Biden's amnesty won't attract new waves of immigrants

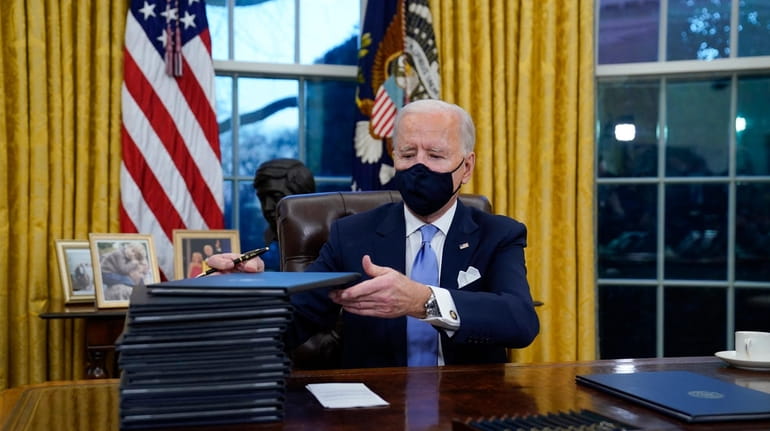

President Joe Biden signs his first executive orders in the Oval Office of the White House on Jan. 21, 2021. Six of Biden's 17 first-day executive orders dealt with immigration, such as halting work on a border wall in Mexico and lifting a travel ban on people from several predominantly Muslim countries. Credit: AP/Evan Vucci

The centerpiece of President Joe Biden's broad proposal for immigration reform is an eight-year path to citizenship for unauthorized immigrants. This would be the boldest amnesty since Ronald Reagan signed the Immigration Reform and Control Act in 1986. It's also likely to prompt the same fear: that fresh waves of immigrants will be inspired to cross our southern border illegally in the hope of future legalization.

Most studies conclude that about 11 million undocumented immigrants are living in the U.S. A few argue that there are about twice that number. But what all the studies agree on is that the unauthorized population has been falling since 2007.

Critics and skeptics of Biden's path to citizenship will have one big question: Will amnesty cause this trend to reverse? Will the U.S. once more be flooded with millions of undocumented immigrants who believe they'll eventually get an amnesty of their own? And won't that leave the U.S. right back where it started, with a huge population of residents forced to effectively live underground, subject to exploitation by employers who ignore labor laws?

Reagan's legalization campaign has often been accused of doing just that. In fact, though, it probably didn't. Illegal immigration briefly surged in 1986 (probably in anticipation of the amnesty), but after that it fell modestly for several years before resuming its upward climb in the late 1990s. Researchers have generally concluded that Reagan's reform, which also included a substantial increase in immigration enforcement, actually reduced illegal immigration modestly.

Upon reflection, it makes little sense that such legalization programs would draw a wave of new unauthorized immigrants. If Biden's bill passes this year, it will have been 34 years since the last amnesty. Who would move to a country in anticipation of decades of living underground and working crappy jobs, just for the chance they'd get to start on a path to citizenship some 30 years down the road?

In fact, there are even bigger reasons to argue that a new amnesty won't bring an influx of people across the border. The first is that Mexico — historically the primary source of unauthorized immigrants — has a much lower fertility rate now. Back when Reagan granted his amnesty, the typical Mexican woman could expect to have four kids over the course of her life. Now that's down to about two.

Fewer kids means fewer excess people to send north in search of work. It means young Mexicans will need to stay home to care for aging parents and take over family businesses.

Also, Mexico's economy is now much richer than it was in Reagan's time. In terms of purchasing power parity, its per capita GDP is more than $20,000, almost half that of the U.S. That's not quite a developed country yet, but no longer a poor one either, and well past the point where emigration tends to fall off.

So immigration pressure from Mexico is decreasing. But conditions in the U.S. have also changed. The kind of construction jobs that many unauthorized immigrants worked in the 1990s and 2000s are much less available. Multiple initiatives to increase border enforcement, including the Secure Fence Act of 2006, have made the border much harder to cross. Bill Clinton's 1996 welfare reform law denied many government benefits to undocumented immigrants. And that's in addition to the creation of a dedicated Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency, and a generally stricter apparatus of internal immigration controls.

So where Mexicans in Reagan's day looked north and saw a welcoming land of opportunity across a generally unguarded border, today America feels like a much more forbidding country.

That's why the only significant source of migrants crossing the U.S.-Mexico border is now a handful of violent and impoverished Central American countries: Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador. These are the sources of the "caravans" of asylum seekers that periodically grab headlines, and which Trump worked so hard to stop. Illegal immigration from Central America is fairly modest, but it does exist.

It's possible that a Biden legalization program would encourage more caravans from Central America, but it seems unlikely. These people's first and foremost hope for immigration to the U.S. is asylum, not illegal immigration, and amnesty doesn't affect the asylum process. Meanwhile, fertility is falling in Central American countries as well, while their economies are growing. And all the factors that make the U.S. a less attractive destination than it was 20 years ago apply to Central Americans as well.

So a Biden amnesty is not likely to bring a new flood of illegal immigration. Barring a climate disaster or other catastrophe that creates masses of refugees, people simply have far fewer reasons to cross the U.S. southern border now. The big wave of Latin American immigration is over.

Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.