Let’s not mince words: The goal here is that after reading this story, you throw down this magazine (or your preferred device), grab the keys and race to Aquebogue — yes, Aquebogue — for a plate of mashed turnips. Or to Port Jefferson for an oh-wow entrée called lobster Malabar. As tall orders go, it’s no plate of mashed turnips, but is it worth a trip? Yes! How do I know this? Because of an old maxim I am just now inventing: the greater the dish, the greater the story behind it. Take it away, turnips.

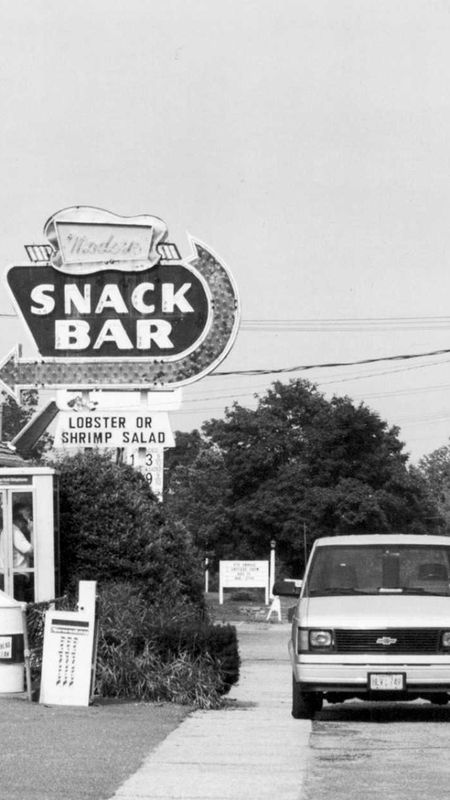

The year was 1956 when Wanda Wittmeier, along with her husband, John, took over ownership of the Modern Snack Bar in Aquebogue from Wanda’s sister Lil. For a while, the pair and their two sons, Otto and John Jr., lived in an apartment above the seasonal-only Snack Bar, which was really just that — "all short orders and six counter stools," John Jr. told me. The menu was little more than hamburgers, hot dogs and sides of baked beans until Wanda, a self-described people person, came up with a novel idea to generate repeat business: find out what customers crave and then cook it for them. "That’s how our menu developed," explained John. "That’s how we got the Long Island roast duck, the chicken croquettes, lobster salad. All of those things came from suggestions customers made way back when."

The name of the customer who first asked Wanda for mashed turnips is lost to history, but sometime around 1978, the dish made its Snack Bar debut. The elder Wittmeiers’ golden, fluffy, sweet-salty purée was an instant sensation, the recipe kept a closely guarded secret for decades, even from John and Otto (now 65 and 80, respectively). Soon the turnips began showing up on Thanksgiving tables all over the North Fork. Snowbirds refused to decamp to Florida for the winter without an Igloo-ful of frozen mashed turnips, sometimes a dozen quarts or more. People stopping by for a pint to go found themselves forking the whole thing into their mouths in the parking lot. On the Tuesday before Thanksgiving, it wasn’t unusual to see 200 people already in line for turnips when the Snack Bar opened at 11.

The mashed turnips at Modern Snack Bar in Aquebogue. Credit: Raychel Brightman

As the menu grew (I’d be remiss in not mentioning another renowned item, fried soft-shell crabs) so did the restaurant, eventually boasting 120 seats spread throughout two dining rooms. After the completion of the second of these, in 1970, expansion stopped and the restaurant, ever alert to the psyche of its patronage, began a slow transition from something-to-build to something-to-preserve, a Modern Snack Bar on the run from modernity. "It reminds old folks of a time when they were raising their families," said John, noting that four generations at one table is a common sight. "The Snack Bar has a place in their history." At times, even server Rosetta Bulak feels like a newcomer. "Some of these people have been coming here for 50 or 60 years," she said. Bulak has been there for just 35.

Once bitten by the Snack Bar bug, only death will keep someone from coming back, it seems. "A lady calls me the other day saying that her mom would like to have her last meal here," Otto told me. "Fine, I say, ‘we’ll set the table.’ " The woman, who was 97, enjoyed one final lobster salad sandwich and passed away a few weeks later.

They even come after death — or try to. Years ago, Otto fielded a call from a family whose Snack Bar–loving father was about to be buried at Aquebogue Cemetery, a stone’s throw up Route 25. "They wanted to know if they could roll him in so they could have dinner with him one last time." Wanda politely declined the request.

