For many Long Island vets, pandemic means emotional, physical turmoil

After seven months of forced isolation, East Meadow Vietnam veteran Steven Rose had enough.

Too many days separated from friends, family and the support group that had kept him going in his darkest hours. The constant stream of bad news seemed never-ending, bringing with it a daily dose of monotony and lethargy. Anxiety and depression had set in, further exacerbating the combat Marine’s post-traumatic stress disorder.

And with the pandemic raging across the nation, there seemed to be no end in sight.

"There were days I said to myself, ‘Where’s this going? What’s the point?’" said Rose, 75, a retired school social worker. "Sometimes I just close the door and just want to be left alone."

For the nearly 100,000 veterans living on Long Island, the COVID-19 pandemic has been a constant source of physical, emotional and economic turmoil.

An untold number of veterans, likely several hundred, experts say, including at least 88 from the Long Island State Veterans Home at Stony Brook, have succumbed to the deadly virus, officials said.

Virus leads to turmoil

But below the surface, the coronavirus has had a detrimental effect on the lives of thousands of vets, from their ability to pay the mortgage to the closure of dozens of local American Legion halls — often among their few sources of socialization.

Drug and alcohol clinics have seen upticks in calls for service, including from patients identifying themselves as veterans. And the Nassau and Suffolk police departments have reported hikes in reports of domestic violence involving veterans although there is no data specifically on vets.

The Response Crisis Center in Stony Brook, a volunteer-based suicide prevention hotline, has seen a 27% increase in calls from March through the end of October, according to executive director Meryl Cassidy. Since the pandemic began, the center's hotline has handled 457 calls from individuals identifying themselves as veterans — an increase of 8% from one year prior, she said.

"The main presenting reasons for calls revolve around loneliness and isolation," Cassidy said, "particularly due to COVID, financial hardship, substance abuse, mental health concerns, relationship issues and homelessness."

State Sen. John Brooks (D-Seaford), chairman of the Veterans, Homeland Security and Military Affairs Committee, worries that wide-scale mental health issues are going unaddressed — and will be even more difficult to assist because of long-term funding deficits.

“Mental health is the elephant in the room and it’s not just the veterans.

State Sen. John Brooks, chairman of the Veterans, Homeland Security, and Military Affairs Committee

"Mental health is the elephant in the room and it’s not just the veterans," said Brooks, who held a hearing in August about the effects of COVID-19 on the veteran community. "We really have significant mental health issues and need to do a lot more to open up agencies."

The lockdowns, which began in early March, had a deleterious effect on many veterans, particularly among the older and less tech savvy, said Jeff McQueen, executive director for the Mental Health Association of Nassau County in Hempstead.

Being less computer savvy meant many veterans were too worried about contracting the virus to visit doctors and hospitals but unlikely to utilize telehealth, said McQueen, an Army veteran from East Rockaway.

For example, only 22% of veterans at the Northport VA Medical Center currently utilize some form of telehealth, according to Chad Cooper, a spokesman for the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Because the vets stopped seeing doctors, McQueen said, "whatever chronic illness that they may have been experiencing, or whatever ailments they may have had, they were not going to get access to care."

But the emotional toll may have been equally as devastating, said McQueen, who helps run the association's Joseph P. Dwyer Veterans Peer Support Project. Dwyer, an Iraq War veteran from Mount Sinai, struggled with post-traumatic stress disorder and died in 2008 of a drug overdose. The project provides peer support for veterans struggling with PTSD and other issues.

McQueen, who served in the Army 82nd Airborne in Grenada, said he’s received a high number of calls from family members of veterans who say their loved one lost friends to the virus and began drinking in excess.

"We are driven by mission," McQueen said of himself and other veterans. "As long as I have a mission or someone to take care of or things to do I am OK. But when the mission ends, then what? What do I do? So, I am sitting here and the noise in my head gets louder. The things that I am working so hard to keep away from me are now in the forefront of my life."

Isolation sparks mental distress

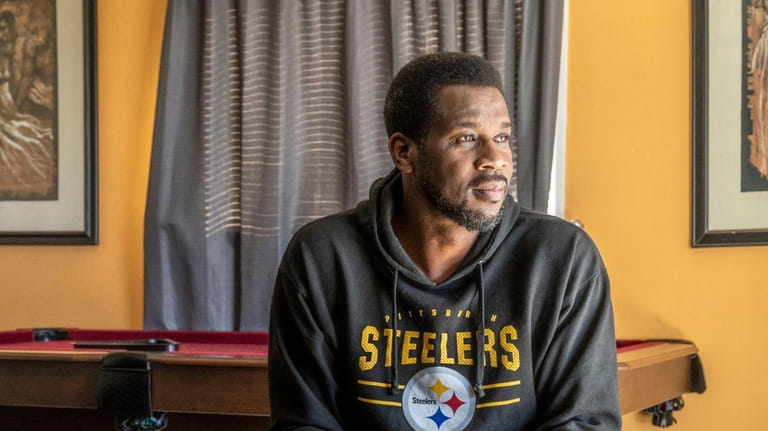

Former Iraq combat veteran Mike Green at his home in Baldwin on Nov. 2. Credit: Newsday/Alejandra Villa Loarca

Mike Green, 58, of Baldwin, who served 25 years in the Army and Marine Corps, said the isolation and lack of face-to-face contact during the lockdowns exacerbated his depression, anxiety and other PTSD symptoms.

