Hunt: One-term presidents don't rate with historians

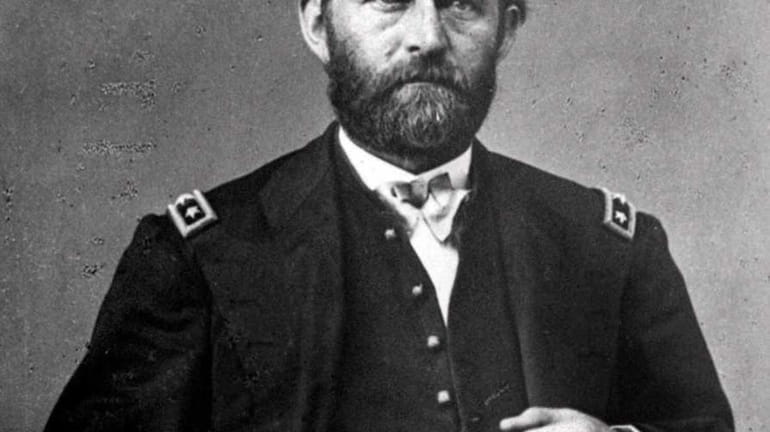

Lt. General Ulysses S. Grant poses for Mathew B. Brady. (1864) Credit: AP

U.S. political junkies are being treated to a feast this summer: David Maraniss' acclaimed new book on Barack Obama, the durable Mitt Romney biography by two Boston Globe reporters and, of course, another installment of Robert Caro's classic series on Lyndon Johnson.

After reading those, you also might want to pick up Robert Merry's "Where They Stand: The American Presidents in the Eyes of Voters and Historians," an analysis of how presidents fare with historians and why. It would make especially instructive reading for Obama and Romney.

The inspiration for Merry, a former top Washington reporter and editor and author of three other books dealing with U.S. politics, was an interview with Obama in which he said he'd "rather be a really good one-term president than a mediocre two-term president." Merry discovers that's pretty much a historical non-sequitur. The only one-term president who rates high in historians' surveys is James Polk, who acquired the Oregon territories and California and annexed Texas after a war with Mexico. (Merry has written a biography of Polk, a thoroughly pedestrian man who has been described as America's "least-known consequential president.")

Great presidencies usually are born through crises. Abraham Lincoln preserved the Union. Franklin Roosevelt led the nation through the Great Depression and World War II. George Washington defined the office. Every major survey considers those the three greatest. (The Lincoln-era bookends James Buchanan and Andrew Johnson are invariably rated among the worst.)

Bill Clinton complained that he didn't face a big crisis to prove his greatness. "I would have preferred being president during World War II," he once lamented, according to Bob Woodward's book about his presidency.

Yet a few great presidents were able to forge their own legacies. Theodore Roosevelt was the original trust-buster, initiated federal regulation to protect average citizens and launched the conservation movement; in foreign affairs, he ensured the completion of the Panama Canal and negotiated an end to the Russo-Japanese war, receiving the Nobel Peace Prize.

Woodrow Wilson, who Merry suggests is overrated, was president during World War I; that was in his second term, which is universally rated a failure. It was his first term, when he helped establish the Federal Reserve and the Federal Trade Commission, and enacted the federal income tax, that wins plaudits. He was a supporter of women's suffrage, though a racial bigot.

It's interesting how kind history is to a select few. Harry Truman didn't run for re-election in 1952 because he was embarrassingly unpopular. Yet within a decade, his extraordinary first-term accomplishments -- the Marshall Plan and Truman Doctrine, saving Western Europe from communism, forging international organizations, such as the United Nations, and the realization that the decision to drop the atomic bomb on Japan may have saved the lives of 1 million U.S. soldiers, marines and sailors -- saw him steadily climb in surveys. He is now rated among the top seven or eight greatest presidents.

Almost all his achievements were in that short first term. Merry would argue that without the validation of re-election his place in history wouldn't be as lofty. (Merry serves on the Board of Advisers of Bloomberg Government, which is owned by Bloomberg LP.) Another interesting case for revision is Ulysses S. Grant. The great Union Civil War commander generally was judged to be a terrible president whose time in office was wracked by scandal and by the destructive Reconstruction. That was a fairly accepted view until recently when Eric Foner, a Columbia University historian, argued that it was the suppression of Southern blacks that followed Grant's Reconstruction that is the real post-Civil War shame. Grant still ranks in the lower half of presidents, but no longer at the bottom.

Merry writes about the genius of the presidency that emerged from the 1787 Constitutional Convention; it was an office with virtually no precedent. Alexander Hamilton argued for an all-powerful president who would serve for life; others wanted the chief executive to be an appendage of the legislative branch. The compromise was to fashion a powerful presidency subject to checks and balances with delegated powers. This has survived for more than 200 years and is a model for countless other nations.

The lessons for the candidates this year are clear, the author said in an interview; they have to campaign "with an eye to governing," which is the only way to translate a victory into a mandate. He also hopes that Romney, as well as Obama, will appreciate the folly of the good one-term president theory; single-termers are usually history's losers.

Merry refers throughout the book to what he believes is one of the best indicators of electoral outcome, the 13 keys formulated by the political scientist Allan Lichtman and the journalist Ken DeCell three decades ago. These include conventional yardsticks such as economic growth and control of Congress, as well as domestic and foreign-policy achievements and the lack of any scandal or social unrest.

As of today, the Lichtman-DeCell keys show Obama on the positive side for nine of the 13, which points to an incumbent victory.

Writer Albert R. Hunt is Washington editor at Bloomberg News.