Newsday analysis: Suffolk police stopped, searched minority drivers at higher rates

The Suffolk County Police Department subjected Black and Hispanic drivers to tougher enforcement actions than white motorists over the past two years, stopping and then searching the minority drivers and their vehicles at higher rates than experienced by whites, a Newsday analysis of police data has found.

Officers pulled over Black drivers almost four times more often than white drivers, and Hispanic drivers twice as often, when matched against the size of the driving age population of each group in the area patrolled by the Suffolk Police Department.

More tellingly, after stopping drivers, police searched Blacks over three times more frequently than whites, and Hispanics 1.7 times more frequently, Newsday’s analysis revealed.

At the same time, Suffolk police found contraband, such as an illegal weapon or drugs, when searching Black and Hispanic drivers less frequently than when they searched white motorists.

Traffic stops for offenses such as speeding, failure to signal and broken taillights are the most common — and familiar — enforcement actions taken by police. Because officers have discretion to choose which drivers to pull over and, critically, which to search, stops can also reveal evidence of whether a department applies the laws equally to members of different races or ethnicities.

"It’s where the story begins and where our attitudes begin in terms of how we perceive law enforcement," said Jeffrey Butts, a research professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. "If you’re pulled over all the time, and you think other people are behaving the same way you are, but they’re pulling you over, you immediately start thinking that police are biased, which means government is biased, which causes you to doubt the whole enterprise of democracy and government. So, it’s really serious."

In 2014, the Suffolk County Police Department committed to collect information on driver stops and searches in an agreement stemming from a U.S. Department of Justice investigation into whether the county had failed to equitably police the Hispanic community.

While requiring Suffolk to adopt additional measures, ranging from improved hate crime investigations to anti-bias training for officers, the federal department’s Civil Rights Division highlighted statistics that counted the race or ethnicity of drivers as offering the potential for discovering whether the police force fairly enforced the rules of the road.

"Without this data, SCPD is unable to meaningfully assess whether there are disparities in search practices that suggest those practices are influenced by unlawful bias," the Civil Rights Division explained in a 2016 report.

"Further, collection of such data is not only necessary to ensure bias-free policing; such data also serves as an effective management tool and has the potential to promote efficiency by showing which law enforcement strategies are most effective."

Suffolk police made more than 230,000 traffic stops over the past two years. Newsday analyzed statistics produced by those stops — from the third quarter of 2018 through the second quarter of 2020 — and tracked trends showing how often police searched vehicles from 2016. Newsday downloaded the raw data about stops from the department’s website.

Newsday also compared the information to two of the largest databases of traffic stops in America, one compiled by the Stanford Open Policing Project at Stanford University, the other by Frank Baumgartner, a University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill political science professor and co-author of a 2018 book, "Suspect Citizens: What 20 Million Traffic Stops Tell Us About Policing and Race."

Based on this never-publicized Suffolk Police Department race and ethnicity data, the analysis found:

- The gap between how often officers searched white and Black vehicles widened over the past four years. In 2016, officers searched cars driven by Blacks at twice the rate that they searched cars driven by whites. In 2019, officers searched cars driven by Blacks 3.4 times more frequently than cars driven by whites.

- An imbalance also widened between how frequently Suffolk police searched the cars of Hispanic drivers compared with those of white drivers. In 2016, cops searched cars driven by Hispanics 1.4 times more often than cars driven by whites — a figure that climbed to 1.7 times more frequently in 2019.

- The difference between how frequently Suffolk police searched Black and white drivers is among the largest found in the data kept by the Open Policing Project and Baumgartner. It was wider than found in more than 84% of the 160 forces studied by Baumgartner. The disparity between the Suffolk PD’s search rates of Hispanic and white drivers was smaller than found in most police departments reviewed by the two studies.

- The department’s data shows that officers identified drivers as Asian in 2% of the stops and stopped or searched those drivers at lower rates than they searched Black, Hispanic and white drivers. Officers pulled Asians over 14% less often than whites on a per capita basis and searched them or their vehicles 50% less often than they subjected whites to searches.

"There are racial inequalities in stops, particularly between Blacks and whites, and also between Hispanics and whites," said Deborah Little, a member of United for Justice in Policing Long Island, an advocacy organization that is completing its own analysis of Suffolk’s data.

