Nathan Hale was an unlikely, unprepared and unlucky spy.

Many grew up hearing Hale’s story: Early in the U.S. War for Independence, he crossed Long Island Sound to Huntington to gather information on British troop activity, and was captured and transported to Manhattan, where he was hanged after uttering one of the most famous quotes in history.

Yet many details related by historians about what happened to the young officer who volunteered to be Gen. George Washington’s first spy in the region have turned out to be speculation or just plain wrong.

Indeed, most historians agree he never said, "I only regret that I have but one life to give for my country." And much of his final week remains a mystery.

Scant historical record indicates that in the immediate aftermath of Hale’s death 245 years ago this month, nobody thought much about him. It was only at the end of the 18th century that his story began to be told.

And since then, historians have struggled to fill in the gaps. The missing details include where and how he was captured, where he was headed at the time, where he was hanged, where he was buried and what he said before British soldiers pulled a ladder out from under him after placing a noose around his neck.

New research by Claire Bellerjeau, historian at Raynham Hall Museum in Oyster Bay, has clarified the speed with which Rogers caught up to Hale. In January, after years of searching, she obtained from The National Archives in England copies of pages from the logbook of HMS Halifax, the British warship employed by Lt. Col. Robert Rogers to hunt Hale. The logbook gives the date and location where Rogers went ashore near Sands Point on Long Island Sound to pursue a spy or spies, helping to clarify the timeline of Hale’s final days.

While historians have referenced the Halifax logbook since the early 1800s, Bellerjeau said no one before her is known to have used its detailed entries to help determine when Rogers came aboard, when he went ashore to chase Hale and where that occurred.

"This evidence from the logbook — a contemporary, primary source — corrects the historical record and enables more accurate tracing and dating of Hale’s movements," said Natalie Naylor, professor of history emeritus at Hofstra University and past president of the Nassau County Historical Society.

Added Oyster Bay Town Historian John Hammond, "What Claire has done is wonderful. It proves that just because someone wrote something down in the 1800s it doesn’t mean that is true."

Bellerjeau became interested in Hale a decade ago when she noticed that Robert Townsend, who lived at Raynham Hall and became the chief spy in New York City for the Culper Spy Ring, was a footnote in the account of Hale’s demise in Henry Onderdonk Jr.’s 1849 book, "Revolutionary Incidents of Suffolk and Kings Counties." That research also led to her the little-known spy David Maltbie (see sidebar).

"I knew that the Halifax was important to the story because Robert Townsend is quoted as having spoken to Capt. William Quarme of the Halifax," she continued. "So I wanted to find that primary document and see what it said."

Quest for intelligence

When the American Revolution began, Washington knew he would have to match the sophistication of his enemy’s espionage system to have any success against the greatest military power in the world. After being caught off guard by British movements before and during the Battle of Long Island in Brooklyn in August 1776, the Continental Army commander-in-chief quickly took action to fill the intelligence vacuum.

Washington instructed Col. Thomas Knowlton to form a unit for reconnaissance and spy missions.

The most famous of Knowlton’s Rangers was Nathan Hale, invited to join in September 1776. The Connecticut native had in the fall of 1775 enlisted as an officer in the first of two Connecticut regiments after joining a local militia upon graduating from Yale University and working as a teacher.

After Hale volunteered, fellow officers tried to persuade him against what they viewed as a suicide mission. Yale classmate Capt. William Hull, wrote that "his nature was too frank and open … and he was incapable of acting a part …"

Hale left the Continental Army camp at Harlem Heights, in upper Manhattan, between Sept. 12 and 15. Posing as a Dutch schoolmaster, he traveled on foot to avoid suspicion. He was accompanied by a friend, Sgt. Stephen Hempstead, to Norwalk, Connecticut, where Hale thought he could find a vessel to carry him across the Sound without being intercepted by British warships.

In Norwalk, the novice spy encountered Charles Pond, a captain who had served with Hale in the 19th Connecticut Regiment. Pond agreed to ferry him to Long Island that night on his four-gun sloop Schuyler, which the Continental Army had commissioned to attack enemy vessels.

Near daylight on Sept. 16, Hale landed on the beach in Huntington, apparently planning to travel the North Shore to Brooklyn to gather information on British troop activities. Historians disagree over whether Hale’s plan was to report his findings to Washington in Manhattan or return the way he came.

A 1776 portrait of Lt. Col. Robert Rogers, who used the HMS Halifax to find the spy Nathan Hale. Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Worst possible pursuer

Hale’s inexperience and naiveté were compounded by bad luck — the man who would soon be on his trail.

Robert Rogers, an American hero as the commander of Rogers’ Rangers during the French and Indian War, had been commissioned by British Gen. William Howe as a lieutenant colonel to raise the Queen’s American Rangers to operate on Long Island and the Sound. Howe placed the Halifax at Rogers’ disposal.

After Hale was transported across the Sound, the Halifax’s Capt. Quarme received word from informants about two rebel vessels — Schuyler and Montgomery — observed in the area along with Continental Army soldiers.

