Say Hey Kid, Willie Mays, still holding court at Giants camp

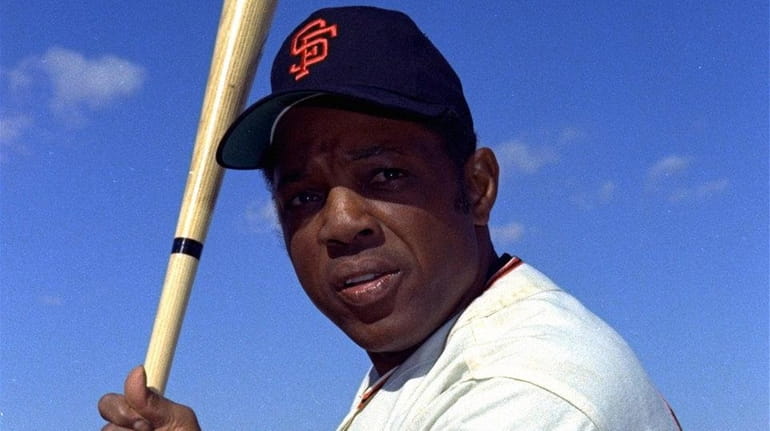

Willie Mays, near the end of his career with the San Francisco Giants in 1971. Credit: AP

Hall of Fame sportswriter Art Spander, a frequent contributor to Newsday, spent part of Tuesday with Willie Mays, whom he has covered since the 1960s, and posted this account on artspander.com, his blog.

SCOTTSDALE, Ariz. — Baseball still gets down to one person throwing a ball — pitching — and another trying to hit it. As it has been for 150 years. Before analytics and metrics.

When scouts saw a kid who could do it all and told management, “Sign him.”

A kid like Joe DiMaggio. Or Stan Musial. Or the man who was holding court in the Giants’ spring training clubhouse, Willie Mays,

In an hour or so, Jeff Samardzija would make his first start of the exhibition season, work an inning and a third and allow four runs in a game San Francisco would win, 14-12, over the Diamondbacks.

Then Samardzija would head to his locker, at the opposite end of the clubhouse from the table where Mays sits any time he chooses, and lament the trend toward replacing pitchers by the book, not on how they were performing, and the obsession in the sport on items such as launch angle and spin rate.

The angle at which Mays launched balls during his Hall of Fame career never will be known. But he hit 660 home runs despite missing most of 1952 and all of ’53 when he was in the Army. (“I probably would have hit 40 each year,” he said unpretentiously.) He also played home games for 12-plus seasons at cold, windy Candlestick Park.

Oh, was he special. From the start.

“We got to take care of this kid,” Gary Schumacher, the publicist of the New York Giants, said in the 1950s. “We got to make sure he gets in no trouble because this is the guy — well, I’m not saying he’s gonna win pennants by himself, but he’s the guy who will have us all eating strawberries in the wintertime.”

At this moment, at his table, the top autographed by Mays — “They sell it for charity,” he pointed out — Willie was eating a taco and between bites asking for a Coke.

“No Cokes,” he was told. “They want the players to cut down on sugar.” So Mays settled for water.

Willie will be 87 in May. His vision is limited. “I’m not supposed to drive at night,” he said to a journalist who also has eye problems. “But I feel good.”

It has been said that one of the joys of baseball is that it enables different generations to talk to each other. A grandfather and his grandson, separated by 40 or 50 years, may have little in common except baseball. The game is timeless.

Three strikes and Mays was out. Three strikes and Buster Posey is out. Batters still are thrown out by a step. “Ninety feet between bases is the closest man has come to perfection,” wrote the great journalist Red Smith.

The closest any ballplayer has come to perfection is Mays. We know he could hit. He could run, steal any time he wanted, third base as well as second. Defense? The late San Francisco Chronicle baseball writer, Bob Stevens, said of a Mays triple, “The only man who could have caught it hit it.”

On Tuesday, writers were hitting it off with Mays when rookie pitcher Tyler Beede, the Giants’ first pick in the 2014 draft, sat down next to him. They are separated by 62 years — Beede is 24 — but instantly they began a conversation.

“Where you from?” Mays asked Beede, a star at Vanderbilt who is from Chattanooga.

“You play golf?” Mays asked.

Beede said he did. “Twelve handicap,” he added.

Mays laughed. “Got to watch you 12-handicap guys. Pitchers, they’re always playing golf. They have the time between starts.”

Willie was a golfer until he no longer could see where his shots landed. He started the game at San Francisco’s Lake Merced Golf Club, struggled for a while — “I can’t believe I can’t hit a ball that’s just sitting there, not moving,” he said when he was learning — but became accomplished.

Then Pablo Sandoval dropped by, almost literally, practically sitting in Mays’ lap and wrapping Willie in a bear hug. “I need some money. I’m broke,” Sandoval said. The two laughed.

Willie is rich. In memories and friends.