The Suffolk County Police Department has opened an Internal Affairs investigation into alleged misconduct in a promotional process designed to advance sergeants to detective sergeants, Newsday has learned.

Commissioner Geraldine Hart confirmed the investigation in response to Newsday’s questions about apparently selective distribution of information that could help a sergeant correctly answer questions during an interview with the department’s brass.

"An allegation of misconduct during a recent promotional process for detective sergeant was brought to my attention last month," Hart wrote in an emailed statement. "I immediately made an administrative referral to the Internal Affairs Bureau, and an investigation was initiated, and the promotional process halted."

Hart’s action put on hold plans to award detective-level promotions under newly established procedures that had been approved by the U.S. Justice Department, which oversees Suffolk police personnel practices under a decades-old consent decree.

Establishing a fair promotions process is one of the final hurdles the county must meet to win release from federal oversight, Hart told Newsday last year. She is due to leave the department May 7 to become Hofstra University’s public safety director.

Promotions to ranks including sergeant, lieutenant and captain are governed by how well candidates score on Civil Service tests. In contrast, state law gives the police commissioner power to select police officers for promotion to detective, and sergeants for promotion to detective sergeants.

The jobs are coveted because officers are relieved of patrol duties, wear plainclothes and are responsible for investigating crimes or supervising investigations. Securing a promotion can entail a pay raise along with the opportunity to earn overtime pay.

Suffolk Police Headquarters in Yaphank, Tuesday, Nov. 26, 2019. Credit: Newsday/Steve Pfost

The Justice Department criticized Suffolk in a March 2019 letter for "the use of personal connections" in choosing who became detectives and detective sergeants. The federal agency found that the department’s reliance on connections had the effect of blocking applications from qualified minority or female candidates.

In December that year, Hart published reform orders. They specified that a panel of high-ranking officers assigned to the chief of detective’s office would interview each promotion candidate about "relevant laws and procedures," and rate how the candidate performed.

The interview topics cover issues such as when police may legally conduct searches without warrants, when suspects have the right to a lawyer, and how to handle a witness who comes forward after a suspect has been arrested.

As ordered by Hart, the interview panel’s supervisor, identified in the memo only as a ranking member of Chief of Detectives Gerard Gigante’s staff, kept a list of the topics, along with sample questions and answers that the panel could use to evaluate whether candidates answered questions correctly.

Suffolk County Police Commissioner Geraldine Hart inside her office at Suffolk Police Headquarters in Yaphank, Tuesday, Nov. 26, 2019. Credit: Newsday/Steve Pfost

The order required the panel supervisor to discuss "the questions and expected responses" with a deputy chief before an interview. It also directed the panel supervisor to "meet with the panel members in advance of the interviews and assign and discuss topics and sample questions with them so the they may re-familiarize themselves."

A sergeant who was seeking promotion to detective sergeant received five typewritten pages of the prepared questions and answers before meeting with the interview panel. Multiple ranking department sources identified the sergeant as Robert Strecker, assigned to the property section.

The sources declined to be identified, citing the Internal Affairs investigation.

Strecker notified the department brass that he had received the material only after he had met with the interview panel, the sources said.

Strecker declined to comment.

The investigation is seeking to trace the document’s path from the chief of detectives’ office to Strecker.

In addition to describing the interview process, Hart’s memo also directed superior officers to contact candidates who were given low grades, encourage them to reapply in a year and be ready to explain how the candidates had fallen short.

"These candidates, if they desire, shall be given feedback on the interview," the memo stated. "Areas in need of improvement will be discussed. This interaction shall be documented in the applicant's file."

Two sources said that, following Hart’s feedback directive, the document was sent through official channels to a detective sergeant who was ordered to speak with an officer who had gotten a low rating in an interview for detective and might want to reapply. Newsday was unable to confirm how a copy then reached Strecker.

The five pages represent only a portion of the question-and-answer material used by the interview panel. Obtained by Newsday, they included questions such as:

You arrest a person for Grand Larceny. He has a pillbox in his pocket.

Q. Can you search that person without a warrant?

A. Yes

Q. How about a wallet found in his pocket?

A. Yes

Q. How about a cellphone that was found in his pocket? Can you go through its contents?

A. No.

"This administration takes the allegation very seriously; and if misconduct is revealed, we will take immediate action," Hart’s statement said. She declined Newsday’s request for an interview.

Before his interview, Strecker sought to bolster his chances of promotion through political support, according to four people with direct knowledge of his efforts.

At Strecker’s request, sources told Newsday, Suffolk Conservative Party leader Mike Torres asked county Democratic Chairman Rich Schaffer to intercede on his behalf with Chief of Detectives Gigante. Schaffer did not reach out to Gigante, two sources said.

Torres and Schaffer declined to comment, as did a Justice Department spokeswoman.