Some historians have written that Rogers, assuming the vessels had transported one or more spies to Long Island, was aboard Halifax, a brig of 16 guns sailing off Huntington, and immediately set out in pursuit. It is generally accepted that Rogers came ashore in modern-day Sands Point. But historians disagree about whether Hale was captured in Great Neck, Huntington or elsewhere.

Now the chronology and the geography have been further clarified by Bellerjeau’s new parsing of the logbook entries.

The day after Hale’s crossing, Quarme wrote in the logbook for Sept. 17 in Huntington Bay: "Received by a Sloop Col. Rogers and a Battalion of Rangers at ½ past 9. Sent the tenders and boats armed to search the Bay for two Rebel Privateers having Intelligence of them."

Quarme wrote the next day that "the tenders and boats returned not being able to find any Rebel Privateers."

On Sept. 20, the logbook states: "At three came too [halted] off Hampstead Bay [Hempstead Harbor] … The Party of Rangers landed on Sansey’s Point." This was probably the Sandy Point at the north end of the peninsula noted on maps of the era, said Bellerjeau. Unlike earlier chronologies, the logbook makes clear that it only took Rogers one day ashore to catch up to Hale.

This 1905 drawing shows Nathan Hale disguised as a schoolteacher. Credit: Library of Congress

Traveling east or west?

Rogers suspected the spy or spies would be heading west gathering information. But historians disagree about Hale’s and Rogers’ movements leading to Hale’s capture. Initially, most historians believed Hale traveled west and was caught around Great Neck on his way to report to Washington in Manhattan.

More recently, historians and Hale biographers have said Hale’s plan was to travel west, then double back to Huntington to rendezvous with Capt. Pond and return across the Sound.

Either way, Rogers quickly picked up the trail of the young spy who was asking suspicious questions about British troops and the loyalty of citizens. By the end of the day he landed, Rogers caught up to Hale and prepared a trap.

But where? Bellerjeau found that in the Onderdonk history, Robert Townsend "had said Hale was captured near Huntington and that he had spoken to Capt. Quarme about that." Another Oyster Bay resident, William Ludlum, was quoted in a letter she found in the Brooklyn Historical Society saying that Hale was captured near Huntington. Ludlum had told Ebenezer Seeley that "one of Capt. Quarme’s boats took a man by the name of Hale somewhere near Huntington Harbor and then the man was taken to New York."

In the account offered by most historians, when Hale took a room at a tavern and sat down for dinner, Rogers joined him. After small talk and drinking, Rogers said he was also a Continental soldier gathering information on the enemy. Hale then revealed his own identity and secret mission.

Historians agree that Rogers, wanting Hale to confess in front of witnesses, suggested they meet for breakfast the next morning where Rogers was staying. Hale agreed. The next day, Rogers was accompanied by several of his rangers.

An artist's interpretation in an 1860 edition of Harper's Weekly depicts the execution of Nathan Hale in Manhattan. Credit: Library of Congress

To the gallows

When Hale again incriminated himself, Rogers stunned the spy by arresting him. Rogers transported his prisoner by water to Howe’s headquarters in Manhattan. In addition to wearing civilian clothes, Hale had intelligence notes hidden in the soles of his shoes. Howe quickly signed a death warrant.

After breakfast on Sept. 22, Hale was marched to his execution by Provost Marshal William Cunningham and his men. Most historians place the execution in an "artillery park," where cannons were stored, at what is today Third Avenue and 66th Street. Other writers put it in an apple orchard but disagree on its location.

The provost marshal chose a tree, and a rope was thrown over a branch. The condemned man climbed a ladder with a noose around his neck.

There is no contemporaneous record of Hale saying "I only regret that I have but one life to give for my country" — though British officers described him as dying bravely. Most historians dismiss the quote as apocryphal, tracing it to "Cato," a popular play of the time by Joseph Addison.

Cunningham left Hale’s body decomposing in the heat for three days. A slave finally cut down the corpse and buried it in an unmarked grave believed to be somewhere near Third Avenue between 46th and 66th streets, according to historians.

Washington never spoke or wrote of Hale’s death, nor was it announced to the troops. It was noted without detail in the Continental Army records: "Nathan Hale — Capt — killed — 22d September.

If Hale had survived, his intelligence would have been uselessly out of date because of the British’s rapid advance.

Hale’s inauspicious early attempt at espionage apparently had one positive effect. Lessons learned resulted in the creation of a much more effective network: the Culper Spy Ring. Organized in 1778 by a group of longtime friends from Setauket, it would help Washington win the war.

