Parents in Uvalde had good reason to expect police to do more

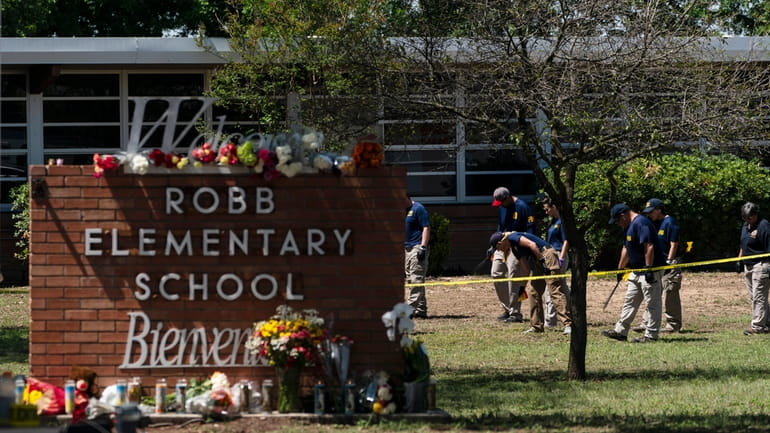

Investigators outside Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, Wednesday. Credit: AP/Jae C. Hong

It's hard to imagine a more righteous anger than that of the parents being kept at a distance from Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, on Tuesday. A gunman was inside the building with their children while police were outside, holding them back. Any parent can explain the often-irrational anguish that comes from being unwillingly separated from their children. That the immediate barrier between them and their kids were police, the people entrusted to keep the kids safe, must have been fully enraging.

What's still not entirely clear is the extent to which that anger was justified. There were police outside, managing the crowd, but there also appear to have been police inside the school. Parents were furious that the police outside weren't acting to protect their families, but they couldn't see what was happening within the school's walls.

We can say with some confidence that the police outside the building may not have been communicating with those parents clearly, given the way the public story about law enforcement's response has evolved since the massacre took place. We can also say with some confidence that the response did not reflect the expectations that residents of Uvalde likely had for their police force.

Again, our understanding of what happened at the scene still contains holes (in part because of the evolving stories from local and state officials). But what we know doesn't comport with how we might expect police to respond to a shooting incident in the abstract.

The shooter, Salvador Ramos, shot his grandmother and then drove to the school, crashing his truck nearby at 11:28 a.m. For more than 10 minutes, he stayed outside the school sporadically firing his weapon. He then went inside without being confronted by any school guards, as had originally been reported.

It's useful to note that the school was only a few blocks from a police station, less than five minutes away. A recurring theme to this discussion is that we should acknowledge that we cannot speak for all of the decisions made by police or know the contributing factors that might have affected the response. But it is not the case that the school was located in some remote, hard-to-access part of the city.

Police arrived four minutes after Ramos entered the school and, according to a state official, tried to engage him. Ten minutes after that, someone recorded video of parents expressing their frustration at the police outside.

Now questions turn to what was happening inside. It wasn't until 1:06 p.m., more than an hour after that video of the frustrated parents was filmed, that police announced that Ramos had been neutralized. What happened in the interim?

Speaking to CNN's Wolf Blitzer on Thursday, an officer with the Texas Department of Public Safety explained one apparent reason for the delay.

Blitzer asked Lt. Chris Olivarez if it wasn't the case that best practices dictated engaging with an active shooter as soon as possible. Olivarez acknowledged that this was correct - and then added a caveat.

"They do not know where the gunman is. They are hearing gunshots. They are receiving gunshots," he said. "At that point if they proceeded any further not knowing where the suspect was at, they could have been shot, they could have been killed and at that point that gunman would have had an opportunity to kill other people inside that school."

He argued that officers effectively kept Ramos contained in one classroom - but other reporting has suggested that Ramos barricaded himself in that room to protect himself from police. The Associated Press reported that police waited for a school official with a key to arrive in order to subdue Ramos.

We can't gloss over Olivarez's other point, though, that officers were wary of moving forward out of the risk of being shot. We should apply the same caution to his presentation of the officers' state of mind as we should to any other second-hand commentary. But if that is true, it's a remarkable deviation from what the public has been taught to expect from law enforcement.

The Uvalde Police Department had a special weapons and tactics (SWAT) team that it promoted on its Facebook page. In February 2020, the department informed residents that it would be "visiting the Uvalde CISD schools, Uvalde Classical Academy, and local businesses throughout the day" in order to "familiarize themselves with layouts of our local schools and businesses." This likely served some utility for the officers but was also a show of competence for the public. As researcher Pete Kraska has noted, though, such units are often less well-trained than one might expect. The vast majority of time in smaller cities, that wouldn't matter; there simply wouldn't be many points at which a well-trained SWAT deployment was necessary.

This divergence between what we expect from law enforcement and the demands placed on them is important. Over the past decade, there's been a surge in public support for police officers, often as a political reaction to questions about law enforcement raised by the Black Lives Matter movement. Americans have understandably been quick to identify police officers as heroes ready to give their lives for the public, an impulse that's been unfortunately intertwined with partisanship. Any indication that police were unable or unwilling to uphold that trust is disconcerting.

Being a police officer involves assuming risk. It means being willing to enter dangerous situations. Happily, though, being a police officer has gotten less deadly over the past few decades. From 1977 to 1981, an average of 212 police officers died in the line of duty on average each year, according to data compiled by the Officer Down Memorial Page. From 2017 to 2021, the average was 170 - excluding deaths from covid-19.

That's as the number of police officers increased, of course. From 2000 to 2005, there were an average of 27 officer deaths per 100,000 police (using occupational data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics), excluding deaths related to Sept. 11. From 2015 to 2019, the average was 20 deaths per 100,000, again excluding deaths linked to 9/11 illness. If we include 9/11-related deaths, the drop was from 30 to 25 per 100,000.

Business Insider looked at BLS data from 2020 and determined the most deadly occupations relative to employment. The riskiest was people who worked in fishing and hunting, followed by logging and roofing. Police officers ranked 18th, just ahead of maintenance and repair workers.

This amplifies the contrast between public expectations and the police response. Uvalde residents were told that the police had an elite group ready to press forward into danger on their behalf and Americans generally have stepped up to defend police as protectors - defending them politically as policing itself has gotten safer thanks in part to consistently increasing public spending on law enforcement.

So those parents were there, outside of the school with the police, while their kids were inside with the shooter. They expected more police to rush in; some parents even floated with the idea of running in themselves. One mother did, according to the Wall Street Journal: after being detained by police, she found an unguarded area and snuck into the building to take her kids out. But what the parents saw was caution they found inexplicable. What an official told Wolf Blitzer is that caution was the watchword within the school's walls, as well.

This was one incident. But the conflict between what we've been told to expect from police, and what we currently understand to have occurred in Uvalde, demands resolution.