop.

“New York itself becomes a character and brings the diversity of the communities there to the forefront,” said NBCUniversal executive vice president Rod Aissa.

Boyce says he tries to put in as much “New York-ese” as possible, including the accents and employing the language of cops.

For example, detectives solve “mob hits,” not “Mafia hits,” he says. Instead of the “Seventy-fifth Precinct,” say it like NYPD officers do: “Seven Five Precinct.”

FIGHTING ANTI-COP FEELING

Boyce, who retired in 2018, has a mission to counteract anti-police sentiment. Through “New York Homicide,” the retired chief wants to educate the public on how homicides are solved — days of working nonstop without sleep, lack of witnesses and times when “God walks into the case” to help.

“You don’t go home at night, and not only that, when you do go home . . . you’re thinking about it the whole time when you’re at home with your family,” he said. “This is the type of thing I want to show on TV,” Boyce said.

In a case close to his heart, an episode this season details the arrest made in the death of jogger Karina Vetrano, 30, who was beaten and strangled in a park in August 2016, her body found by her father near her Howard Beach home.

The department was accused of bias when Black men in the community were swabbed for DNA after genetic material under Vetrano’s fingernails indicated her attacker may have been Black.

The department also came under fire for the arrest of Chanel Lewis, whose DNA matched samples found on Vetrano’s body and on her phone. His attorneys claimed police racially profiled him and that the DNA was improperly collected.

Boyce said all the men in Vetrano’s life were swabbed for DNA early in the investigation and they were white. When no surveillance cameras in the area showed any man exiting the park toward Queens, he said, they asked for DNA from Black and white men arrested on the Brooklyn side. Lewis was one of them.

His first trial ended in a hung jury. He was found guilty in a second trial in 2019.

“The science and DNA are not biased,” Boyce said. “This was a great, great case because it had nothing to do with human error. It had everything to do with modern technology and DNA.”

Another episode looks at the case of two lesbians attacked in their Brooklyn home in 1995. Detectives for months suspected the survivor of fatally shooting her lover when her account was seemingly unsupported by the evidence. She was later cleared when police arrested a man months later, after he had committed more crimes.

The case exacerbated tensions between the LGBTQ community and the NYPD, but Boyce said it led the department to create an LGBTQ outreach unit.

“You miss certain things that you wish you hadn’t,” Boyce said. “You learn from that and you go forward,” Boyce said.

FINDING HIS PASSION

Growing up in Bethpage as one of eight children, Boyce worked as a bouncer and bartender but was drawn to policing by shows like “Kojak” and movies like “The French Connection.”

“I thought a police career would be exciting,” he said.

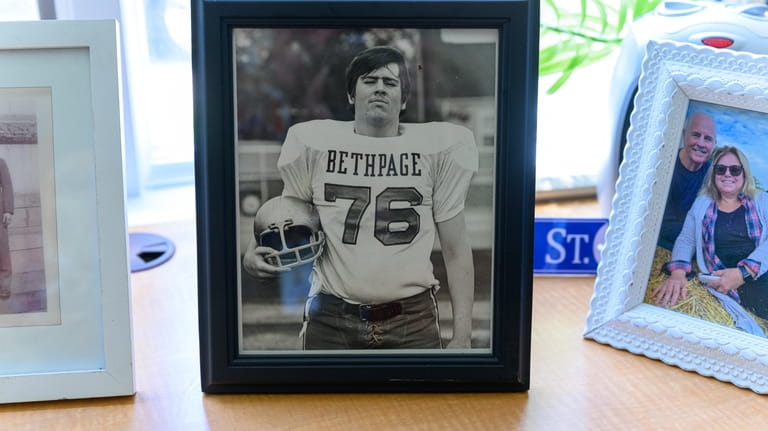

Robert Boyce played football at Bethpage High School before joining the NYPD. Credit: Tom Lambui

At 27, he was one of the academy’s older cadets, but he said his work experience gave him communication skills and street savvy that can’t always be taught.

From Bethpage to the big city was nonetheless a culture shock. At the start of the crack cocaine epidemic, he remembers seeing some white stuff in a vial on the streets for the first time and asking his partner, “What is that?”

Two years into the job, Boyce saw his first body — a woman inside a trash bag against a wall of Central Park.

Detectives were called, but Boyce was already thinking to himself, “They’ll never solve it.”

The next morning, he was amazed that detectives had already made an arrest.

“I was so intrigued that I then thought, ‘This is how I’d like to spend my career,’ ” Boyce said.