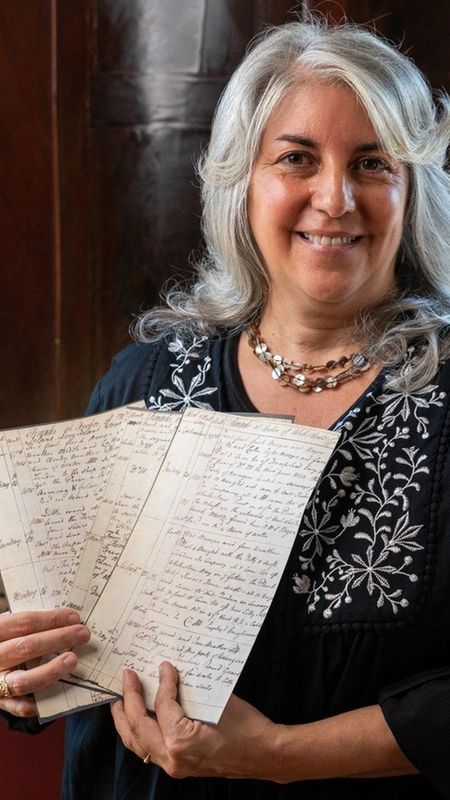

Claire Bellerjeau in August at David Maltbie's grave in Stamford, Connecticut. Credit: Chris Bellerjeau

Introducing David Maltbie

About the time Nathan Hale made his unsuccessful one-way trip to Long Island to spy on the British for George Washington, another Continental Army soldier from Connecticut crossed the Sound on a similar mission with a better outcome.

Unlike Hale, David Maltbie is mostly unknown.

But while Hale was captured once, Maltbie was captured twice — first in Oyster Bay, then in Manhattan — somehow avoiding the hangman’s noose both times.

The story of the spy from Stamford, Connecticut, has been partially unraveled by Claire Bellerjeau, historian at Raynham Hall Museum, the former home of the Townsend family in Oyster Bay.

In 2015, Bellerjeau was examining letters at the Brooklyn Historical Society written in the late 1840s by historian Henry Onderdonk Jr. to Ebenezer Seeley, who married Phebe Townsend and became the owner of Raynham Hall. "He had heard stories of the Revolution from people who had lived through it," she said. "I was pretty surprised to read this brand-new spy narrative," she said.

Onderdonk learned about Maltbie from Elizabeth Wooden, who as a girl had brought food to Maltbie after his first capture. Condemned to die, the spy escaped from a building at the southeast corner of what is today East Main Street and South Street in Oyster Bay.

Maltbie was only 18, three years younger than Hale, when he began spying. "Maltbie had the same cover story" of being a schoolteacher, Bellerjeau said the letters revealed.

But rather than traveling around Long Island and pretending to be a schoolteacher, Maltbie began teaching in Oyster Bay, where he stayed.

He sent letters — supposedly to his family back in Stamford but really destined for the commander-in-chief — via a man named Seeley who had a boat. Possibly an ancestor of Ebenezer Seeley, the man was a Loyalist. Becoming suspicious of Maltbie because of the volume of correspondence, Seeley apparently broke the wax seal on a letter, though it’s not known when.

When he read that Maltbie had written "500 men could easily beat the British in Oyster Bay," he reported the spy to the British. Maltbie was apprehended when attempted to flee across the Sound. Tried and sentenced to hang, he escaped incarceration.

Bellerjeau found references in old newspapers to Maltbie’s second arrest, in New York City in 1783. He was held at the Provost, a large jail. Bellerjeau found the date of his scheduled trial but no proof it occurred.

"We do know that he continued to live in Stamford after the war," she said. Maltbie was in the fur and skin business and was a local official in Fairfield. He married in 1786, died in New York in 1807 at 48 and was buried in Stamford, according to documents including newspaper ads, burial records and internet sources.

"What Claire has discovered about Maltbie is wonderful," said Oyster Bay Town Historian John Hammond.

Bellerjeau, whose 2021 book, "Espionage and Enslavement in the Revolution: The True Story of Robert Townsend and Elizabeth" (Lyons Press), is the first known to mention Maltbie, will speak about him on Sept. 12 at Raynham Hall, where he is included in a new exhibit; visit raynhamhallmuseum.org for details.

Claire Bellerjeau points to an entry in the HMS Halifax logbook that notes the ship coming ashore Sept. 20 in modern-day Sands Point. Credit: Corey Sipkin

The new Nathan Hale timeline

Claire Bellerjeau’s research fills in the historical details from Sept. 17 to 20.

Sept. 16, 1776: Hale lands in today’s Halesite.

Sept. 17: British Lt. Col. Robert Rogers and soldiers from his Queen’s American Rangers go aboard HMS Halifax in Huntington Harbor abd use the ship to search for reported spies who had come ashore the previous day.

Sept. 19: HMS Halifax anchors in "Hampstead Bay," today’s Hempstead Harbor, in the evening.

Sept. 20: Rogers and his men go ashore, where Rogers and Hale have dinner together.

Sept. 21: Rogers has breakfast with Hale, arrests him and takes him to Manhattan.

Sept. 22: Hale is hanged in Manhattan.

Updated 2 minutes ago The big dig begins ... Latest on transportation woes ... Find out if your school is closed ... Today's forecast