Some doctors call for tighter government oversight over fecal transplant procedures

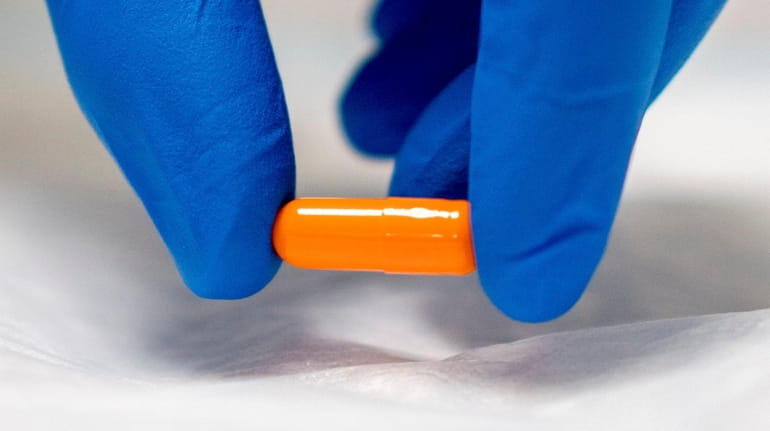

A specialist in infectious diseases at North Shore University Hospital in Manhasset has cured patients diagnosed with Clostridium difficile with "poop pills." Credit: Johnny Milano

For six years, Dr. Bruce Hirsch has been curing patients afflicted with one of the worst intestinal infections known to modern medicine by prescribing “poop pills,” capsules made in his lab using human feces as the active ingredient and sourced from a small group of Long Island donors.

Hirsch, a specialist in infectious diseases at North Shore University Hospital in Manhasset, is an expert in treating patients diagnosed with Clostridium difficile — or C. diff — an excruciatingly painful condition marked by intestinal cramping, fever and diarrhea. Thousands of people nationwide die annually from the infection.

The doctor has rescued hundreds of patients from C. diff by having them swallow 24 poop pills, 12 in each of two sessions held up to five days apart. He estimates a 90 percent cure rate.

“The pills are nested,” Hirsch said of a triple coating that encases the fecal matter — distancing patients from the main ingredient. There are two enteric coatings and a gel capsule that insulate the feces. “It’s one inside the other, inside the other, like a Russian doll.”

Swallowing the pills, which are given a citrus flavoring, constitutes a fecal microbial transplant, a procedure that reseeds each patient’s intestinal tract — the gut microbiome — with healthy new flora.

Yet, in recent weeks a cloud has emerged over fecal transplants with the first death of a U.S. patient, causing doctors like Hirsch to ask tough questions of government regulators. Other leading physicians are calling for tight federal oversight of the procedures and say it’s time to regulate medical uses of human feces as a prescription drug.

Problems in the fecal transplant arena surfaced in early June, when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced that two patients developed severe infections, and one died. Both were described as immunocompromised. Fecal matter from the donor contained highly pathogenic drug-resistant bacteria that infected both patients.

FDA officials have not revealed where the infectious transplants occurred or why the donor’s feces wasn’t thoroughly screened. The agency also has declined to reveal information about the two recipients, citing patient confidentiality laws.

“This makes me frustrated with the FDA for its paucity of information,” Hirsch said. “I want to know who those recipients were. Much of the information has focused on the donor, but I want to know about the patients — are there certain patients we should avoid?”

After announcing the death and illness involving fecal transplants, FDA officials followed with an embargo on clinical trials of fecal transplant procedures. A slew of studies — some offbeat — have surfaced in recent years.

C. diff therapies, such as Hirsch’s poop pills, and other fecal transplant methods for the condition were not included in the ban. Nevertheless, fecal treatments for C. diff, which fall under the FDA’s investigational new drug regulations, are still considered experimental by the agency.

Hirsch has successfully treated more than 200 C. diff patients since 2013, people ranging in age from their 20s to 103. And he is not the only specialist on the Island who has perfected the use of feces as medicine for C. diff.

Dr. Ellen Li, a renowned physician/scientist at Stony Brook University Hospital, also is treating C. diff patients. She performs fecal transplants in a different way: introducing donor feces through a colonoscope, a tube inserted through the rectum.

“There are patients who really have a tough time with C. diff,” said Li, a gastroenterologist who is also a professor of microbiology and molecular genetics at Stony Brook Renaissance School of Medicine. As an expert in the rarefied world of bolstering the human gut microbiome through fecal transplants, Li often works collaboratively with Hirsch.

“Dr. Hirsch and I have had patients who have talked about having their colons taken out,” Li said, because the pain and constant diarrhea are too much to bear.

Under FDA regulations, only patients who have had recurrent C. diff and whose infections were not cured with the standard of care, the highly potent antibiotic vancomycin, are considered candidates for fecal transplants.

C. diff is caused by the overuse of antibiotics, especially in hospitalized patients. The drugs wipe out healthy microbes in the gut, allowing pathogenic C. diff to prevail. The condition affects about 500,000 people in the United States annually and is the cause of about 14,000 deaths.

Both Hirsch and Li said feces used in their procedures is tested to ensure it’s free of pathogens. Donors also must undergo blood testing for syphilis and pathogenic viruses, such as HIV and hepatitis A, B and C, among others.

But while the FDA has allowed fecal transplants for C. diff to continue, untold numbers of clinical studies involving the procedures have been halted. Researchers have been conducting clinical trials using fecal transplants to address autism, anxiety, depression and obesity, to name a few.

A clinical study at Stony Brook involving patients with an inflammatory bowel condition — a sound reason for the transplants — was stopped, a move that saddened Li.

“If you’re going to do this, you need to know what you’re doing,” said Li, who called some of the emerging microbiome studies the new “snake oil.” Her opinion dovetails with the conclusion of a tough commentary by two doctors writing in a recent issue of the journal Nature Medicine.

Dr. Elizabeth Hohmann of Harvard and Dr. Kjersti Aagaard of Baylor College of Medicine in Texas are calling for tight regulations of fecal microbial transplants as the medical community embarks on the pioneering frontier of microbiome medicine. Tightening the rules could lead to the oversight of human feces as a prescription drug.

Hohmann and Aagaard contend there is a gap in scientific knowledge about benefits and risks involving the manipulation of the microbiome.

“When you transfer fecal matter, your goal is to transfer the gut microbiome of a seemingly healthy person to another less healthy individual. How do you know you haven’t passed on the risk of an illness or predisposition that could appear five, 10 or 20 years later?” they jointly asked.

ABOUT CLOSTRIDIUM DIFFICILE

Clostridium difficile, referred to as C. diff, is an infection caused by the overuse of antibiotics, especially in hospitalized patients. The drugs wipe out healthy microbes in the gut, allowing pathogenic C. diff to prevail. C. diff affects about 500,000 people in the United States annually and is the cause of about 14,000 deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.