Formed in 2017 by Long Island Jobs with Justice and New York Civil Liberties Union Suffolk County, United for Justice also found widening disparities despite efforts to improve Suffolk police training, Little said, adding that "the results are in some major way caused by racially disparate policing practices."

Ani Halasz, executive director of Long Island Jobs with Justice, said that Suffolk’s data shows "a clear indication communities of color are being targeted in different ways, and aggressive ways, and reveals inequities in how communities are policed on Long Island."

Marcelo Lucero, who was killed in 2008. Credit: Courtesy of the Lucero Family

THE KILLING of Ecuadorian immigrant Marcelo Lucero in an attack by seven teenagers in 2008 sparked the Justice Department’s investigation of the Suffolk PD.

In shifting groups, the teens had attacked at least 12 other Hispanics in the weeks before the killing of Lucero in Patchogue. Although three men had reported being attacked, police took little action. Additional Hispanic men came forward with accounts that police had discouraged them from reporting crimes or failed to respond to complaints.

Federal law empowers the U.S. attorney general to conduct investigations of a "pattern or practice of conduct by law enforcement officers" that violates civil rights. After a five-year inquiry, the settlement agreement between the county and the Justice Department included a provision that the police department would identify the race or ethnicity of drivers who were pulled over and searched on the roads.

The police also committed to file annual reports analyzing the data, "explaining what measures, if any, SCPD will take as a result of the analysis."

For the next four years, the Civil Rights Division chronicled police department failures to collect the promised information. Those included a reported software botch in 2015 data that had indicated disparate enforcement against Black and Hispanic drivers and the introduction of an unwieldy data system that the department scrapped on its launch day in 2017.

Finally, in 2018, police officials started gathering the full range of data promised to the federal government — "all factors relevant to ensuring bias-free policing practices," according to the Justice Department’s yearly report.

"That is a considerable achievement," the agency wrote, adding, "The Department has committed to the fact that, once a year’s worth of data is collected, it will begin the analysis process and make its analysis available to the public."

Even so, the Suffolk department has yet to publicly analyze traffic stops by race or ethnicity. Instead, it published two reports that detailed other aspects of traffic stops, including the total number of stops made by officers, the count of stops made by each precinct, and the numbers of tickets and arrests that followed.

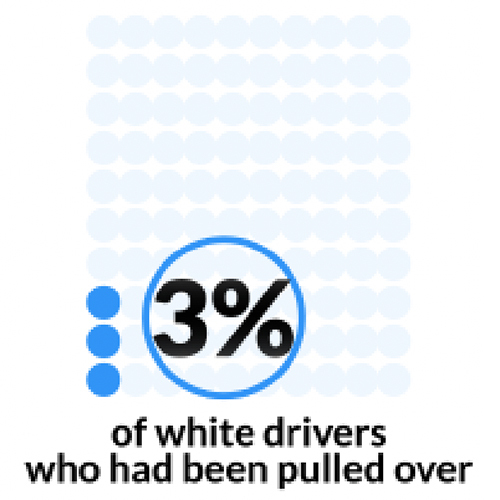

Covering two time periods — from March 2018 through December 2018 and then all of 2019 — the reports disclosed that officers executed roughly half the stops after observing speeding, stop sign violations and equipment infractions, such as broken taillights. The 2019 document also pointed out that officers searched vehicles in "only a small fraction" of stops, less than 3% of them.

Although the department’s data included the race or ethnicity of drivers, the reports did not reveal how the stops played out among members of different groups. Some community leaders have noted the omissions.

"How is it possible you can say you have bias-free policing if there’s no analysis of traffic stops by race?" said Tracey Edwards, Long Island Regional Director of the NAACP New York State. "The only way to make systemic changes is if it’s grounded in factual data that shows what policies and procedures need to change."

Edwards said she raised the lack of racial analysis last year in a meeting with Suffolk Police Commissioner Geraldine Hart.

In an interview this summer about police reforms, Hart said the department had retained the Albany-based John F. Finn Institute for Public Safety to analyze the data for racial disparities.

"We're going to make sure that we are utilizing that information to hold our officers accountable so that if we're seeing a disproportionate rate of people being stopped in communities of color we are absolutely going to make sure that we are instructing our precinct commanders to review that data and hold their officers accountable," she said.

