Before Beyoncé and J. Lo, the Hamptons' 'first superstar' was Thomas Moran

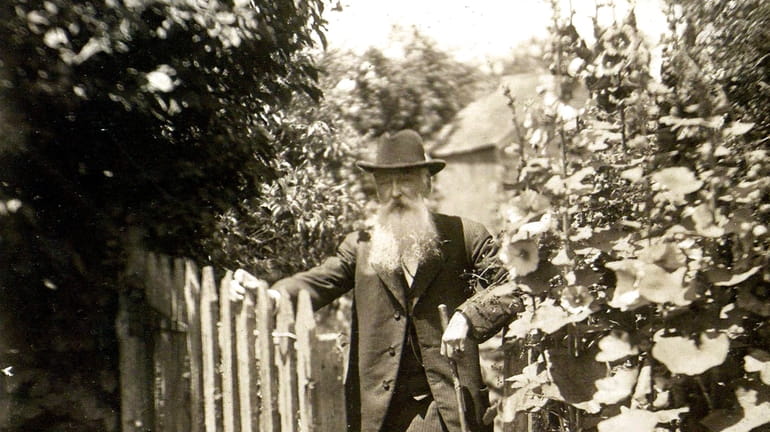

Thomas Moran in the garden of his East Hampton home. Credit: Long Island Collection, East Hampton Library

On a spring day in 1878, a group of men clad in fashionable London walking boots and carrying sketch pads, easels and cases filled with paints and brushes ambled off a train at Bridgehampton, then the easternmost stop on the Long Island Rail Road. They had come from New York City to visit the sleepy, rural outpost of East Hampton because they’d heard about its powerful natural attractions.

The group of 11 shared something in common: They were New York City-based painters and illustrators with a common interest in decorative arts — pottery, glass, textiles. Hence, the name of the association they had formed: Part professional organization, part college fraternity, it was dubbed “The Tile Club.”

But they weren’t looking for ceramic tiles to paint in the Hamptons. The members of the club had been encouraged by Scribner’s, a popular literary and arts magazine, to take a sort of artistic field trip to the boondocks of Long Island. A handful of artists and writers had started visiting the area in the years before the Civil War and word was filtering back about its many charms. The magazine thought a first-hand report on this place by the intrepid Tile Clubbers would prove entertaining.

It certainly proved significant for the history of East Hampton. Because after that trip, the members of The Tile Club were eager to report back not only to their editors at Scribner’s but to one of their most prominent artistic colleagues: Thomas Moran.

At age 41, Moran was already among the country’s most well-known landscape artists. The epic canvasses he had painted of the West, which he had seen during several expeditions in the early 1870s, had given Americans a better sense of the remarkable natural wonders within the far borders of their nation. A decade before the advent of motion pictures, his vivid, colorful paintings conveyed in a way that no other medium then could the majesty and scale of a place few non-indigenous people had visited.

Thomas Moran's "Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone." Credit: National Parks Service

Moran’s paintings of Yellowstone, the Grand Tetons and other now-familiar Western landmarks were also viewed by members of Congress and President Ulysses S. Grant. Some of these images — including his seven-foot-high, 12-foot-long masterpiece, “Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone” — were purchased by the federal government and provided the impetus for legislation that would eventually produce the National Park System.

Thanks to the enthusiastic reports of The Tile Club, however, the painter of the West was now turning his gaze East. In the summer of 1879, Moran and his wife, Scottish-born illustrator Mary Nimmo Moran, rented rooms in a local boarding house and began to explore the pastoral beauty and oceanic majesty of the Hamptons.

A PLACE TO LIVE AND PAINT

Founded two centuries earlier, the village of East Hampton had a population of roughly 600 at the time of the Morans’ arrival. It consisted of a single grassy street, around which were clustered a number of old saltbox houses. The Morans’ daughter, Ruth, later recalled the last leg of the journey, from the rail terminus at Bridgehampton in a stagecoach — “Seven sandy, woodsy miles in a knife-box stage, smelling of leather and hay” — and her initial impressions of the village, in which they arrived at dusk. Ruth recalled the “sweet smell of fields, of growing things with the salt downy fog dripping from the blackness that was East Hampton’s night.”