Virtual appointments and counseling sessions, he said, served as a poor substitute, presenting few opportunities for the camaraderie and companionship he gets from being among his peers. Sleep, for years a serious problem for Green, became even more difficult. He would overeat at times and at other points limit himself to one meal per day.

"COVID intensified my hypervigilance," said Green, who served two tours in Iraq and recovered from COVID-19 in April. "There’s a run on water and food in stores. People going to the store buying guns and ammunition. As a military vet you are conditioned and need to get ready too. We are concerned about situational awareness."

We shifted on a dime from meeting at the diner to under no circumstances leaving your house. Lives were turned upside down.

Thomas Ronayne, head of the Suffolk Veterans Services Agency

Thomas Ronayne, head of the Suffolk Veterans Services Agency, said he would often encourage vets who tend to "self-isolate" and resist social interaction to meet at a diner for a cup of coffee. But that all changed in the spring.

"We shifted on a dime from meeting at the diner to under no circumstances leaving your house," he said. "Lives were turned upside down. We’ve seen instances of depression and anxiety disorders. Depression leads to alcohol and drug misuse, family stresses, job loss, financial and housing insecurity, unemployment and increases in domestic violence. All the rotten stuff has expanded under the pandemic."

Veterans across Long Island rely on a labyrinth of local, state and federal agencies, including the Department of Veterans Affairs, for a host of medical and financial services.

During the pandemic, the Northport VA provided lifesaving care to 402 COVID-19-infected patients while adhering to safety practices that limited its employee infection rate to less than 1%, Cooper said.

"Additionally," he said, "Northport VA’s Suicide Prevention Team has been reaching out to all patients who either screen or test positive for COVID-19 to assess adjustment and coping during these difficult times."

And it’s not just government agencies fielding increased requests for services.

Calls for aid spike

Dave Rogers, past county commander of the Suffolk County Veterans of Foreign Wars, said before COVID-19, his office would field about three calls for assistance each week. During the height of the pandemic, he received four to five calls per day, from rides to medical appointments to assistance paying rent and bills.

“We can’t help everybody, but we know where to send them and who to call.

Dave Rogers, past county commander of the Suffolk County Veterans of Foreign Wars

"We can’t help everybody," he said, "but we know where to send them and who to call."

Benjamin Pomerance, deputy director for program development at the State Division of Veterans’ Services, said the pandemic has brought a silver lining to the way vets receive services. For decades, vets would be required to come to an office and meet with a benefits adviser to process disability, pension and education applications, Pomerance said.

But with the pandemic limiting face-to-face interaction, New York created an electronic interface that would deliver claims packages to the VA without an in-person visit from the vet.

"COVID-19 forced a long overdue change in that realm," said Pomerance, who noted that his office has submitted 5,000 benefits claims, including from approximately 200 Long Island veterans, since March — largely without face-to-face interaction between agency officials and the claimant.

The economic anxiety stemming from the pandemic has also forced many veterans to local food banks for assistance.

Long Island Cares, which runs satellite locations in Freeport, Hampton Bays, Huntington Station and Lindenhurst that distribute food to veterans every Tuesday, said they’ve serviced 149 new vets since the pandemic began, an uptick of 12%, according to Michael Haynes, the organization’s chief government affairs officer.

Island Harvest, a food bank in Bethpage, has seen a 38% increase in pounds of food delivered to veterans from March to October compared with the same period a year ago.

And at the Nassau County Veterans Services Agency, director Ralph Esposito said that more than anything else, they are getting calls on food, housing and economic issues.

"A lot of people lost their jobs and are looking for a way out of this," Esposito said, "but it does not seem to be coming."

Helping my fellow vets seems to help me ... we take care of each other.

Steven Rose, Vietnam vet from East Meadow

Steven Rose, the East Meadow Vietnam vet, said he’s taking it day-by-day with the help of his family, the Dwyer project and Hawk, his English black Labrador service dog.

Rose said he tries to stay busy and plans meetings with other veterans in need of assistance. Helping others, he said, is the best therapy for his anxiety and depression.

"If I plan a day with positive things to do I am better," he said. "Other days I don’t want to be bothered. But helping my fellow vets seems to help me. We are a very integrated group and we take care of each other."