Oluwatoyin Adewumi had a problem. As she and her son Tanitoluwa, then 10, strode through a busy Chicago airport in August, other travelers kept stopping them to ask about the shiny 4-foot-tall trophy Tani lugged to their gate. The mother and son didn't want to miss a flight on their trip back home to Long Island.

Tani had just won the under-12 division of the North American Youth Chess Championships, going undefeated by winning seven games and drawing two. The championship was another milestone in his quest to become the youngest person to reach the top title of chess grandmaster. (See sidebar.)

Tani's mom giggled recently in recalling how flight attendants helped them stow the prize — nearly as tall as Tani himself — in an overhead bin.

"Almost everyone in the plane was asking him, 'Oh my God, you play chess?'" she said.

Well, check!

Their airport episode was just a blip in the remarkable odyssey of the Adewumi family — Oluwatoyin, 40; her husband, Kayode, 45; and their sons, Austin, 18, and Tani, now 11. Over the past six years, they have gone from being targets of anti-Christian terrorists in Nigeria to homeless refugees in Manhattan to residents of their own home in Port Jefferson Station. And all of that served as a backdrop to Tani's astonishing rise to a chess master celebrated in TV, internet and print media.

The family said its troubles began back in 2015, when four men entered the print shop Kayode owned in the Nigerian capital of Abuja with an order for 25,000 posters. Kayode said he was shaken when he plugged their flash drive into his computer and found the poster said, "Kill All Christians" and "No to Western Education."

The men were from the deadly Boko Haram terror network. The Adewumis are Roman Catholic and deeply religious. When the militants returned to Kayode's office, where he displayed a crucifix on a wall, he pretended his computers were broken and gave back the flash drive.

Weeks later, two men burst into the Adewumi home and threatened Oluwatoyin at gunpoint while the boys slept. The men flipped furniture in search of Kayode's laptop. He was out at a business meeting. Oluwatoyin, raised Muslim, begged the men in Arabic to leave. Finally, they did.

Over the following months, the men returned, shouting and banging on the doors of the family home in Abuja and again 200 miles away in Akure, where the family had gone to hide.

It was too much. With tourist visas for an as-yet unscheduled trip, the Adewumis fled to America to stay with the family of one of Oluwatoyin's uncles in Dallas.

There, they marveled at the United States. Tani noticed that the power never went out. The roads were smooth. However, after about after five months, Kayode grew restless to work, and the Adewumis felt underfoot at their relatives' home.

Petition for asylum

They rode a bus to New York, where Phillip Falayi, a Nigerian immigrant and the pastor of Hosanna City of Refuge Church in Rosedale, Queens, helped the family enter a Manhattan homeless shelter. The parents stayed in a room on one floor, and Tani and Austin in a room on another. The family also petitioned the U.S. government for asylum, allowing them to stay in the country legally.

Both boys entered public schools. At PS 116, Tani saw a flyer for a chess club. He asked his mother about it.

She told club organizers that the family lived in a homeless shelter, and coach Russ Makofsky waived the $330 fee.

Back in Nigeria, Austin had once shown Tani a crude version of chess with pieces made of paper. Now, their mother bought a $5 set. Sometimes, after the family gathered for their nightly ritual of prayer and songs, the boys stayed up to play chess. Tani also did chess puzzles on his mom's cellphone.

The family slowly built a new life. Twice a week, Oluwatoyin rode buses and subways to use a kitchen at the Rosedale church to prepare Nigerian dishes for her family. Kayode took an overnight job washing dishes at a Bronx restaurant. Later, the couple teamed up to clean apartments. Then Kayode rented a car to work as an Uber driver while he studied for a real estate license. The family attended services at City of Refuge in Queens and at St. Patrick's Cathedral in Manhattan.

And Tani passionately played chess.

At chess camp in the summer of 2018, just weeks before Tani turned 8, coach Shawn Martinez experienced an epiphany about his student. He said Tani approached and said, "Coach Shawn, look what I remember."

At a chessboard, Tani played out each move of a famous game between 19th century American chess master Paul Morphy and his father.

"I remember being so impressed and so in shock," Martinez told Newsday. Tani's ability to memorize a full game indicated genuine talent.

Tani recalled that moment recently. "That’s probably one of the best games in history," he said, seemingly unimpressed with himself.

In March 2019, Tani entered the K-3 division of the New York State Scholastic Chess Championships in upstate Saratoga Springs and won five games in a row. In one game, recalling a Morphy tactic, Tani sacrificed a bishop to gain an advantage. Martinez call it "a master-level move."

In his last game, Tani blundered on one move, but before his opponent reacted, Tani extended his hand and offered a draw — neither a win nor a loss. The opponent accepted. Tani left the board disappointed, but with 5.5 points for the tournament, he had won the event. Makofsky lifted him into the air in celebration.

