Adults talk about empowering young people — only when they get along

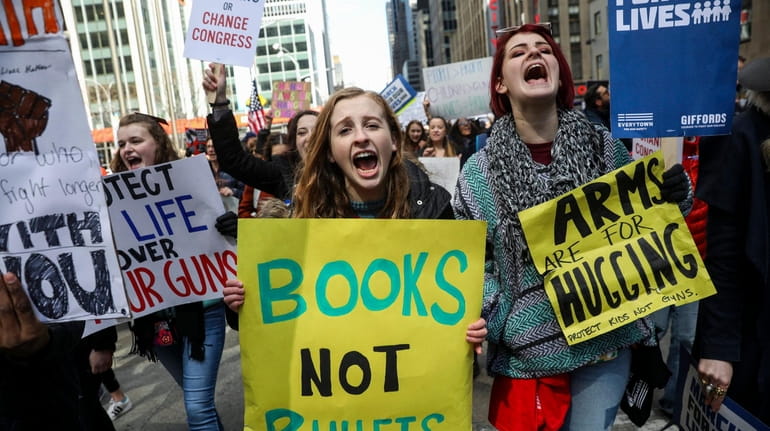

Young people rally against gun violence in New York City. Credit: Getty Images/Drew Angerer

Students across the country, from Minnesota to New York City, have walked out of classes and are taking to the streets to demand better COVID safety policies. Some protesters called for remote learning while others asked that school leaders enforce policies already in place. Students in Oakland, California, started a petition, hoping that administrators would listen. When they failed to, the students walked out.

Adults have routinely been dismissive, even suggesting that students are pawns of teachers' unions or that students simply want to skip classes. The idea that young people can clearly see what is happening at schools during the pandemic — like they have with climate change, guns and the curriculum — has routinely been brushed aside.

But these students are a part of a long tradition of young people who have been told, in the creation of youth civic engagement programs or through a system that rewards participation in student government, that their voices matter. And they are claiming that power now.

The practice of empowering youths to voice their own demands gained momentum in the 1960s as the federal government established "community action programs" to combat "feelings of 'powerlessness' among poor people of color." Initiated as part of Lyndon B. Johnson's War on Poverty, these programs included job training and skills development classes as well as grants for community development to fight poverty.

The emphasis on community involvement also extended to the expansion of parallel civic institutions. The Detroit Commission on Children and Youth, for example, debated the need to establish a citywide youth government in 1965. Although cities like Washington D.C. and Philadelphia had established similar youth programs much earlier, the mid-1960s witnessed a rapid increase in such projects. The programs aimed to teach students the values, ideals and practices needed to live in a democratic society and sought to redirect adolescent energy away from "delinquent" activities.

During the 1960s, Black high school students in Detroit decided to act on the belief that their concerns mattered as future citizens of a democratic society. In April 1966, Charles Colding, a Black student at Northern High School penned a biting critique of Detroit's public schools in The Northern Light, the student newspaper.

He argued that students at Northern received an "inferior education" compared to students at the nearby majority-White Redford. This was not hyperbole. In fact, half of the Black students in the high schools usually dropped out before graduation. And only 20% of those remaining had been prepared to compete with peers from majority-White schools.

As editor of The Northern Light, Colding would have heard adults extol the virtues of student journalism, with advocates claiming it would prepare students for citizenship and demonstrate the "role of the press in a democracy." Yet, despite government proclamations that community voices mattered in local affairs and claims that student journalism prepared youth for citizenship, Colding's actions were met with hostility when he made substantive critiques of education leaders.

When the head of the English department refused to publish the article, Colding and peers Judy Walker and Michael Batchelor organized a student walkout and issued several demands. 2,300 students joined them, igniting weeks of struggle between administrators and the community over the insufficient resources available to Black students. They also demanded the removal of school principal Arthur Carty who had supported the decision to withhold the editorial, and who was White at a majority-Black school. And finally, the students called for the distribution of comparative data on the quality of education at various Detroit-area schools.

School leaders finally listened, but only after students staged the boycott with community support. The organizing garnered some victories, including Carty's removal from Northern and the formation of the High School Study Commission, which would produce data on the quality of education in Detroit's schools.

But the walkout also attracted backlash. Some adults worried that Carty's removal could signal to students that they controlled the schools. The Detroit Free Press called the boycott evidence of a larger issue of "runaway emotionalism" by young people who were being "egged on" by adults. According to Martin Kalish, head of the Detroit Federation of Administrators and Supervisors, "Adolescents can tell a principal how to run a school, back it up with threats, and get their own way." The Organization of School Administrators and Supervisors believed that the boycott would inspire administrators to fight for the right to collective bargaining. Without greater workplace protections, they argued, they would have to bend to the will of adolescents.

Some Detroit residents were horrified to see the Board of Education cede power to students. Some threatened to oppose a proposal to fund schools by raising the millage tax rate on property. One letter suggested that White taxpayers were being asked to pay for the public education of the children of Black Detroiters who received public aid. And now that Black children were making what they perceived as unreasonable demands, they were fed up. Colding's editorial and the display of student power had gone too far.

The event and the backlash it precipitated also revealed why adults refused to listen to young people when they spoke out. Although the students were asking for something fundamental — equity in education — school leaders treated their request with zero urgency. They viewed students as too emotional to make rational decisions and as a threat to authority when they organized collectively.

But the Northern boycott exposed the need to take student demands seriously. Black students' recognition that they were receiving an inferior education was a catalyst for change. Because students took more sincerely the concept of "civic engagement" than perhaps adults wished, they disrupted business as usual and found a way to make the adults around them listen.

Once again, student organizing is on full display in 2022 as students protest against insufficient COVID mitigation measures and shine a light on profound failures in their schools. For example, students in Chicago, from Chi-Rads, called for support around mental health and food insecurity. The podcast "Miseducation," is amplifying students' experiences with educational inequality in New York Public Schools. And while some students haven't staged walkouts, they are still giving voice to deep concerns on social media, making explicit the connection between funding inequity and learning conditions.

Students are also exposing a long tradition of adult doublespeak. Even as school leaders have routinely encouraged students to hone their critical thinking skills and be leaders, they have bristled when students — heeding those calls — voiced opinions that challenged the ways schools operated.

Since the 1960s, educators have expanded various forms of sanctioned youth civic engagement. High school counselors and college preparation programs encourage students to participate in extracurricular activities like community service programs and social and political student organizations, to make themselves more competitive as college applicants.

But students have taken a different lesson from these experiences. When NYC school officials recently invited 25 students to a listening session, the students felt patronized. "As grateful as we are to have student voices at the center of the table, we felt dismissed and sensed some disrespect toward teachers. We're looking forward to our second session and hope student voices are not only heard but acted upon," the group wrote on Twitter. They can see through adult doublespeak and are determined to move leaders from lip service to action.

We have told students that their voices matter when they say what we want them to say and only in the limited forums we prescribe. But taking students seriously means actually listening, even if we don't like what they say. That incoherence says more about the adults in the room than the students. Today, as in the past, when students protest the conditions that make their schools unequal and unsafe, they are demonstrating that they have learned the most important part of the lesson. And for that, we should be grateful.

Dara Walker is an assistant professor in African American studies, history and women's, gender and sexuality studies at The Pennsylvania State University.