Camurati: NY gets serious on cyberbullying

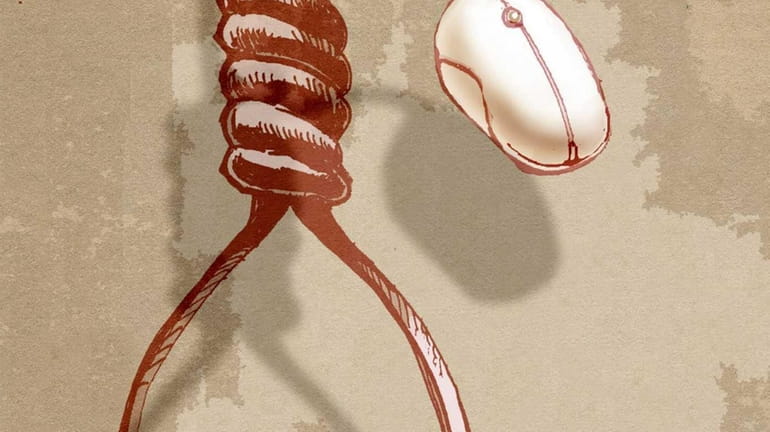

Cyberbullying legislation is a long time coming, but now it's up to the schools to follow through and protect the students. If only it were easier to protect them from each other. Credit: Paul Tong

When you're 15, awkward and mostly friendless, the proposal of an online friendship is thrilling. When you find out it was a group of girls -- I never learned who -- posing as a nonexistent classmate via instant messenger, giggling at you in the hallway as they watched your facial expressions change from glee to horror to humiliation, it sticks with you long after the first-period bell rings.

Legislators in Albany recently approved a new law legally defining cyberbullying as harassment, taunts, threats and insults "through the use of technology or electronic means." The law will require schools to designate a staff member to take "prompt action" on all reports of cyberbullying, to coordinate with police when appropriate, and to develop a curricular strategy for dealing with the problem -- both for training teachers and educating students.

It covers all electronic mocking on school property and at school functions and grants administrators authority over incidents outside of school if the bullying creates a hostile learning environment and disrupts the typical school day.

The legislation is a great starting point for combating an ever-growing torture method often unnoticed in schools. But is it enough?

Punishments aren't defined in the bill; disciplinary measures will be taken according to each school district's code of conduct. That means some bullies will be suspended or expelled, while others just get a couple days of detention.

Sen. Jeffrey Klein (D-Bronx) battled to have criminal charges added. Five of the 14 states with laws about cyberbullying slap on criminal charges. But even without defined penalties, the law should spur schools to take cyberbullying seriously.

Harsh criminal charges aren't necessarily the answer, though punishments should have enough impact to deter Web bullies from their childish yet destructive acts.

Part of what makes cyberbullying so rampant may be the lack of responsibility instigators feel for their actions. Hiding behind a username that isn't verified and a screen that doesn't react to the heinous words disconnects the bullies from their actions. If you can't see the deep damage you're inflicting on your target, it's no different from typing up homework.

In 2006, Megan Meier, a teenager from Missouri, was just as giddy as I was when she received a message from someone she didn't know but was "a friend of friends." She got to know 16-year-old "Josh Evans" for a few weeks. The two exchanged flirtatious messages but never met or spoke. One day, the messages she received turned mean and started coming from more than just the mysterious Josh. His last words to Megan were simple: "The world would be a better place without you." She hanged herself within an hour of the final correspondence.

Ryan Halligan of Vermont was bullied incessantly from the time he was 10 years old, both in school and online. Originally, the taunting was focused on his learning disability. After he learned to defend himself, the torment ceased -- but only briefly. Soon, a rumor that Ryan was gay surfaced, and the cruelty resumed. After three years of being picked apart by his peers, he hanged himself early one October morning in 2003.

Two tragic outcomes, but there's a difference between Megan's and Ryan's stories: Ryan confided in his father about some of the abuse, while Megan never told. Most students don't.

That's why teacher training is the most important aspect of this law. Children won't often be willing to readily admit that they're the center of attention in the most negative way. Telling a parent or teacher is embarrassing. Recognizing the signs and providing a comfortable environment for the student to open up is crucial. A committee at every school should be mandatory, not simply one teacher, and the entire staff needs to take action.

It's been almost 10 years since my experience, and thousands more have endured the pain since then, due to ineffective laws and a lack of consequences. This legislation is a long time coming, but now it's up to the schools to follow through and protect the students. If only it were easier to protect them from each other.

Amelia Camurati, an intern for Newsday Opinion, is a graduate of the University of Mississippi's Meek School of Journalism.