The Morans marveled at what they found: They were awed by the elms, chestnut and maple trees that shaded Main Street; charmed by the flocks of geese and cows that roamed the lanes around the village; and dazzled by the sun-dappled fields. For Thomas, who was born in Lancashire, England, it all seemed familiar. “East Hampton so resembled a peaceful English village that it won Thomas’ heart at once, and filled him with nostalgia,” wrote biographer Thurman Wilkins.

“I think he found a place that really spoke to him and Mary,” says Nancy K. Anderson, chief curator of American and British art at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. “I think he quickly realized the kind of life he could live there.”

Here was a place in which he could live, breathe, socialize and interact with other artists —while painting a wide array of landscapes and seascapes.

Thomas Moran alongside the fence of his East Hampton home and studio. Credit: Courtesy of the Long Island Coll

In 1883, after spending several summers as renters in East Hampton, Thomas and Mary decided to build a home in the village. In doing so, they can lay claim to being the first leaders and luminaries of what became known as The Summer Colony period of the village, in which artists and writers began spending the warm months here, enjoying the East End’s natural vistas as well as the vibrancy of its emerging social scene. They often mingled with wealthy, Gilded Age New Yorkers who were also making the trek to East Hampton, as well as nearby Southampton and Sag Harbor.

It was, in essence, the beginning of what we now know as “The Hamptons” — a resort area synonymous with pristine beaches and deep pockets, and a place that has attracted artists and entertainers, from Beyoncé and Jennifer Lopez to Andy Warhol and Jackson Pollock since . . . well, since the Morans arrived.

“There is no question, he is East Hampton’s first superstar,” says Mary Mallios, an educator with the East Hampton Historical Society. “You can really trace the presence of the arts and celebrity scene here directly to Thomas and Mary.”

‘QUIRKY’ STUDIO AND HOME

And now, after years of work to restore it to the way it was when they lived there, the Morans’ home studio on Main Street has been acquired by the historical society, becoming one of five historic properties that it manages and interprets. Described as a “quirky, Queen Anne-style studio cottage,” the home is a National Historic Landmark and a member of the Historic Artists’ Homes and Studios Program of The National Trust for Historic Preservation.

The crowning touch of the restoration of the Thomas & Mary Nimmo Moran Home and Studio, built in 1884, was the addition of one of Moran’s paintings — donated to the historical society in November — which has been placed where it hung when the family lived there.

The painting, “Ulysses Deriding Polyphemus (1862)”, hangs above the fireplace at the Thomas & Mary Nimmo Moran Home and Studio in East Hampton. Credit: Gordon M. Grant

“The Morans were important in part because they built the first full time art studio here,” says East Hampton village historian Hugh King, director of the nearby Home Sweet Home Museum. “Other artists would stay for a short time and leave. The Morans stayed.”

And they created art. Moran produced more works of East Hampton and Long Island than he actually did of the West. But “his reputation rests on his Yellowstone and Grand Canyon images,” says Anderson, who is also the author of “Thomas Moran,” an illustrated 1997 book that surveys his work.

Mary was a significant artist in her own right: One of the pre-eminent illustrators of the time, 19 of her etchings — including a number of Hamptons scenes — are today in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Of course, it wasn’t all work for the Morans. Thomas, Mary and their three children — Ruth and an older sister and brother — played tennis on courts laid out among the apple orchards near the house. They went on rambles through the pastures and fields. They even purchased a gondola and went paddling around Goose Pond. The Morans also held literary readings, musical performances and costume parties at their home. “They were big entertainers,” chuckles Steve Long, executive director of the East Hampton Historical Society. “They always had friends coming over.”

Mary Nimmo Moran is seen inside the family’s gondola, which they bought in Venice and used to ply the East End’s waterways. Credit: Courtesy of The Mariners Muse

OTHER ARTISTS FOLLOWED

Following the Morans came a flood of artists. By 1890, there were sketch clubs and painting lessons being conducted around the village, and much of the rest of the East End. “Portable easels and sunshades punctuated the fields and farmyards,” wrote Helen A. Harrison and Constance Ayers Denne in their 2002 book, “Hamptons Bohemia.”

Thomas and Mary led the charge, plunging regularly into the surrounding countryside, pads and pencils in hand, to sketch verdant fields and turbulent seas, lighthouses and old farmhouses, sunsets and sunrises. One of Thomas’s most well-known Long Island paintings, “The Much Resounding Sea,” captures the force and majesty of a huge wave breaking on what is now called Main Beach in East Hampton.