Newsday on Monday emailed its key findings to Hart and police department press aides and requested comment. There was no response by deadline.

Newsday requested similar traffic stop data from the Nassau County Police Department. The department, which is not under a federal agreement to collect the data, declined to provide a full accounting of the information it maintains or to make it public.

A Suffolk County police officer's dashboard computer from 2016. Credit: Chris Ware

SUFFOLK POLICE USE in-car computers to collect traffic stop data.

After pulling over a vehicle, an officer is required to hit a button that says "T-STOP" and enter information, including the time and location of the stop. When the stop is over, the officer enters the gender, age and apparent race and ethnicity of the driver. The officer must also report whether he or she asked the driver to get out of the vehicle, whether the officer searched the driver or vehicle and whether the search turned up contraband.

Additionally, police department regulations direct officers to cite their reasons for pulling over drivers and the legal authority for conducting searches. Barring "unreasonable searches and seizures," the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution governs when police may pull over a car and then, for example, open its trunk or pat down its driver.

To gauge how police interacted with members of different racial and ethnic groups on the road, Newsday analyzed the raw data found on the SCPD website by whether drivers were white, Black or Hispanic. In the process, Newsday eliminated 506 stops because they appeared in the data more than once, were incomplete or occurred outside the police district.

At each level of enforcement — from ordering drivers to pull over, to commanding drivers to exit their vehicles, to subjecting drivers to searches — Newsday’s analysis of the department’s data showed that officers focused on minority drivers, particularly Blacks, more than white drivers.

Jonathan Smith supervised the Justice Department’s investigation of the Suffolk police while serving as the chief of the agency’s Special Litigation Section, a post he has since left. Told of Newsday’s analysis, Smith responded:

"When you see all the disparities compound, that indicates race is playing a factor, from the stop to all the ways officers interact with motorists."

PULL TO THE SIDE OF THE ROAD, PLEASE

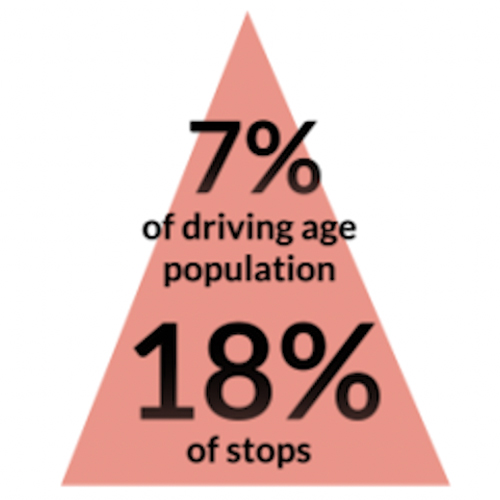

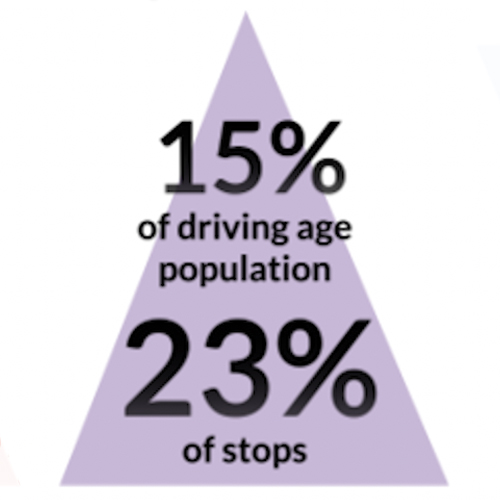

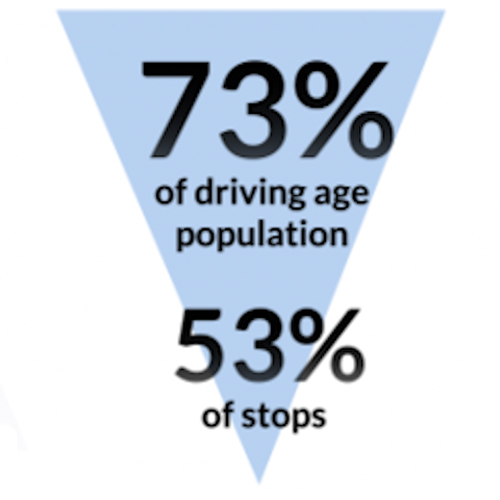

Who was stopped:

Police stopped Black and Hispanic drivers more compared with whites.

