Ian McEwan's 'The Children Act': Short and intense

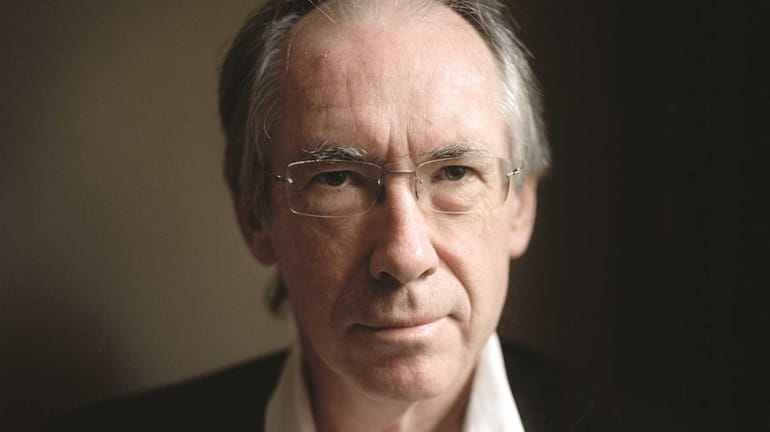

Ian McEwan, author of "The Children Act" (Doubleday, September 2014). Credit: Joost van den Broek

THE CHILDREN ACT, by Ian McEwan. Doubleday, 221 pp., $25.

'The Children Act," like nearly all of Ian McEwan's preceding books, is a tightly focused novel that works out a problem in morality almost as if it were a logical proof. Given these characters and these circumstances, and this decision or mistake -- what would be the outcome?

Here the character is 59-year-old family court justice Fiona Maye, a brilliant jurist at the pinnacle of her career, handing down nuanced judgments in cases of great complexity, including a celebrated one involving separating Siamese twins. We meet Fiona on a bad day, a day that has driven her not only to drink (very rare for her) but to curse loudly at her husband, Jack (she has not used profanity out loud since she was a teenager). Jack has just announced that, due to her total loss of interest in the physical side of their relationship, he is going to have an affair. After a short, dispiriting argument, off he goes, dragging his roller bag to the car as she watches out the window.

As a woman in "the infancy of old age, just learning to crawl" Fiona is uncertain whether to fight or give in, try to save the life they had or explore what it would be like to be on her own. To avoid dealing with this confusion, she drowns herself in her work, which she's been doing for years anyway.

The book's title refers to the part of British law that governs family cases, decreeing that "the child's welfare shall be the paramount consideration." Certainly we need laws to enforce this, because, as Fiona well knows, the children are often "counters in a game, bargaining chips for use by mothers, objects of financial or emotional neglect by fathers; the pretext for real or fantasized or cynically invented charges of abuse, usually by mothers, sometimes by fathers; dazed children shuttling weekly between households in coparenting agreements, mislaid coats or pencil cases shrilly broadcast by one solicitor to another; children doomed to see their fathers once or twice a month, or never, as the most purposeful men vanished into the smithy of a hot new marriage to forge new offspring."

Fiona herself is childless, but the understanding she brings to her work is informed not only by jurisprudence but by emotional intelligence. Both faculties are challenged by the case at the center of this novel. Court is called urgently into session in the matter of a 17-year-old boy named Adam Henry, suffering from leukemia. Adam and his parents are devout Jehovah's Witnesses. Though their faith has permitted some treatment of his disease, his blood counts are now so low that he will die without a transfusion, specifically prohibited by the tenets of the church. Both the parents and the son are willing to accept the consequences, but the hospital sues to save his life.

Finding the statements made by the parents and doctors in court insufficient, Fiona leaves the bench and goes to the hospital. There she encounters a beautiful, outgoing, brilliant boy who reads her his poetry and plays violin, moving her so much that she sings a ballad along with him, a poem by Yeats set to a sad Irish tune by Benjamin Britten. But despite their connection and the arguments she puts forward, Adam Henry is firm in his decision to die.

Now it is up to Fiona, and Fiona is used to that. But though she begins on familiar footing based in law and instinct, she ends up on uncharacteristically shaky ground. Not just with the case, but also at home, when her husband turns up on the doorstep and she's not sure she wants him back.

Like "On Chesil Beach," this book is just a bit longer than a novella, a form that McEwan recently defended in The New Yorker as the acme of prose fiction. "The demands of economy," he proposes, "push writers to polish their sentences to precision and clarity, to bring off their effects with unusual intensity, to remain focused on the point of their creation and drive it forward with functional single-mindedness, and to end it with a mind to its unity. They don't ramble or preach, they spare us their quintuple subplots and swollen midsections."

That is an excellent description of "The Children Act."