Long Islanders talk about staying creative during the pandemic

Denis Ponsot with one of his paintings at a show before the pandemic hit. Credit: Denis Ponsot

If COVID-19 has taught us anything, it’s that life is filled with unpredictability and challenges. It is not a bowl of cherries.

Denis Ponsot, a painter who has exhibited his work in Nassau and Suffolk counties and taught for more than two decades at the Art League of Long Island, knows that. During the “pause” however, he still chose that vividly fruity, vibrantly cheerful subject for his students to create in his virtual watercolor class that launched this year at the Art Guild of Port Washington.

“I’ve been making it a real point to find subjects that will work for people in a positive way,” said Ponsot, who lives in Queens Village, a (cherry) stone’s throw from Nassau County. “That was my thinking. I wanted them to smile and be distracted for a minute.”

Denis Ponsot's "Life Is a Bowl of Cherries" was the theme for a pandemic-inspired watercolor class. Credit: Denis Ponsot

Or 180 minutes. During the three-hour interactive class, Ponsot and his pupils painted the still life, which was based on one of his old photographs. Chubby red cherries. A homey blue bowl. A background the shade of sunshine. A bold, multihued swash, Ponsot said, “to add energy and a sense of moving forward.”

Forward motion typically tolls thematically — even more so in a pandemic. Other recent Ponsot paintings reflect similar optimism, including one of Old Westbury Gardens in colorful, life-goes-on bloom. And there’s Caffe Reggio, a New York City spot in Greenwich Village that he associates with sweet, warm memories — and cups of cappuccino. “It’s a response to times we’re living in,” Ponsot said.

And what times they are. Four months into the pandemic, Long Island painters, authors and musicians — some who are household names, others who aren’t as well-known — are reacting to the COVID crisis in varied creative ways. The uninvited virus has become a serious motivator compelling them to pick up a paint brush, open a laptop, pick up an instrument and to make the most of the precious commodity of time.

"The pandemic forced itself into the novel I'm writing," said bestselling mystery author Susan Isaacs. Credit: Linda Nutter

Weaving a real virus into a mythical town

“The pandemic forced itself into the novel I’m writing,” said bestselling mystery author Susan Isaacs, whose books stretch back to “Compromising Positions” in 1978. “To ignore it would have put the book in some mushy, timeless place. So COVID-19 is there, but it’s in the background.”

The Port Washington author is currently at work six days a week on “Bad, Bad Seymour Brown,” her 15th novel and a sequel to last year’s “Takes One to Know One.” The story follows further exploits of Corie Geller, an ex-FBI agent who lives with her husband, a federal judge, in a sprawling house in the “mythical town of Shorehaven,” said Isaacs, 76. “It’s a combination of Port Washington, Manhasset and Roslyn.”

Corie’s father, a former NYPD detective who suffers from depression, and mother, an actress, arrive from New York City amid the COVID crisis. “What the pandemic has done is give me a way to have the family tight together,” Isaacs said.

Quicker than you can say, whodunit, Corie and Dad team up to discover why a film studies professor was marked for murder. The puzzle leads to a cold case important to Corie’s father.

“It opens up a whole new relationship for Corie and her father,” said Isaacs. “She and her dad are already great pals, but they become even closer by working side by side.”

Musician Thomas Manuel created a piece called "Flump" during the pandemic. Credit: Peter Coco

Making music with a healing message

Thomas Manuel, 41, a trumpet player, jazz historian and music professor at Stony Brook University, adores engaging with his students in a classroom. Playing alongside fellow musicians is another comfort zone. “I’m a people person,” he said.

Coronavirus isolation soon left him feeling “stripped. I wasn’t teaching or playing music in person,” he said. “I thought, ‘This is about the lowest things can get.’ ” That tickled a memory of the late American jazz bass player Milton Hinton, who had his own term for the lowest point — “fump.”

Manuel’s riff on that, “Flump,” is an upbeat piece composed during social distancing and recorded at The Jazz Loft in Stony Brook, which he founded four years ago for music preservation, education and performance. “Freedom,” a meditative musical answer to far-reaching unrest that nods to “Take the A Train” composer Billy Strayhorn, is another new composition. Manuel premiered the work at the remote eighth-grade graduation in June for the Harbor Country Day School.