Black

Hispanic

White

Rate of stops per capita:

TRAFFIC STOPS ARE the most common interactions most people have with law enforcement. Because stops interfere with individual liberty, police need proper legal grounds to conduct them.

When an officer witnesses an offense, such as running a red light, the officer is deemed to have probable cause to stop a driver. Alternatively, an officer may act on reasonable suspicion. The U.S. Supreme Court has defined reasonable suspicion as a clear and articulable reason for believing that a crime has occurred or is about to occur. For example, an officer who sees someone walk unsteadily out of a bar and drive away may have grounds to stop the driver on reasonable suspicion of drunken driving.

To analyze racial or ethnic patterns in traffic stops, researchers start by comparing how frequently police pulled over members of different groups with their presence in the population. By this measure, if Blacks, Hispanics and whites each make up one-third of the population and account for one-third of drivers pulled over, stops would be in perfect balance.

Newsday followed this method, matching the frequency of stops in the Suffolk PD’s data against driving age populations in the territory patrolled by the force, as counted by the U.S. Census. The calculations have limitations. They do not account for drivers of all races and ethnicities who happened to pass through the patrol area, nor do they account for possible variations in driving rates among Blacks, Hispanics and whites.

Still, the comparisons are commonly used by researchers as an element to measure the fairness of traffic enforcement — when combined with additional, firmer yardsticks.

"This is always a place to start the analysis," said Cheryl Phillips, co-founder of the Stanford Open Policing Project.

Suffolk’s data showed that police stopped Black and Hispanic drivers at rates that were larger than their proportions of the driving age population.

Recording how many times officers stopped Black, Hispanic and white drivers — Blacks, 41,727 times, Hispanics, 53,353 times, whites, 121,753 times — the data also provided a basis for calculating how frequently police pulled over members of each group on a per capita basis.

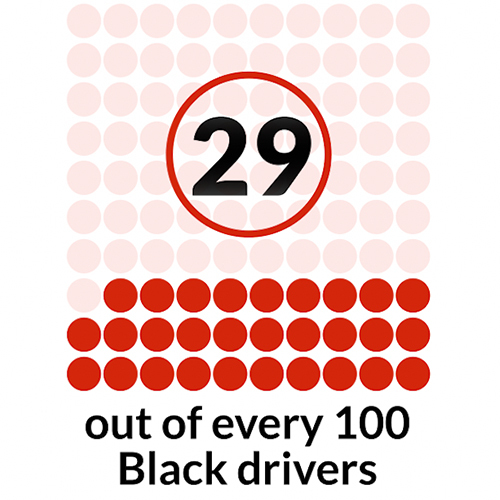

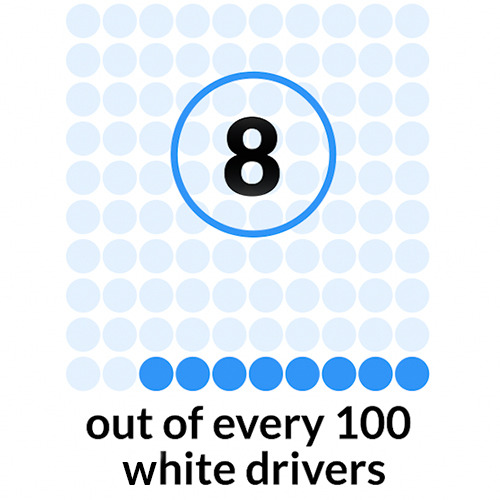

For Blacks, the figure was 29 out of every 100 people of driving age per year, or almost three in 10. The corresponding numbers for Hispanics was 17 of every 100 driving age population, or about one in six, and eight of 100 white driving age population, or fewer than one in 10.

By those per capita measures, Suffolk police pulled over Black drivers 3.7 times more frequently than white drivers and Hispanic drivers 2.2 times more often than whites — disparities that Baumgartner described as both "remarkable" and "huge." In comparison, he noted that in North Carolina, where a state law requires every police department to collect traffic stop data, officers have pulled over Blacks 1.6 times more frequently than whites.

An Open Policing Project review of stops by 35 municipal police forces, which did not include Suffolk County, found a wide range of per capita disparities.