'It was wildfire'

Makofsky then alerted The New York Times that a boy living in a homeless shelter had won a New York State chess championship. A Sunday piece by columnist Nicholas Kristof carried the title "This 8-Year-Old Chess Champion Will Make You Smile."

"Kristof's article hit and it just, oh my goodness, it was wildfire …," recalled Makofsky, who as a boy played chess while attending Tangier Smith Elementary School in Mastic Beach. "By Sunday evening, I was being contacted by all of the major networks."

Tani appeared on TV and websites, and in newspapers, including Newsday. "Everyone gathered around something so transformative and positive," Makofsky said.

Generous donors gave the family a two-bedroom apartment rent-free for a year and a car. Makofsky set up a GoFundMe account for the family, raising $200,000 in less than a week.

In a surprise, the Adewumis said they would donate a portion to the church in Queens that helped them and set up a foundation to donate the rest of the money. "It is a blessing to us; we have to bless others," Tani's mother said.

The family said the money has gone to fill school backpacks for needy children, to a Nigerian educational organization called Chess In the Slums, and to other GoFundMe accounts of homeless people. (Donations still trickle in to the original Adewumi crowdfunding account, more than $256,000 by mid-September.)

Former President Bill Clinton invited the family to his office in Harlem. A framed poster of that visit hangs on a living room wall in the family's three-bedroom home today. "I didn’t know who he is," Tani admitted about Clinton. "I was very happy. We had a good conversation. We just talked about statues and some about chess, too."

Three books were published: a children's volume, "Tani's New Home," as well as young-reader and adult versions of "My Name Is Tani … And I Believe in Miracles," which the family wrote with author Craig Borlase. In addition, comedian Trevor Noah's Zero Day Productions acquired movie rights to their story. (No release date has been announced.)

After a year in their new apartment, the family moved to another on 24th Street. During the pandemic school year, both boys took classes online. (Along with millions of pandemic shut-ins, Tani enjoyed the chess drama "The Queen’s Gambit" on TV.)

Meantime, Tani studied chess, sometimes 10 hours a day. He did so on a computer, but also used a home chessboard to analyze strategies from his favorite book, "My 60 Memorable Games," by chess legend Bobby Fischer.

Martinez recognized that Tani needed advanced instruction, so he suggested that the Adewumis hire Giorgi Kacheishvili. The 44-year-old grandmaster now coaches Tani remotely two or more times a week from his home nation of Georgia.

Tani's hard work paid off in May, when he won a tournament in Connecticut. His victories there earned him the title of national master, making him the 28th-youngest person to do so, according to the U.S. Chess Federation.

The feat also ignited a new round of news coverage.

"I wondered: Is this kid really that good?" Kristof wrote in a follow-up column. "It turns out he is."

Search YouTube and you will find Tani in more than a dozen videos. He enthusiastically plays chess with two of his favorite grandmasters, American superstars Fabiano Caruana and Hikaru Nakamura, as well as 2019 U.S. women's champion Jennifer Yu.

Kayode Adewumi said his son "has the wisdom of an adult" and stays unaffected by fame.

"We praise God; he moves on," the father said. "He sets his new goal for himself. He doesn’t go to the internet. He plays chess."

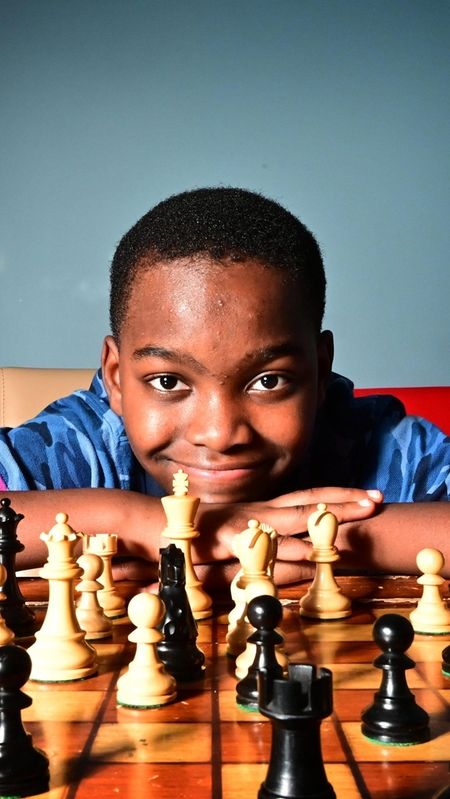

Tani Adewumi's newest chess trophy is nearly as tall as he is. Credit: Newsday/Thomas A. Ferrara

A move to Long Island

The Adewumis' path turned again in January when they moved to Port Jefferson Station. Kayode Adewumi said they bought their home with proceeds from the books and movie rights.

The father sells homes with Douglas Elliman Real Estate and is studying marketing at Nassau Community College.

Austin has enrolled at Suffolk County Community College and hopes to one day study marine engineering. Early this month, Tani entered sixth grade at John F. Kennedy Middle School in Port Jefferson Station. Two days before starting, he said he wouldn't mind if no one there knew about his chess success. "I would like it to be mysterious," he said.

