Navarrette: The Mexican reverse migration

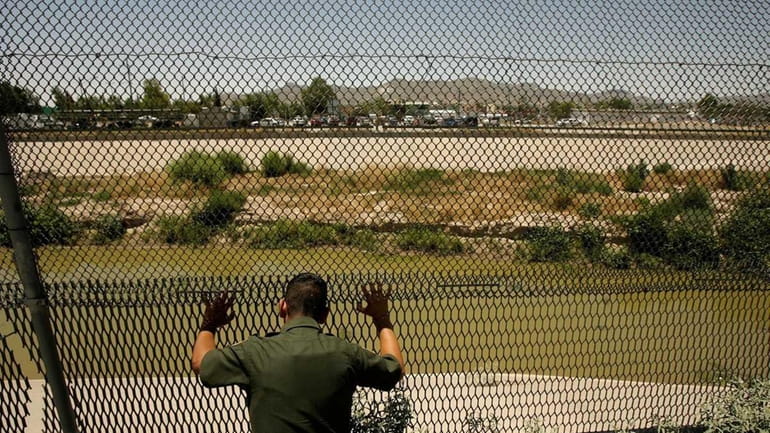

A U.S. Border Patrol agent scans the Rio Grande through a fence after seeing four people attempt to cross the U.S.-Mexico border illegally (June 26, 2007) Credit: Getty Images

How long before the smugglers who have made millions helping Mexicans enter the United States illegally figure out that the next big idea is to help them return home?

Researchers at the Pew Hispanic Center report that net migration from Mexico to the United States has slowed to a trickle, and that one of the big reasons is that would-be immigrants have decided their job prospects are better at home. It's only a matter of time before the 6.1 million Mexicans who are already living without documents in the United States decide that opportunity is knocking -- south of the border.

According to the report, the Mexican-born population in the United States, which had been increasing since 1970, peaked at 12.6 million in 2007. It has dropped to 12 million since then. This makes for interesting times in the age-old and codependent relationship between the United States and Mexico.

We got a glimpse of just how interesting back in 2009 when The New York Times reported that more and more Mexican parents were sending money north to help support their children in the United States. Just like their parents and grandparents before them, this generation had trekked across mountains and deserts for the promise of better-paying jobs in the United States that would allow them to send money to their families. But now, they were unemployed and hit hard by the recession, and they were the ones who needed help.

In the last three years, the Mexican economy has shown signs of improvement thanks in part to increased foreign investment from China and other countries and the growth in the manufacturing industry. Mexico had grown much too comfortable depending on billions of dollars in remittances from expatriates in El Norte. This is a good thing. Such dependence killed initiative and hampered the Mexican economy. When the financial crisis hit the U.S. economy, Mexicans were forced to come up with a plan B and create their own jobs. It worked.

A more robust Mexican economy and a lack of jobs in the United States are just two reasons that Mexican migration has tapered off. As the Pew report notes, there is also greater demand for workers in Mexico because of declining birthrates over the last few decades. In 1960, a Mexican woman typically had more than seven children. Five decades later, with more family planning, the number is just over two. Fewer people means less competition for jobs in Mexico, but it also means that the Mexican economy can no longer spare the workers it once did.

Finally, the aggressive immigration enforcement policy of the Obama administration is also a factor. In the last three years, the Department of Homeland Security has deported more than 1.2 million illegal immigrants -- the vast majority of them Mexican. You can be sure that some of those people came right back, but not all. And those who gave up and stayed in Mexico probably warned others not to bother uprooting and seeking opportunity here.

Besides, what many people don't understand is that, for most Mexican immigrants, the preferred model isn't a total and permanent relocation. It's a revolving door where they can come and go across the border to work, but they always have the option of returning home. Every time we build walls and otherwise fortify the border, it discourages this movement.

For those people already in the United States, the idea of leaving -- even when it makes sense economically -- isn't always attractive. After all, if they change their minds, they'll find it difficult to come back. And for those who are thinking about heading to the United States, many will conclude it's not worth the trouble if they're only going to be rounded up and deported when they get here or wind up trapped and unable to go home.

Rattled by changing demographics, Americans have complained for decades that they want less immigration from Mexico. In a few years, as chores go undone and prices go up, they'll be complaining that they want more.

Ruben Navarrette Jr. is a columnist for the San Diego Union-Tribune.