Suffolk’s per capita rates of stopping minority drivers was higher than the average per capita rate among those departments, while the rate for white drivers was lower: 45% higher for Blacks, 89% higher for Hispanics and 43% lower for whites. Stanford researchers published their average rates in a May 2020 paper in Nature Human Behavior.

Little, with United for Justice in Policing, highlighted the evidence that police had stopped almost three in 10 Black drivers.

"It’s a huge number and a huge difference" compared to white drivers, she said. "It validates the reality of what people are feeling and experiencing. These are real differences happening to you, your family and friends."

Suffolk’s data also indicated that officers tended to stop whites and Blacks for different reasons, pulling over Black drivers 21% less often than whites for speeding and other moving violations but 62% more often for equipment violations. Similar disparities have emerged in numerous studies of traffic stops.

STEP OUT OF THE VEHICLE, PLEASE

Police ordered Black and Hispanic drivers to exit vehicles more compared with whites.

THE U.S. SUPREME COURT has granted police broad power to order drivers out of their cars after legally pulling them over.

In a 1977 ruling, the court weighed safety considerations during a traffic stop against a driver’s right to be left alone. Citing the dangers officers can face after stopping drivers who are armed, as well as the dangers posed by passing vehicles, the court wrote that the "intrusion into (the driver’s) personal liberty" at being ordered out of a car was "at most, a mere inconvenience" while police needed the power to take potentially life-preserving precautions.

"Establishing a face-to-face confrontation diminishes the possibility, otherwise substantial, that the driver can make unobserved movements; this, in turn, reduces the likelihood that the officer will be the victim of an assault," the court wrote.

As a result, officers have authority to decide which drivers to order out of their vehicles.

"They can order a driver out of the car with some evidence or no evidence whatsoever," said David Harris, a University of Pittsburgh Law School professor who specializes in "police behavior, law enforcement and race" according to his professional profile.

Traffic stop researchers focus closely on police officers’ actions after they have pulled over drivers, including whether the officers order drivers to leave their cars and whether they search the drivers. In those cases, they compare how officers treated members of different groups as part of the overall number of people who had been stopped.

"Once the drivers have all been stopped, we know what the baseline population is, it's all drivers stopped," said Harris. This allows researchers to compare how police interacted with members of racial and ethnic groups in a fixed universe of people.

Neither the Open Policing Project nor Baumgartner track how frequently police order drivers out of their cars because most police forces do not publish data about exit-the-vehicle orders. Thus, it was not possible to gauge the Suffolk PD data on this aspect of the department’s traffic stops against the performance of other departments.

But the data generated by the Suffolk’s 230,756 stops enabled Newsday to determine that officers reported ordering drivers from their cars 9,621 times and to calculate that they reported giving the command to Black drivers 2.7 times more frequently than to white drivers, and to Hispanic drivers 1.6 times more often than to white drivers.

OPEN YOUR TRUNK, PLEASE

Police searched Black and Hispanic drivers or their vehicles more compared with whites.

THE LAW SPELLS OUT when a police officer may search a driver or vehicle without a warrant during a traffic stop — with different rules applying under different conditions. Here are four types of searches tracked in the Suffolk PD’s data:

- An officer may pat down a driver using a "protective frisk" when the officer has reason to believe that the driver is armed.

- When an officer spots evidence of contraband — for example, drugs or a weapon — through a car’s windows, the officer has probable cause to conduct a "plain view" search of the vehicle.

- An officer has probable cause to search a driver or vehicle when the officer detects other evidence of a crime, such as an odor indicating that a driver had been smoking marijuana at the wheel.

- A driver gives an officer permission to conduct a "consent search" even though the officer has no other legal authority to search the driver or the vehicle.

In each category, the data showed that Suffolk police searched minority drivers and their vehicles more often than white drivers and their vehicles — overall subjecting Black motorists to searches 3.5 times more frequently than whites, and Hispanics 1.7 times more frequently than whites.

The department’s database extends back to 2016 in recording the number of times that officers searched vehicles rather than drivers. Since then, the data shows a widening gap between how frequently officers searched the vehicles of white and minority drivers. The difference for Blacks started at 2.1 times more often four years ago and rose to 3.4 times more often last year, and grew for Hispanics from 1.4 times more often to 1.7 times more often.