"The biggest compliment we get is that we’re consistent," John said. But the same principle that keeps mashed turnips always on the menu — dedication to consistency — makes removing an item nearly impossible, even briefly. From time to time, the brothers have been forced to ax their labor-intensive chicken croquettes, which the Snack Bar has served since the early ’60s. "We get really yelled at," said Otto.

"You’ve never seen people so upset about croquettes," added John. This year, when the Covid 19 crisis delayed the seasonal restaurant’s annual reopening until July (it’s normally an April-December romance) Otto and John streamlined the menu — sans sauerbraten — and braced for the pitchforks. ("We’ve definitely taken flack.") There’s zero chance they will update the curtains or take out the paneling any- time soon, despite the ’70s rec room ambience. "Who has paneling now?" John asked, shaking his head.

Still, nothing instills more fear in the hearts of patrons, or the Wittmeiers, than a turnip drought. After the one last year left them without a supply of Canadian rutabagas — technically, the dish is mashed rutabagas — the brothers were forced to canvass the globe for a purveyor in possession of enough of the root vegetable to get them through Thanksgiving. It was not easy finding 9,000 pounds of rutabagas, but a source was finally located — in Belgium. "We can’t not have turnips," noted John.

“We are not order-takers. We are inviting you into our home.”

John Wittmeier

As befitted their creed, the elder Wittmeiers maintained a consistent presence at the Snack Bar even after officially retiring in 1988. ("Retirement was just a word.") Not long before her death in 2014, Wanda could still be found sitting in the same chair at the same corner table. There, she rolled napkins around flatware and kept a close eye on the dining room, regularly intervening when things weren’t done to her specifications. "You could tell something was on her mind when the silverware was wrapped really tight," laughed John. "It took a while to undo." At some point, a portrait of Wanda rolling flatware was mounted on the wall above her favorite chair. It hangs there to this day. "Mom is watching," said Otto. "She’s always around," added John.

Indeed, no one ever seems to leave the Modern Snack Bar for good, which is exactly the point. Same people, same turnips. "People come to our restaurant because they see familiar faces," John said. "We are not order-takers. We are inviting you into our home."

Kulwant Wadhwa was born in Afghanistan two years before the Wittmeiers took over the Snack Bar. In 1994, after the country fell under Taliban rule, Wadhwa, a Sikh, fled with his wife and four daughters first to India and then the United States, settling in Port Jefferson. Although a pharmacist by training, he soon found himself running a restaurant with his brother, and, in 1996, took over The Curry Club in East Setauket, turning it into a preeminent spot. It was and remains a very traditional North Indian place, but still: Wadhwa’s journey to South Indian cuisine and lobster Malabar began there.

The road would be long and winding and full of heartache. On an October morning in 2000, Wadhwa’s wife Amargeet was out walking the family dog when she suffered a massive stroke. The brain hemorrhage left her blind and confused, and in her disoriented state, Amargeet somehow stumbled onto the tracks at Port Jefferson Station. She was hit by an LIRR train and nearly killed, losing both arms and a leg.

The same morning, 11-year-old Kiran, the Wadhwas’ youngest daughter, was on her way to school, her bus caught in a traffic snarl that, unknown to her, had been caused by the emergency response to her mother’s accident. At the time, an elder sister, Indu Kaur, was living in Virginia, another sister was in Toronto and a third having just graduated from high school, was preparing to leave for college in Boston. Knowing their mother would require round- the-clock care for years to come, the three decided to return home to help their father run the restaurant, tend to Amargeet and raise their little sister.

Sisters (left to right) Sonia Mohan, Indu Kaur, Kiran Wadhwa and Manpreet Singh on August 10, 2017 at The Meadow Club in Port Jefferson Station. Credit: Courtesy Wadhwa Family

Up until then, none of the four daughters had ever considered a restaurant career. As business at The Curry Club grew more and more over the next decade, however, it became obvious that the Wadhwas’ daughters had a gift for hospitality. In 2013, Kulwant saw an opportunity to showcase their talents. "He got the whole family together," Kiran remembered, "and we all went and saw the Meadow Club," a 17,000-square-foot, multiroom banquet hall on a busy stretch of Route 112 in Port Jefferson Station. "It was kind of like a light bulb hit us … We all just immediately loved it, and it was kind of the beginning of a career for me and my sister."