After a busy summer during which Tani competed in North Carolina, Philadelphia, Albany, San Diego and Chicago, Oluwatoyin said the school year might allow her to be less of a chess mom and to find work as a patient care technician in a medical office.

At home, the family holds fast to its Nigerian roots. Kayode, who is descended from Nigerian royalty, said he teaches his sons to respect the family name. "When you are trying to protect your name, you will do the right thing every time," he said.

Each morning, in a sign of respect from Nigeria's ethnic Yoruba tradition, each son reaches to the floor, as if doing a quick pushup, and says "Good morning" to his parents.

"We tell them, 'Good morning, God bless you,'" their mother said.

In the summer, Tani devoted himself to chess morning to night, breaking for meals and to play basketball outside. Now, despite his compulsion to vanquish kings, schoolwork takes priority.

"There's no room for, 'OK, I have to play chess and leave my homework,'" Oluwatoyin said. "No. When it's time for homework, you do your homework. When it's time for chess, you do your chess."

On school nights, Tani might play online until about 10. Each night, the parents and sons kneel in the living room for prayers and Bible readings. "We sing worship songs," Oluwatoyin said. "We praise God."

During a recent visit by a reporter and a photographer, Tani's Chicago trophy stood tall in the living room — too big to join others atop his bedroom dresser.

Both parents reflected on their family's journey.

"It is the blessing of God," Kayode said.

"I never believed we could be where we are today," Oluwatoyin said. "We know God can do anything."

Race against time

In his quest to become the youngest chess grandmaster ever, Tani Adewumi’s fiercest opponent might be time.

Of millions of players worldwide, only 1,738 people are recognized as grandmasters by the International Chess Federation. The title signifies mastery of the game and is held for life. It opens doors to compete for tens of thousands of dollars. And it elevates a player to the level of greats like the late Bobby Fischer or the current No. 1-rated player, world champion Magnus Carlsen of Norway.

Fischer became the youngest grandmaster at 15 years, 6 months and a day in 1958. Since then, the record has been broken several times. In June, Abhimanyu Mishra of Englishtown, New Jersey, became the youngest grandmaster at 12 years, 4 months and 25 days.

Tani, who turned 11 on Sept. 3, earned the title of U.S. Chess Federation national master in May by winning a tournament in Connecticut, but he still has a long way to become a grandmaster at any age.

Chess rates players based on skill. Tani’s International Chess Federation rating is 2020. To become a grandmaster, he needs to reach 2500. (Carlsen’s is 2855.) Tani also must earn three “norms” by playing well in events involving grandmasters.

With in-person competition rare during the pandemic, Abhimanyu’s father took his son to Hungary earlier this year to play regularly against grandmasters. The gambit worked.

Tani will still seek high-level competition in America, but Tani’s father, Kayode Adewumi, wants to take his son abroad. He says Tani has been invited to play in Spain, Sweden and Dubai. For now, however, with their U.S. asylum applications pending, they risk not being readmitted if they leave the country.

Kayode said the family’s next immigration hearing is not until June, a long time to wait.

Carolina Curbelo, an immigration lawyer in Ridgewood, New Jersey, plans to file a petition to expedite their application. She is working with Heather Volik, a corporate lawyer in Manhattan, and Mayer Brown, a prominent international law firm, all pro bono.

Curbelo called the situation unique.

“I’ve never had a case where a client says, ‘Hey, I want to travel outside of the United States and go engage in a tournament,’” she said. “Most of my asylum-seekers are scared to even just board a plane just even domestically” for fear of jeopardizing their status.

“It’s a case where I think the American public can get behind,” Curbelo said. “Tani and his family are the example of an immigrant that we want in this country. I mean they’re individuals who have not committed a crime. They’re individuals who are hardworking. They’re God-fearing people. They give back to the community not only through their religious activity but through their charity work from chess.”

Emily Allred, a curator at the World Chess Hall of Fame in St. Louis, studied upstart players for a current exhibit, “Masterminds: Young Prodigies.”

“Just coming to the U.S. under the circumstances that they did, and establishing themselves, that’s just a remarkable story in itself,” she said of Tani’s family. “And then you’ve got him learning to play chess and rising to the top of the game. That’s like a fairy tale.”

But she said becoming the youngest grandmaster will be “very difficult.”

Nevertheless, Tani is determined.

At home recently in Port Jefferson Station, Tani solved chess puzzles on a computer screen in rapid succession while a reporter asked about his goals.

“I’m still sharp. I’m not old yet,” he said, explaining his ability.

After a few more puzzles, he added: “My biggest goal is to become youngest grandmaster. I will make it. I trust myself.”

Title photo by Newsday / Thomas A. Ferrara

Out East: Mecox Bay Dairy, Kent Animal Shelter, Custer Institute & Observatory and local champagnes NewsdayTV's Doug Geed takes us "Out East," and shows us different spots you can visit this winter.