“Jazz is a healing type of music,” said Manuel, who lives in Port Jefferson. “When something bad happens our reaction is to create something that can serve as a healing force. I’ve written more in the past three or four months than ever. Part of it is having the time. This is an unprecedented complete stop.”

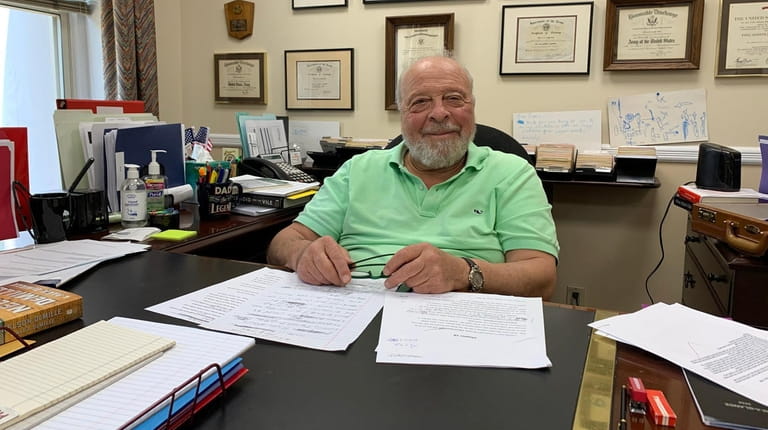

Author Nelson DeMille, of Garden City, says the pandemic has increased the amount of time he spends working. Credit: Dianne Francis

Losing oneself in thought with an extra-soft lead pencil

Bestselling novelist Nelson DeMille has already put a pandemic in a page-turner — in 1997 in “Plum Island,” which introduced former Det. John Corey. The author of more than 20 thrillers and spy novels has no plan to retrace narrative steps and discourages other writers from going the COVID-19 route. “It’s been done,” he said. “We’ve lived it — and still are living it.”

Amid the current viral crisis, DeMille, 76, who lives in Garden City, has been busier than ever. “I’ve become much more productive,” he said. “Normally I would knock off work around 5 or 6 o’clock. Now I’m working seven days a week, putting in 12-hour days without interruption.” Midway through a new John Corey adventure — it seizes inspiration from the Gilgo Beach murders — DeMille said the coronavirus has provided plenty to think about. But that’s all back-burnered when he works.

“I go into a zone when I write,” he said, adding that he still works in longhand with a very soft No. 1 lead pencil. “I’ve got to shut out the outside world. I have to get lost in the world of the book.”

Huntington playwright Jack Canfora, with his dog, Daisy, wonders what kind of plays people will want to see once they can go to the theater again. Credit: Sally Klingenstein Martell

Dramatizing connections — and the lack of them

Family tensions tend to reverberate in dramas by Huntington playwright Jack Canfora, including “Place Setting,” a story of secrets and lies presented in 2007, and “Jericho,” a play about a holiday gathering that premiered four years later.

Like everyone connected with theater, Canfora, 51, who taught English at Plainview-Old Bethpage JFK High School for 12 years, asks himself the same two questions at least once a day. “One is, when will plays be done again?,” he said. “The other is, what kind of play is going to be interesting for people to watch.”

Time will tell on the first query. As for the second, Canfora is certain people won’t want to sit through a COVID-19 drama. “I would never be inclined to write about current events while they’re still current,” he said, adding that isolation has “magnified issues that I wrestle with about the ways people connect and build a community — or fail to do so.”

Those themes loom large in his in-the-works family drama as well as in “Zoe,” a one-act written in April about a divorced couple’s prickly reunion sparked by the fate of the titular cat. “It’s designed to work as a Zoom meeting or a Skype session. With a few adjustments,” he said, “it could move to the stage. When the time comes.”

St. James author Anne Coltman says that initially during the pandemic she was overcome with worry and could not write. Credit: M. Ring

Finding a focus and an escape from fear

St. James author Anne Coltman has written two poetry collections, including “For the Love of Grandma,” in 2009, and two books. When the pandemic hit, Coltman was at work on an anthology. She was looking to add new musings, anecdotes and poems to it.