Lt. James Gruenfelder, president of the Suffolk County Superior Officers Association — the union that represents Strecker — did not return repeated messages.

While focusing on the role "connections" had played in promotions, the Justice Department’s 2019 letter stated that "non-merit-based criteria" could lead to violations of federal law prohibiting employment discrimination.

Carolyn P. Weiss, a senior trial attorney with the federal agency’s Employment Litigation Section, also cited the 2018 promotion of Salvatore Gigante to head the Suffolk District Attorney’s detective squad. Salvatore Gigante is the nephew of Chief of Detectives Gigante, who police officials said removed himself from that promotion process.

Hart testified at a legislative hearing that Salvatore Gigante was the best qualified person for the job. An outside counsel hired by the county Legislature to investigate the promotion concluded, however, that Salvatore Gigante secured the job even though he lacked the minimum qualifications for the position and more experienced candidates had applied.

Det. Sgt. Jeffrey Walker was passed over for the position. He filed a whistleblower complaint with the county Legislature’s then-Presiding Officer DuWayne Gregory, prompting the hiring of outside counsel.

Det. Sgt. Tulio Serrata also questioned why he wasn’t given the opportunity to interview for the position.

The job is considered a plum assignment because the DA’s lead detective works in plainclothes, is provided a car and can pull down thousands of dollars in overtime pay. In 2018, two detective sergeants working in that unit earned $308,502 and $336,708.

Because of Salvatore Gigante’s familial relationship to the chief of detectives, the Suffolk County Legislature considered whether to grant a waiver to the county’s nepotism law. The Legislature rejected the waiver, blocking Gigante’s promotion.

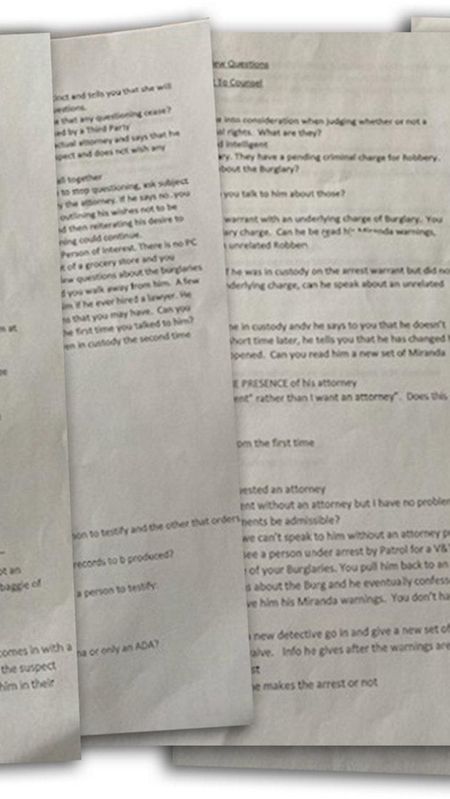

Sample Q&A material used by the interview panel obtained by Newsday

You arrest a person for Grand Larceny. He has a pillbox in his pocket.

Q. Can you search that person without a warrant?

A. Yes (incident to arrest because it was found on him)

Q. How about a wallet found in his pocket?

A. Yes (same as above)

Q. How about a cellphone that was found in his pocket? Can you go through its contents?

A. No. Not without an exception or a S/W (search warrant)

You make a car stop. You see a bag of heroin in plain sight in the center console.

Q. Can you search the entire car?

A. Yes.

Q. Can you open the glove box?

A. Yes.

Q. Can you open the trunk?

A. Yes.

Q. If you find a locked briefcase in the trunk, can you search it?

A. Yes.

Q. What if you can’t get it open, can you force it open?

A. Yes.

There are three things that the courts take into consideration when judging whether or not a person has legally waived his constitutional rights.

Q. What are they?

A. It must be knowing, voluntary and intelligent.

You have read Miranda warnings to someone who is in custody, and he says to you that he doesn’t want to speak without an attorney. A short time later, he tells you that he has changed his mind and wants to tell you exactly what happened.

Q. Can you read him a new set of Miranda Warnings and begin questioning?

A. No, not unless he is IN THE PRESENCE of his attorney.

Q. What if he said, I won’t sign the statement without an attorney, but I have no problem speaking with you. Will his oral statements be admissible?

A.No. Once he says attorney, we can’t speak to him without an attorney present.

There are two types of subpoenas: One that orders a person to testify and the other that orders records or evidence be brought before the court.

Q. What is the type of subpoena called that orders records to be produced?

A. Subpoena duces tecum.

Q. What is the type of subpoena called that orders a person to testify?

A. Subpoena ad testificandum.

Q. Who can issue a subpoena?

A. A court or any attorney.

Hochul's State of the State ... Disappearing hardware stores ... LI Volunteers: Marine rescue center ... Get the latest news and more great videos at NewsdayTV