U.S. must shift from containment to aggressive mitigation

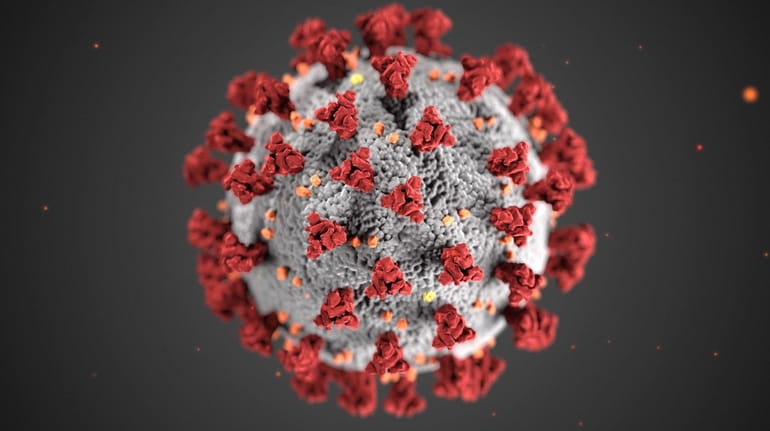

This illustration, created at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), reveals ultrastructural morphology exhibited by coronaviruses. Credit: DCD

The situation with coronavirus has changed dramatically over the last few weeks. We are in the midst of a worldwide pandemic, and the United States will see an even more dramatic escalation in the weeks to come. As communities, institutions and individuals, we need to switch from reacting to what’s happened to taking bold action in anticipation of what’s coming.

Just two weeks ago, there were 15 cases diagnosed in the United States. We have now have more than 1,600. An outbreak in Washington state has claimed the lives of at least 20 residents in one nursing home. In New York, the suburb of New Rochelle went from one case to over 110. There are likely many more clusters that are yet to be diagnosed due to lack of testing capacity.

As the situation becomes much worse in the coming weeks, one major concern is with overwhelming the health care system. A moderate outbreak could result in 200,000 patients needing intensive care, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The United States only has 100,000 intensive care beds, and most are already occupied. If tens of thousands become sick at once, people will simply not receive the care that they need. It will not only affect patients with coronavirus, but also others with heart attacks, strokes and conditions requiring intensive care for survival. In other countries, people have died because they couldn’t access care. We are at risk of that happening in the United States, too.

Hospitals are already implementing their pandemic preparedness plans. They are increasing capacity, canceling routine procedures, ramping up telemedicine and counseling people who can to stay home.

But hospitals alone cannot solve this crisis. It’s up to all of us to decrease the demand for hospital care by reducing the rate of disease transmission. In epidemiology, this is called "flattening the curve." We cannot stop transmission altogether, but we can slow it down. That way, we can reduce the number of acutely ill patients and reduce the likelihood that patients who need care have to go without.

What does this mean? So far, the United States has focused on containment: quarantining travelers and investigating contacts of the ill. As more and more cases are detected, public health agencies won’t be able to keep up, nor would it make sense to. The focus has to shift from containment to mitigation, meaning that instead of stopping individual transmission, the goal is to implement societal interventions of social distancing.

These efforts have already started. The CDC announced new guidance for those most vulnerable to coronavirus (people over 60 with underlying medical conditions) to avoid crowded places and not go on long-haul flights and cruises. Major conferences affecting hundreds of thousands of people are canceled. The governor of Washington has restricted gatherings of over 250 people and Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo banned gatherings of more than 500 people and has established a containment area around New Rochelle. And the two major Democratic presidential candidates canceled rallies, and the next primary debate on Sunday will be held without a live audience.

These are all timely, appropriate and responsible decisions. It’s time for all sectors to implement social distancing measures that are in their control. Many companies have already started telework and canceled nonessential travel. Some jobs don’t lend themselves to work from home, but all those that can should do so. Public meetings should switch to virtual town halls. Universities that haven’t already should change to online instruction, and schools need to weigh the downsides of closure with the risk of children being vectors for transmission to their families and beyond.

To be sure, all of these decisions come with tradeoffs. They will hurt the economy in the short term. But bold actions will save lives. During the 1918 influenza pandemic, Philadelphia held a parade of 200,000 people, while St. Louis shut down schools, theaters and sporting events. The death rate in Philadelphia was double that of St. Louis’, a result directly attributable to St. Louis city officials’ aggressive — if initially unpopular — actions.

Individuals can each do our part, too. Even if the young and healthy may not get very ill, they can still spread coronavirus. Everyone can stay home when sick, cover coughs and sneezes and stop shaking hands. Washing hands frequently makes a huge difference. Together, we can reduce the risk to ourselves and all those around us.

The U.S. is already behind in our response to coronavirus. The time for aggressive action is now, or else will look back and wonder why we didn’t act sooner when we had the chance.

Dr. Leana S. Wen is an emergency physician and visiting professor of health policy and Management at the George Washington University Milken Institute of Public Health. She wrote this piece for The Baltimore Sun.