“It took some weeks to write anything at all,” said Coltman, who grew up in former British Guyana before coming to the United States several decades ago. Between being in the over-65 vulnerable age group and her husband’s double lung transplant, she was overwhelmed with worry.

A Facebook post got her writing again two months ago. “It was a video of New York City at night during the pandemic lockdown,” Coltman said. “It made the city look like an optical illusion — still beautiful and majestic, but I was stricken by the sheer lack of liveliness.”

She flashed back to stories her grandmother told her of Spanish flu and cholera. “I was suddenly plunged into a world that I did not recognize, a world that seemed to resemble the one I only heard about many, many years ago,” she writes in “Is It Granny’s Deja Vu,” a new short essay. “Masked Faces,” a new poem whose title speaks for itself, wonders: “Will the world get back to normal? What normal things are we looking for?”

Coltman doesn’t have answers, but asking questions helps. “The major thing for me was to focus on my writing,” Coltman said. “As soon as I started writing it was like I was in a different environment, away from the worry.”

"COVID-19 has pushed me to get creative about putting my material out there in a different way," says musician and author Patricia Shih, who lives in Huntington. Credit: Deidre Elzer-Lento

Exploring feelings raised by coronavirus

“I don’t write love songs. Since the beginning of my career, my songs have been about issues and social justice,” said Patricia Shih, 67, a Huntington musician, author and artist. “The Color Song,” which she wrote in 1984, questions labels.

“Why do they call you yellow man?,” the song asks. “You’re not yellow at all. Yellow is the color of the morning sun and dandelions and chicken soup and legal pads and fearful minds. Yes, yellow is the color of all these things. But people are not the same.” Shih said she’s been told that her “music is like a can opener of the mind.”

Before the COVID pandemic caused her professional endeavors “to evaporate,” Shih’s work took her to schools, libraries and parks, where her family-friendly shows (“I have 18 different ones,” she said) are designed to entertain and educate. She’s covered such subjects as bullying and nonviolence. Now COVID-19 is top of mind, along with the fear of the unknown it has fostered.

“I keep thinking about isolation and the forced separations. I think of families on the southern border,” Shih said. “I’m not interested in writing about the virus, but how it has impacted our lives and the feelings it has brought up.”

Shih is also keen on expanding how her work is experienced. “My work is interactive. COVID-19 has pushed me to get creative about putting my material out there in a different way,” such as on digital platforms, she said, adding that the pandemic has been motivating and clarifying. “Social upheaval is painful but it can be positive. It makes us examine the status quo and what is working and what is not.”

"Puffville" children's series author Joseph Costa has used his free time during the pandemic to create video versions for YouTube of his live reading presentations in schools, bookstores and libraries. Credit: Joseph Costa

Leaning into different platforms

Rocky Point author Joseph Costa, 56, knows all about flower power. Puffs, colorful characters in his nine children’s books including “Welcome to Puffville,” actually emerge from blossoms. In his stories, they instruct kids about the value of inclusion, teamwork and other values. “I like to include lessons but subtly,” said Costa, who is part of the security team at Ridge Elementary School.

Costa has used the pandemic to work on new books — Puffs go international! — and to create video versions for YouTube of his live reading presentations in schools, bookstores and libraries. “Families can enjoy them in the safety of their own home,” Costa said. “Before the pandemic, I’d never thought about doing that.”

Huntington painter Joyce Kubat, standing in front of her work, says, "I can't be worried about something and do artwork at the same time. When I do artwork my mind enters a different place." Credit: Joyce Kubat

Making fragments from the past and time matter

For Huntington painter Joyce Kubat one impact of COVID-19 can be measured in terms of artistic productivity. “I’ve done about 50 oil-on-wood panels since the pandemic began. They’re small,” she said, adding that she would not “have done any of that had it not been for” COVID-19.

Identity has been a recurring theme in her work. Her new panels, which depict faces, hands, bowed bodies and skulls, borrow fragments of art she made in the early 2000s. Kubat, who has exhibited her work throughout Long Island, had a show set to open March 9 at Hofstra University that never opened because of the pandemic. The exhibit, she said, “is still scheduled for September if the university is open.”

In the meantime, she’s doing what she loves — making art. “I can’t be worried about something and do artwork at the same time,” Kubat said. “When I do artwork my mind enters a different place.”