Dance? Debate? Basketball? Summer school on Long Island takes on a new look

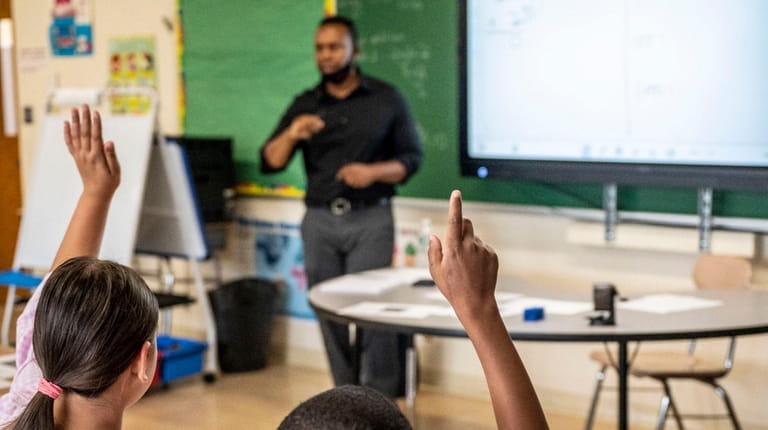

Summer school is underway in Amityville, where Nakia Wolfe instructs students. Credit: Newsday/Alejandra Villa Loarca

When Melanie Baker asked her son James to attend summer school this year, she told Newsday he was stunned and said, "What? I didn't fail anything."

It was only when the Brentwood mother explained that this year's summer school was not just about academics but also included "enrichment" activities such as volleyball and basketball that the middle-schooler agreed to go, Baker said in an interview.

"At first, I had to sell my son on the idea," Baker said of summer school, which began July 6. She added, "He's enjoying it. He's making new friends."

What to know

Many Long Island school districts have expanded summer school programs, as educators work to reclaim some of the lost learning due to the pandemic as well as make kids feel good and safe about school.

Boosted by $1 billion in federal stimulus money, districts are offering an abundance of new and exciting programs aimed at enticing students back to school, including sports programs, dance and art.

Educators say they are focusing on student's social and emotional well-being, following a year of pandemic shutdowns, quarantines and contact tracing.

Many Long Island school districts have reinvented summer school in response to a pandemic school year hampered by closures, quarantines and disrupted learning. Educators said the goal is to help students reclaim some of that lost learning, but more importantly to make them feel comfortable and excited again about school.

Long Island schools are being assisted by $1 billion in federal stimulus money, which they have three years to spend. Schools began the summer session in early July and will run programs into August.

Districts have added an abundance of programs — sports, art, music, dance — to attract more students. Moreover, educators said they are trying to move beyond the stigma of summer school as a place for failing students who sit for hours in a room drilling math problems.

"We are kind of making it exciting," said Freeport Superintendent Kishore Kuncham, whose district is offering dance, debate and citizenship among the usual academic offerings. "The key is the well-being of the kids."

Freeport schools Superintendent Kishore Kuncham. Credit: Chris Ware

So, is summer school actually becoming fun?

James Baker, 12, said yes.

"It's actually been quite good," said James, adding that he is taking a math class at Brentwood's East Middle School in addition to playing basketball and volleyball. "It's more like a summer camp than a school environment."

It's hard to make sweeping statements about Island schools, since there are 124 districts and each has local control. Some schools have vastly expanded their summer offerings, while others have stayed with their traditional approach. Many have removed the plastic shields around desks — they often became cloudy, making it hard for students to see — but districts have varying policies concerning the wearing of masks. Summer school is voluntary for students.

Making summer school fun

Amityville revamped its summer program from the ground up, Superintendent Edward Fale said. Like many Island districts, Amityville traditionally had its summer classes managed by BOCES, but this year the district took over the programs from prekindergarten through 10th grade. Programs for 11th- and 12th-graders are run by Western Suffolk BOCES, Fale said.

Amityville is spending about $1 million on the programs, with most of the money coming from the federal stimulus, Fale said.

The district has added, for example, a sports camp for kids in grades 3-5 from Aug. 2 to Aug. 13, which will have them playing soccer, softball and baseball.

Amityville could not accommodate all the students who wanted to attend summer offerings, Fale said. About 80% of the students were accepted, some 600, not including the upper grades handled by BOCES, Fale said.

Recruiting teachers was a challenge, the superintendent added. Many were burned out after a year of hybrid teaching amid masks and plastic barriers. So the district sweetened the incentive with a salary increase from about $53 an hour to $65 for summer instruction, and now has about 70 summer teachers, Fale said.