Informed that Suffolk’s database indicates that officers searched minorities more frequently than whites, Butts of John Jay College said, "That would tell me if you're white, you have to look pretty sketchy for them to think they're going to want to search you."

Harris, the University of Pittsburgh law professor, said that disparities in how often police search members of different groups during traffic stops give "a very good idea of how police are using their discretion."

Calling Newsday’s analysis of the Suffolk police data "very concerning," he added:

"What's probably behind that, as it is in all these other studies, is that in fact, Blacks are considered more suspicious in their behavior than whites," Harris said. "That is why more of them get searched with less success than with whites."

Harris and other researchers use the term "success" to describe searches in which police have discovered contraband such as drugs or weapons.

In the 1950s, Nobel Prize-winning economist Gary Becker proposed that comparing success rates achieved by police when searching members of different groups could provide evidence that officers had used varying standards in selecting the people they had searched.

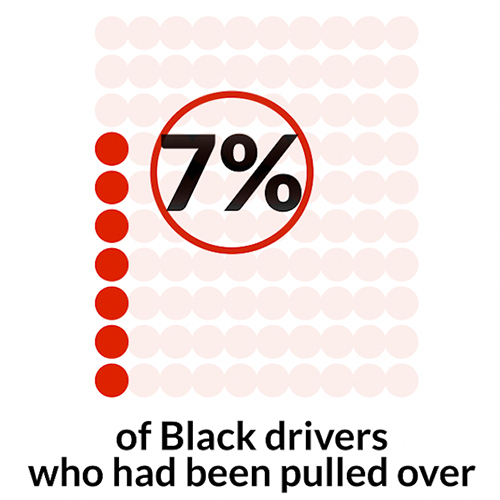

Under this so-called outcome test, officers would find contraband at roughly the same rates when searching white and minority drivers if the officers used the same standards at all traffic stops. Conversely, if officers found contraband less frequently when searching minorities than when searching whites, the outcome test suggests that the officers more readily suspected minorities than whites of criminality — producing a greater rate of searches that turned up nothing.

"When Blacks are searched at higher rates but are less likely to be found with contraband, the disparity is taken as unjustified targeting of Black drivers," Baumgartner wrote in his book on traffic stops.

The U.S. Justice Department had adopted the outcome test as a means to detect evidence of biased policing.

The report of its investigation of the Ferguson (Missouri) Police Department after the 2014 fatal shooting of Michael Brown included findings that officers had discovered contraband less frequently when searching Blacks than when searching whites during traffic stops.

The report stated that "the lower rate at which officers find contraband when searching African Americans indicates either that officers’ suspicion of criminal wrongdoing is less likely to be accurate when interacting with African Americans or that officers are more likely to search African Americans without any suspicion of criminal wrongdoing."

"Either explanation suggests bias, whether explicit or implicit," the report concluded.

Following standards used by Stanford and Baumgartner, Newsday focused on encounters when police asserted they had legal grounds to make searches based on suspicion or after they obtained permission for a search. That excluded searches police were required to conduct after making an arrest.