Boyce served in city neighborhoods including Brownsville, the South Bronx and East New York. He spent time as inspector of the 67th Precinct in Brooklyn, deputy inspector of the 40th in the Bronx, deputy chief of the gang division and commanding officer of detectives in Manhattan and also the Bronx.

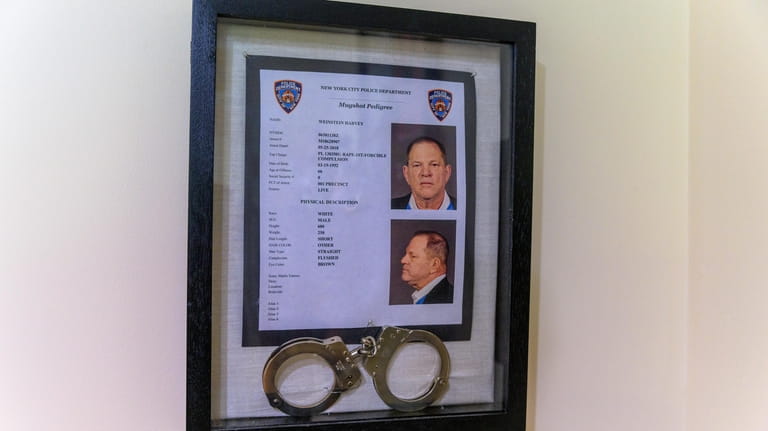

In 2014, then-Police Commissioner Bill Bratton made him chief of detectives, placing him in command of 5,800 detectives. He oversaw major cases, including the 2014 fatal shooting of two officers, Wenjian Liu and Rafael Ramos, in their patrol car; the sexual assault allegations against Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein; and the killing of 6-year-old Prince Joshua Avitto, who was fatally stabbed in a Brooklyn public housing elevator.

Mugshots, mugshot pedigree and handcuffs used when Harvey Weinstein was arrested are dislplayed in Robert Boyce's home office. Credit: Tom Lambui

In a major reorganization in 2016, Boyce took investigative functions that had been under patrol borough commanders and placed them under investigative commanders.

According to NYPD data, major felonies dropped from more than 111,000 in 2013 to under 96,000 in 2018, when Boyce retired.

Bratton, who left the NYPD in 2016, said of Boyce: “He put in the right people in the various forces doing the investigations and demanded the best of them. He was one of the best, if not the best, chief of detectives the department ever had.”

Friends said Boyce earned the loyalty of many in the department and in the community.

“Boyce has the heart of a good clergyman and the grit of a tough cop,” said Robert Mladinich, a retired NYPD detective who befriended Boyce when they were cadets.

When Boyce reached 63, the department’s mandated retirement age, he didn’t want to leave.

At the time, officials at ABC News moved to hire him as a consultant but were told to hold off because police brass were searching for a way around the retirement mandate, an effort that ultimately failed, said Josh Margolin, the network’s chief investigator.

With his police career over, Boyce started at ABC News and then, in 2019, a television production company approached him about a show on female cops juggling work and family.

He traveled to Los Angeles to pitch Oxygen network officials, who initially seemed uninterested, recalled Leto-Boyce, his wife, who went with Boyce as an example of the show’s premise.

But when Boyce started talking about Vetrano, they started paying attention.

Boyce’s retelling of the case made the cable representatives want more, said Leto-Boyce, who worked with Boyce when she was a detective in Brooklyn’s 67th Precinct and he was the inspector.

“When he told that story, they saw how it hurt him,” she said.

Robert Boyce and his wife, Teresa Leto-Boyce, who retired as a retired detective with Brooklyn South Homicide Squad, at their North Fork home. Credit: Tom Lambui

Five years after retiring, Boyce remains committed to police work. He attends police functions and keeps up to date on policing methods.

“He likes talking about cracking cases, new technology that cracks cases, old cases that he had to deal with where things were difficult,” says Margolin.

Boyce is considering writing a book on urban policing, but juggling his television work with active toddler grandsons has been a challenge.

He laughs when he tells people he’ll work “two more years and that’s it.”

“I enjoy the relevance I didn’t expect to have,” he said.

When NYPD Commissioner Keechant Sewell announced her retirement, Boyce chuckled at the thought of applying.

“No, no, no. I’m very happy with what I’m doing right now,” he said. “But if they asked me to be the police commissioner, I would say yes because I love the job too much. It’s the NYPD, the mother ship, they call it.”