The idyllic Hamptons life ended for the Morans in the wake of the Spanish-American War. In 1898, epidemics of infectious disease swept through American troops returning from Cuba. They were ordered to quarantine in Montauk. While the War Department belatedly raced to mobilize medical personnel and construct adequate sanitary and hospital facilities for the troops, local residents stepped in to help — inadvertently spreading disease into the general population. It was during this time that Ruth contracted typhoid fever. Her mother nursed her daughter back to health but in the process caught the disease herself.

Mary Nimmo Moran died from the fever in 1899. She was 57.

Thomas was devastated. “I think it became very painful for him to be in East Hampton after Mary died,” says Anderson. “My hunch is that their years there together were the happiest period of his life.”

THE NEW CENTURY

While he maintained his home in East Hampton, Moran spent much of the new century traveling. Sponsored in part by the Santa Fe Railroad — which used his bewhiskered image in its advertisements — Moran moved to California. With Ruth taking the role of his assistant and caregiver, he lived for another quarter century, dying in Santa Barbara in 1926. He was 89 years old.

Moran’s body was returned to East Hampton, where he and Mary are buried today in South End Cemetery. Ruth Moran also returned and lived in the house her parents had built until 1947.

By then, a new group of artists was arriving in the Hamptons. Impressionists like Pollock and Lee Krasner, and later pop artists such as Willem de Kooning, Roy Lichtenstein and many others, were finding some of the same inspiration in what painter Edwin Albee called the “intensely beautiful” light, land and sea vistas of the East End — not to mention the stimulating, convivial interaction with a community of artists.

Just as Thomas Moran had.

“It takes one artist to find beauty and the rest will follow,” says Mallios. “And that’s what happened here. Thomas and Mary made East Hampton a destination for artists, and it still is.”

ULYSSES COMES HOME

In 1862, Thomas Moran — who was born in Lancashire, England, but immigrated to America as a boy — booked passage to England.

He was returning on a voyage of self-enlightenment. Moran, then in his 20s, wanted to see first-hand the works of the artist he idolized, Joseph Mallord William Turner. “Any substantial study of Turner’s color technique,” wrote Moran biographer Thurman Wilkins, “required one to seek out the original paintings.”

Moran spent months studying the works of Turner (who had died in 1851). The man who would, a decade later, paint dazzling scenes of the American West was profoundly influenced by the master.

“His debt to Turner included much he had learned about color and light,” wrote Wilkins.

As a tribute to the mentor he had never met, Moran decided to replicate one of Turner’s paintings: An 1834 depiction of a mythical scene in Homer’s Odyssey, in which Ulysses saves his men from the cyclops Polyphemus by tricking and then blinding the monster. Moran created a meticulous copy of Turner’s painting, which was titled “Ulysses Deriding Polyphemus.”

“The work,” says Nancy K. Anderson, chief curator at the National Gallery of Art, “is both an homage to the artist Moran admired above all others and a student work in the time-honored practice of copying paintings in order to learn an artist’s technique.”

Moran’s exercise was widely applauded in London. He was himself so inspired by the painting — particularly the luminescent sky, a Turner trademark — that, when Moran moved to East Hampton in the 1880s, he kept it on the wall of his studio.

Now, more than 160 years since his artistic pilgrimage to England, Moran’s homage to J.M.W. Turner is back in his house in East Hampton. It’s the finishing touch of a $4.75-million dollar, decade-long process to stabilize, restore and interpret the house led by East Hampton Historical Society’s former executive director, Richard Barons, and historical preservation consultant Bob Hefner, as well as the current historical society leadership. A not-for-profit organization formed by supporters of the project helped lead the fundraising effort.

“We hung it above the fireplace in exactly the same spot that Thomas Moran placed it for his daily inspiration,” James Blauvelt, a member of the historical society’s board of trustees, said of the painting.

The artwork was donated to the historical society in November by East Hampton resident Annette Cumming, who had purchased it with her late husband, Ian, some years earlier. She believes that, after having gone through various private collectors, Moran’s Ulysses painting has at last reached its destination.

“I always felt it should end up here,” she said. “It just makes sense that it should be back in his home.”

Tour the house

The Thomas & Mary Nimmo Moran Home and Studio, 229 Main St., East Hampton, can be visited through guided tours. Admission is $12 a person. For a tour schedule, visit the East Hampton Historical Society’s website, easthamptonhistory.org

-calendar, or call 631-324-6850.