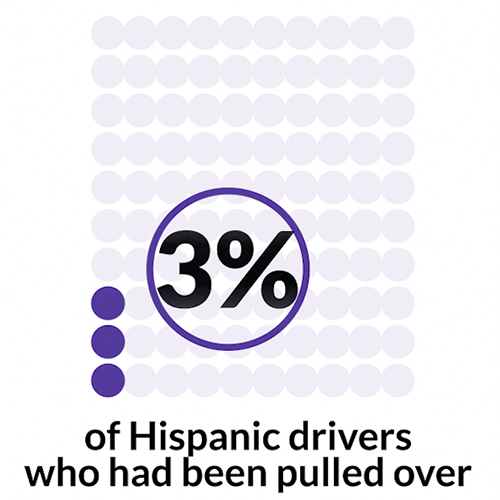

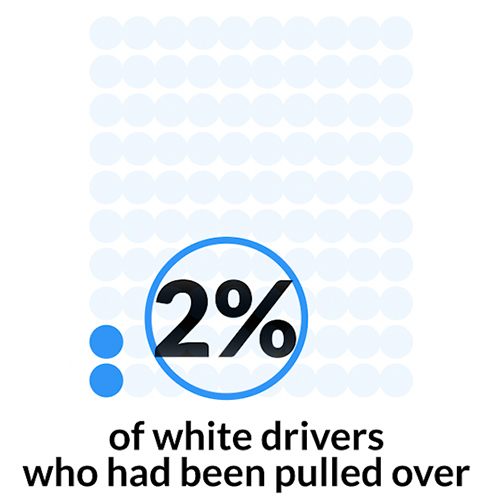

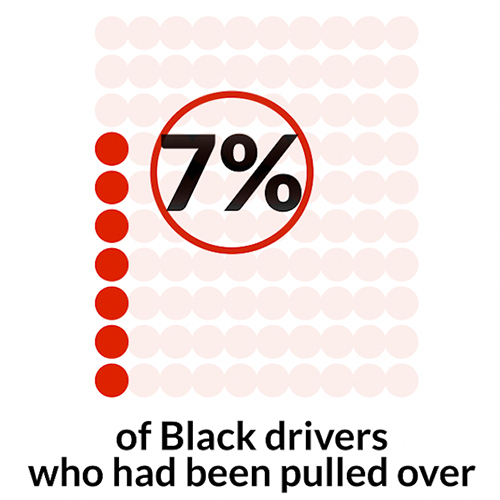

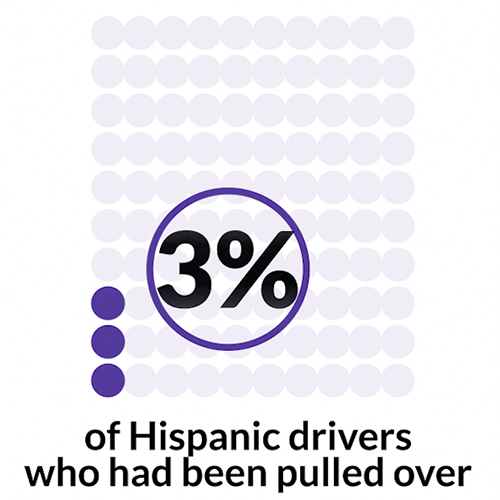

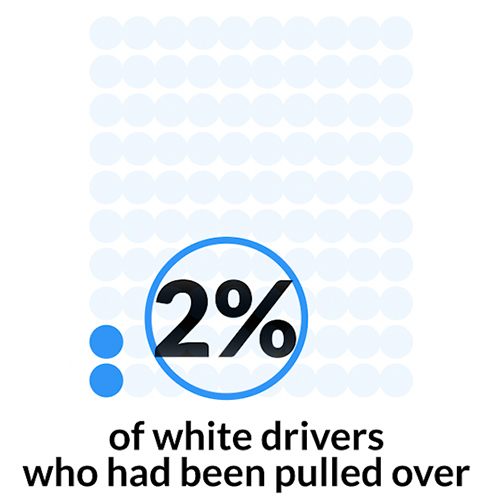

The analysis showed that Suffolk officers found contraband 56% of the time when searching whites, 51% of the time when searching Hispanics and 50% of the time when searching Blacks. Those figures translate to officers finding contraband on Hispanics and Blacks 10% less often than on whites.

The disparities were still larger in the 1,086 stops with consent searches, where officers asked permission to conduct searches in instances where they didn’t have the legal authority to order one. There, officers reported finding contraband 18% of the time while searching Blacks and 17% of the time while searching Hispanics compared to 24% of the time with white drivers. The Black searches found contraband 23% less frequently than the white searches and the Hispanic searches found contraband 30% less frequently.

Looking at all searches, including those excluded because they happened after an arrest, the statistics indicated that the department found contraband at roughly equal rates in searching Blacks and whites — 48% of the time for whites and 47% for Blacks. The difference was larger in searches of Hispanics — 48% for whites compared with 44% for Hispanics.

"If you have a disparity in searches, and you're finding contraband less often on the minorities, that's an indication of discrimination. That's not an indication of good police work," said Phillips, of the Open Policing Project. She also said:

"Suffolk County, like almost every jurisdiction we've looked at, has a problem with the way it treats minority drivers. That’s evidence of discrimination."

This story was edited by Arthur Browne and Keith Herbert.

'Success is zero deaths on the roadway' Newsday reporters spent this year examining the risks on Long Island's roads, where traffic crashes over a decade killed more than 2,100 people and seriously injured more than 16,000. This documentary is a result of that newsroom-wide effort.