Fewer police for mental health crises

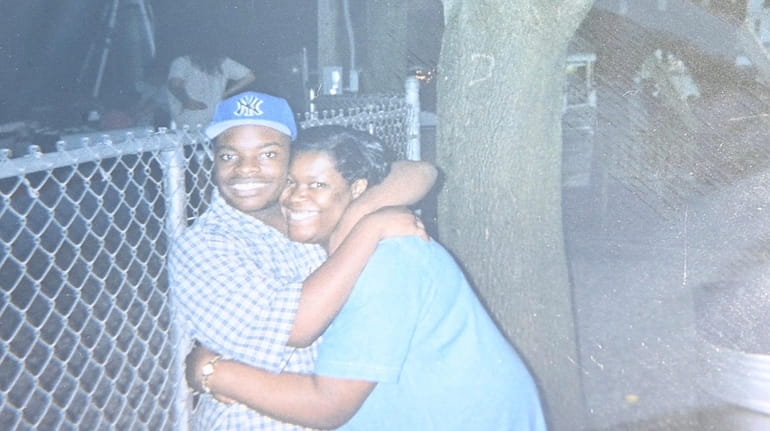

An undated photo of Dainell Simmons with his mother Glynice Simmons. Dainell, who was severely autistic, died while being subdued by police at a group home. Credit: Simmons family

Nine years ago, police responded to a Suffolk County group home after a 29-year-old Black man on the autism spectrum was reported to be behaving aggressively. Dainell Simmons had calmed down by the time Suffolk police officers arrived, according to a 2018 lawsuit and a Newsday report, but officers insisted on taking Simmons to a psychiatric hospital immediately. When Simmons resisted, officers used pepper spray and a Taser on him and forced him, facedown, onto the floor. Simmons died of asphyxiation.

Half of people killed by police have a disability, often a developmental disability like autism spectrum disorder or a mental health disorder like schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, according to a 2016 report by the Ruderman Family Foundation. The situation becomes even more dangerous for people of color. A 2020 study from the University of California Berkeley found that Black men displaying signs of mental illness are more likely to be killed by police than white men showing similar behaviors.

The Suffolk County Police Reform Task Force reports that 81% of police responses involve mental health, substance use, and homelessness, all of which should be social and medical issues, not criminal justice issues.

Across America, systems are in place to care for those experiencing behavioral health crises, avoiding violent and traumatizing encounters with the police. Many programs are modeled after Eugene, Oregon’s Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Streets (CAHOOTS), which provided mobile crisis intervention for 18,583 calls in 2019.

In Austin, Texas, the Expanded Mobile Crisis Outreach Team (EMCOT) trains dispatchers to divert mental health calls to trained counselors. According to EMCOT’s Integral Care Report, as of Sept. 1, 2020, 82% of the calls transferred by 911 call takers to mental health professionals were diverted from police response and received mental health support and short-term follow-up services.

The program has saved the city $1 million.

"911 call takers do the initial screening," said EMCOT’s Marisa Aguilar, a licensed professional counselor. "We have the ability to transfer back to police if we find that there are safety risks … We have never had an EMCOT responder harmed during a response."

The safety of first responders is paramount, as is the role of 911 dispatchers in these scenarios. In the recent incident in Harlem, where Lashawn McNeil shot and killed police officers Wilbert Mora and Jason Rivera, it is impossible to know whether a mental health response might have led to a different outcome. What we do know is the vast majority of people with mental illness are not violent. In fact, the American Psychological Association notes that "people with severe mental illness are over 10 times more likely to be victims of violent crime than the general population."

In 2020, former President Donald Trump signed into law a bipartisan bill to designate "988" as a national hotline for mental health emergencies. The hotline takes effect in July and is another step toward diverting behavioral health calls away from the police.

In New York, there is an effort underway to pass Daniel’s Law, named for Daniel Prude, who died in 2020 after an acute mental health and substance use crisis led to a violent encounter with Rochester police. This law would ensure that mental health professionals trained in de-escalation strategies and compassionate care are the first responders for behavioral health crises.

After the murder of George Floyd, then-Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo issued an executive order requiring police departments across New York to submit plans to reform their departments, with guidance urging them to consider deploying social services personnel to mental health and substance use crises instead of or in addition to police officers.

Nassau County is expanding its mobile crisis unit. Suffolk has created a 911 call diversion program that is in its infancy. Both counties need to understand that anything short of a full commitment to a cultural and structural change will result in failure.

This guest essay reflects the views of writer and activist Sonia Arora and clinical social worker and SUNY Empire State College associate professor Rebecca Bonanno, co-chairs of Transforming Crisis Response, a work group of Long Island United to Transform Policing and Community Safety.