Editorial: Watergate lessons unlearned

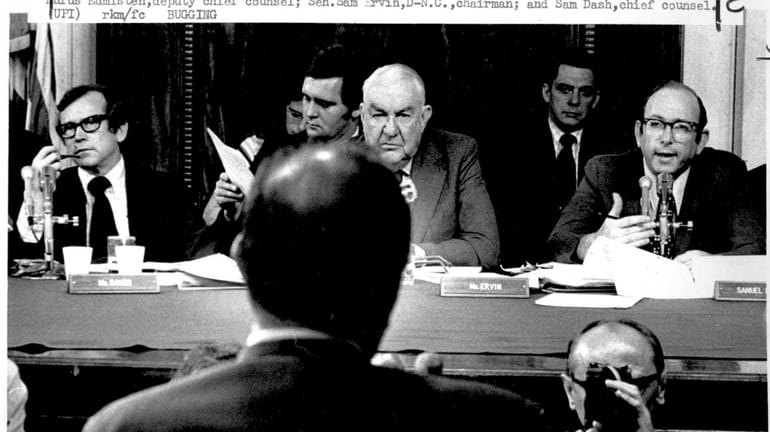

John Ehrlichman, President Richard Nixon's ousted domestic affairs adviser, foreground, tells the Senate Watergate Committee July 24, 1974, that Nixon sought unsuccessfully to get a factual account of the bugging scandal. Credit: UPI

Forty years ago today, Washington, D.C., police arrested five burglars in business suits at the offices of the Democratic National Committee. The name of the office-residential complex -- Watergate -- has since become synonymous with scandal.

That fateful break-in, authorized by aides to a president who would have trounced his opponent that November without even campaigning, led to Richard M. Nixon's resignation two years later. Nixon's "plumbers," the men who carried out such activities for him, were born of a president's paranoia and operated at a time of tremendous national discord over Vietnam.

Watergate undermined national faith in government. But it also spurred reforms intended to rein in presidential power, clean up federal campaign finance, make it easier to investigate government wrongdoing and restore the public's trust in its elected leaders.

Four decades later, those reforms are largely a failure.

Start with election reform. Legislation adopted in 1974 limited contributions to federal campaigns, established public financing for presidenetial races, and imposed new disclosure requirements. But since then constraints on campaign spending have all but vanished under a rising tide of cash. In 2008 Barack Obama became the first candidate to forgo public financing in exchange for the right to raise unlimited funds. Since then court rulings have opened the door to almost limitless contributions to separate but congruent organizations by individuals, corporations and unions.

And the hope that independent counsels, better known as "special prosecutors," insulated from political interference under post-Watergate reforms, could efficiently ferret out wrongdoing has been hopelessly tarnished since the investigation of President Bill Clinton by Kenneth Starr. Experience has proved these probes to be expensive and distracting fishing expeditions.

The public was outraged by disclosures of domestic spying by the Nixon administration. Yet those efforts pale next to the surveillance apparatus put in place since the 9/11 attacks. Advances in technology in the past 40 years have made possible vastly more government monitoring of communications -- and vastly more data-gathering by business as well, yielding data that government can access.

Indeed, the post-Watergate reform legacy has unraveled to a great extent since the 2001 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon. The USA Patriot Act was hurriedly adopted in October of that year, and hugely expanded government surveillance powers, enabling Uncle Sam to access, for example, an individual's phone records without that person even knowing about it. The law would have been unthinkable in the immediate aftermath of Watergate.

At that time, power swung away from Nixon's "imperial presidency," in part by disillusionment over Vietnam. In 1973, for instance, Congress adopted the War Powers Resolution over Nixon's veto. The law says a president undertaking military action has to get congressional approval within 60 to 90 days or terminate the action. Since then, the pendulum has reversed course toward the White House. And it gained momentum after the 9/11 attacks, which emboldened the White House to seize or kill enemies, hold captives without trial and make war by new or old means without explicit congressional approval. Presidential secrecy has only expanded since Nixon reigned.

Presidential power post-Watergate was partly checked by public skepticism toward Washington. That skepticism is still warranted. But following the 9/11 attacks, voters understandably rallied around the flag -- and the government. People supported increased domestic security measures and reflexively accepted President George W. Bush's dubious rationale for the invasion of Iraq -- at a terrible cost.

Given these many post-Watergate changes, perhaps the best way to mark the 40th anniversary of the break-in is to think about how our country can restore a proper balance between freedom and security.

We can start by insisting on more protections for our civil liberties against incursions by government and private data-gatherers. We can demand more congressional oversight of American war-making -- something that would be much easier absent such toxic congressional partisanship. And in the area of campaign finance, we need full disclosure of exactly who is spending what, especially the donors to insidious super PACs that supposedly maintain arm's-length separation from campaigns. Disclosing who is spending on our elections may help us understand why they are doing so.

Abuse of power is not new in Washington -- on the contrary, it long predates Watergate. It was naive for anyone to think that abuses wouldn't recur after the Watergate scandal faded. New betrayals didn't take long; the Iran-Contra weapons-for-hostages scandal, during the Reagan years, surely qualified. So did misinformation about Saddam Hussein's weapons of mass destruction.

It means the most important lesson of Watergate is one we should all have known: that constant vigilance truly is the price of liberty. Or, in the idiom that has become a legacy of Watergate: What must the people know and when should they know it?