Within a year, the Wadhwas had turned the Meadow Club into one of the Island’s premier wedding and events venues. "We did, like, 22 parties on a weekend. One weekend. Did we sleep?" laughed Indu. "We did that constantly for four years." In short order, the Meadow Club became highly profitable, hosting hundreds of weddings a year, along with umpteen bar mitzvahs, baby showers, and sweet 16s. "I remember seeing the number and us being so extremely proud that we were able to expand the business so quickly," Kiran said.

In 2018, however, the Wadhwas’ lives and fortunes changed overnight yet again. One Friday evening in July, the Meadow Club hosted a 30-person wedding reception, a relatively easy lift. Normally, Indu was the last person in the building, "But that day I said, ‘It’s a very small party, my staff can handle it,’ " so she left just after midnight. At around 1:30 Indu received a call that the club was on fire. "I just picked up my slippers and went to Dad’s room, grabbed his glasses, grabbed his turban. I said, ‘Dad, let’s go.’ He said, ‘Where are we going?’ I said, ‘Don’t ask questions. Let’s just go.’ " By the time they reached the club, it was engulfed in flames. "We were on our knees and watching our building burn down."

The family was devastated, and so were the bride and groom of a 300-person wedding that was scheduled for the following night. And what of the engagement party, baby shower and christening the club had been scheduled to host the same weekend? Once again, as with Amargeet’s accident, grieving became a luxury the Wadhwas couldn’t afford. They sprang into action instead.

"They thought we would not be able to pull it all together," said Indu of the nervous couple whose wedding had been scheduled for Saturday night. "Just trust me," she told the bride. The Wadhwas frantically contacted every event space they could, eventually finding an alternate venue for every single one of them, including the wedding. The couple was both astounded and moved by the Wadhwas’ devotion, Indu recalled. "The bride said, ‘You guys just had a fire and you’re worried about me?’ I said, ‘Absolutely, it’s one day in a lifetime.’ " The couple has continued to keep in touch, sending Indu flowers more than once.

Even as the family economized, borrowing money to rebuild the Meadow Club (it’s scheduled to open in December), they sought out a space to stage events in the meantime, which led them to the Harbor Grill in Port Jefferson. The imposing seafood house, which the Wadhwas eventually purchased earlier this year, has multiple dining rooms, not to mention a large rooftop deck with dramatic views of the harbor. Indu and Kiran had long wanted to open another restaurant but didn’t want to compete with their own Curry Club.

"We wanted to bring some excitement to Indian cuisine," Kiran said. "It can be so generic. People only know North Indian cuisine. They don’t know there’s Gujarati, there’s Goa, there’s Kerala." It’s the latter state, in the far southwest of India, that has given the world lobster Malabar.

Kiran Wadhwa and Indu Kaur at SaGhar in Port Jefferson. Credit: Raychel Brightman

The sisters named their new place SaGhar ("home of the sea" in Hindi) and created a superb pan-Indian menu with Jimmy Singh, The Curry Club’s longtime chef. The restaurant generated much buzz when it opened in February, but the pandemic lockdown forced its closure just a few weeks later. On June 10, when SaGhar reopened, there was a three-hour wait for tables.

Its all-India approach includes everything from Kashmiri lamb shanks to Rasam Podi — Chilean sea bass with curry-saffron mashed potatoes and a sauce redolent of cumin, coriander and turmeric. Goan influences inform the calamari bhajiya, squid battered in chickpea flour and served with mint-tamarind chutney. From Kerala comes salmon bathed in a golden coconut curry brightened by mustard seeds — and yes, lobster Malabar, featuring crab meat along with the headliner and a velvety, golden sauce that includes citrusy curry leaves, tamarind, with its sweet- sour acidity, and coconut milk.

As for the flavor, well, it’s like something you’ve never had before and something you’ve eaten all your life. Which, come to think of it, is an equally apt description of the Modern Snack Bar’s turnips. The two dishes are nothing alike and possess no ingredients in common. With each successive bite, however, both become ever more surprising, compelling and complex on the tongue — wonderfully fulfilling the promise of their origin stories.

I’ll grab the keys.

Restaurant Information

MODERN SNACK BAR: 628 Main Rd. (Rte. 25), Aquebogue; 631-722-3655, modernsnackbar.com

SAGHAR: 111 W. Broadway, Port Jefferson; 631-473-8300, sagharportjeff.com