Traditional academic catch-up classes in math, English and science continue to be taught, but a major element of summer school is missing. The state had limited the number of Regents exams this school year and made them voluntary. Summer school is often populated by students looking to retake the Regents, but no makeup exams will be offered this summer.

Nakia Wolfe and students in Amityville. Credit: Newsday/Alejandra Villa Loarca

Inside Room 224 in Amityville's Park Avenue Memorial Elementary School, Nakia Wolfe is teaching math to about a dozen fourth-graders. Their desk guards are down, some kids are wearing masks and some not, as the district has made mask-wearing optional in classrooms.

Wolfe said he likes the smaller class size of summer school because it allows more individual attention. He sees students — some of whom were learning remotely for most of the school year — slowly reacquainting themselves with school.

The key to teaching summer school fourth-grade math — reinforcing adding and subtracting, as well as multiplication and fractions — is boiling the work down to the basic concepts, he said.

"It's about how to attack the problem," Wolfe said. "If you don't have those foundational skills, that's when deficiencies become disabilities."

The biggest challenges have come with those students who were learning remotely at home, said Wolfe, who is also head of the district's teachers union.

Educators are tempering expectations on how much of a school year they can cover in a few weeks of summer.

Are the kids in Wolfe's math class having fun?

"As much fun as you can have in summer school," Wolfe said.

More students, more teachers

Many classes are being held in-person this summer, though some remote instruction is available.

Some districts, such as Carle Place, continue to offer summer school through BOCES. Christine Finn, the district's superintendent, noted that Carle Place is a small district of about 1,300 students.

Finn said she has not seen much learning loss among the students, as the great majority have attended in-school classes since September.

Scope Education Services, a nonprofit based in Smithtown, is also working with about a dozen Island districts to provide summer enrichment classes. In Garden City, for instance, Scope is providing a course on jump-starting the college application process, including coaching on writing a college application essay.

Charles Russo, Scope's associate director, said his group is working with more than 7,000 students in Nassau and Suffolk, twice the amount in a typical summer. The group usually hires about 200 teachers but is now employing 400, he said.

This summer school also provides an opportunity to focus on students' emotional and social learning, said Nicole Galante, director of educational partnerships and innovation at Stony Brook University.

"We need them to feel safe before anything else," Galante said. "Summer school can be about reconnecting, sparking interest and curiosity."

As for making up the content from this last school year, Galante said it's not important that students read every novel and play assigned during the year, but that they learn the skills to analyze such works.

James Baker, the Brentwood 12-year-old who will begin seventh grade in the fall, said he initially hated the thought of attending summer school.

"I did not like the idea one bit," said James, adding he typically receives high grades. "I thought it would be boring."

But James said he's enjoying the games and sports in his gym class, as well as the guest speakers who talk about important life lessons.

"We're hearing about how to keep a healthy relationship with friends. How you always have to treat friends with respect," he said.

Not feel like punishment

Port Washington also is taking the reins of summer school from BOCES, at least for the elementary grades, Superintendent Michael Hynes said. BOCES is still providing the high school instruction, he said.

Whereas the district typically spends about $40,000 to participate in the BOCES programs, this year it will spend $400,000 of federal stimulus money for the summer programs, he said.

Port Washington schools Superintendent Michael Hynes. Credit: John Roca

Portraying summer school as fun is a hard sell, Hynes said. Importantly, he doesn't want it to feel like it's a punishment, not after everything kids went though this past year.

"I think they've been punished enough over the last 15 months," Hynes said. "I look at it as an extra step of support to help them get off on the right foot for the next school year."

Port Washington is not requiring students or staff to continue to wear masks in summer classes, in accordance with the recent directives by the state.

Freeport, however, is continuing to require masks in the building over the summer. Kuncham said he wants to err on the side of caution, even as he monitors the situation.

Kuncham said more than 900 children are attending summer school for grades K-8, almost double the number in a typical year. The number of students in secondary classes stands at about 400, a bit less than prior years, he said. The district is spending about $700,000 on summer schooling, most of it from federal stimulus money, he said.

These summer classes are offering students, particularly those in high-needs areas such as Freeport, opportunities usually reserved for more well-off kids who can go away to camp and on elaborate vacations, educators said.

Low-income, Black and Latino communities were among the hardest hit during the pandemic, in terms of both their health and their children's schooling.

Kuncham said the district has worked hard to bring those students into summer school, making phone calls and sending letters to parents and, when necessary, going to the student's home.

"We look at every child, and what every child is in need of, and what kind of assistance we can create," Kuncham said. "Whatever we need to do, we will do."