With coronavirus vaccine coming to LI, a challenge: Winning over skeptics

When the long-awaited vaccines to stamp out the coronavirus pandemic become widely available next year, Mae Geddis of Roosevelt plans to forgo taking the shots.

"I’m torn. I don’t trust it," Geddis, 53, an elementary school administrative assistant, wrote in a text message. "There hasn’t been enough time to see what the side effects are."

The first of nearly 3 million doses were shipped Sunday, destined to be injected first into health care workers on the front lines, with the goal of inoculating enough Americans by spring to end the pandemic. But with just months until the general public’s turn to get vaccinated, government officials and disease-control experts are strategizing how to overcome a common reaction on Long Island and across the United States: No thanks.

Mae Geddis of Roosevelt, a lifelong Long Islander, says she's concerned about long-term side effects of the vaccination against coronavirus. Credit: Newsday/J. Conrad Williams Jr.

Only half of Americans are willing to get a coronavirus vaccine, according to a survey released Wednesday by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. That is short of the 75% to 80% immunity that Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation's top infectious-disease expert, estimates to be necessary for "herd immunity" to stop the virus from circulating. Incredulity is most pronounced among certain racial minorities: While 53% of whites say that will get vaccinated, the survey found, only 24% of Blacks and 34% of Hispanics do. A poll by Mount Sinai South Nassau hospital in Oceanside found similar results.

Vaccine development normally takes 10 to 15 years, but the race to pioneer coronavirus vaccines has taken less than 12 months to produce several viable options, some of which use relatively new technology.

There are pockets of deep distrust of coronavirus vaccination, particularly among Black Americans, borne of a long history of unethical medical research on Black people — such as the infamous, 40-year Tuskegee experiment: The U.S. government promised Black men with syphilis free health care, then secretly left them untreated so scientists could study the progression of the disease, which can turn fatal.

"The skepticism is beyond belief," said E. Reginald Pope Sr., Long Island's regional director of the Rev. Al Sharpton’s National Action Network.

But, worried how dangerous the coronavirus is, and how disproportionately it has infected Black people, Pope said, he plans to get vaccinated, and urged other Long Islanders to follow his lead.

"A lot of Black doctors, they’re endorsing that it’s safe and effective, the vaccine, and that we should take it. I feel, yes, we should take it. We gotta take it to stop the spread," Pope said. "People are dying."

The Nassau County health department’s equity director, Andrea Ault-Brutus, is among Long Island government officials tasked with figuring out how to maximize vaccination and ensure the distribution is equitable, regardless of factors such as race, ability to pay or legal immigration status.

"There’s going to be a lot to overcome to assuage the community’s concerns about the vaccine. There’s a long, horrible history of mistreatment," Ault-Brutus, who has a doctorate in health policy from Harvard, said of episodes such as Tuskegee.

Nassau will enlist "trusted individuals in the community to help us with delivering the message," she said.

Ault-Brutus and her team must surmount not just some minority Long Islanders’ skepticism, but reluctance among the wider population based on other factors.

"During this time, I know a lot of people don’t have a lot of confidence in government, and that’s across the board, whether you’re a Republican or Democrat. You know, unfortunately, there’s a lot of mistrust in institutions," she said. "So we have a lot to do."

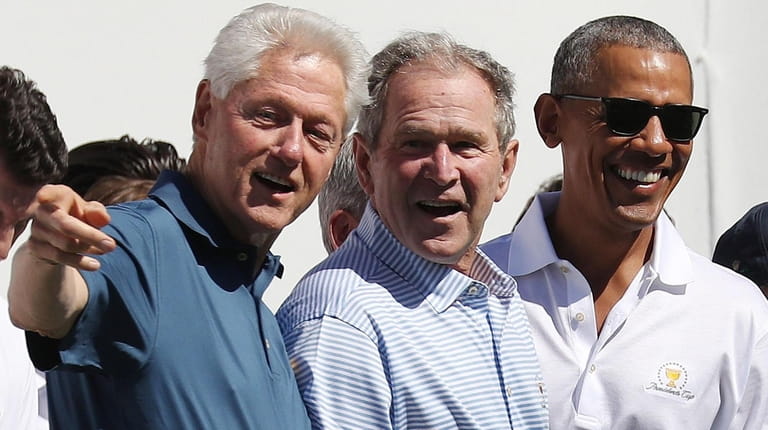

Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Barack Obama, shown in 2017, say they'll be publicly vaccinated against the coronavirus. Credit: ANDREW GOMBERT/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

Matt Motta, an assistant professor of political science at Oklahoma State University, said he is heartened that the three most recent past presidents — George W. Bush, Bill Clinton and Barack Obama — have promised to get vaccinated publicly.

"The people we're more likely to believe are the people with whom we already have something in common," Motta said. "Democrats are more likely to listen to Democrats. Republicans are more likely to listen to Republicans."

But since Bush, a Republican, may not represent much of the conservative mainstream anymore, Motta said, it’s important for Trump-supporting politicians to be among those backing vaccination.

Long Island's congressional delegation, clockwise from left, Peter King, Lee Zeldin, Kathleen Rice, Gregory Meeks and Tom Suozzi, all say they'll be vaccinated against the coronavirus. The group is shown at a Zoom meeting in the spring. Credit: Congressman Tom Suozzi/Via Zoom

Long Island's congressional delegation — Trump supporters Lee Zeldin (R-Shirley), the outgoing Peter King (R-Seaford) and his successor, Republican Andrew Garbarino, as well as Biden supporters Kathleen Rice (D-Garden City), Tom Suozzi (D-Glen Cove) and Gregory Meeks (D-St. Albans) — committed in statements to Newsday, directly or through spokespeople, to get vaccinated.

Earlier this month, Nassau County Executive Laura Curran launched a public-awareness campaign with the slogan, "We Can Do It, Nassau," depicting Rosie the Riveter, a fictional, patriotic mascot from the World War II era. The Nassau campaign, to be translated into several languages, is meant to "dispel false rumors with facts," she said.

The county plans to track local data and outside research to see what's working, what isn't, and modify strategy accordingly, said Jordan Carmon, an adviser to Curran.

Grace Kelly-McGovern, a Suffolk health department spokeswoman, said it is too early to discuss how the county would promote vaccination.

In New York City, Mayor Bill de Blasio said Friday he would direct prioritized outreach to nonwhite neighborhoods.

"We know there is a trust gap. We know a lot of people are uncertain about the vaccine. We have to win people over and show them why it works, why it's real, why they can believe in it," he said.

What doesn’t work with skeptics? Attempting solely to "fact-check" them into submission, said Motta, the political scientist, because vaccine refusal can be tightly intertwined with moral or religious or political beliefs.

"What a fact-check does is it assumes that people don’t know the facts, and that only if they were given the facts, they might come around," he said, later adding: "You can sometimes get people to change their mind. You can get people to say that they’re no longer endorsing misinformation about vaccines with a fact-check. But that doesn’t guarantee that they will then update their behavior."

Michael Kinch, a professor at Washington University in St. Louis who wrote the 2018 book "Between Hope and Fear: A History of Vaccines and Human Immunity," said that among the tens of thousands who have been part of the coronavirus vaccine trials, none have experienced any long-lasting, serious side effects. Most side effects would have happened within the days and weeks of administration, and the likelihood of long-term effects is "very, very low," Kinch said. The greater danger to the population, he said, is from the coronavirus, which as of early Monday evening had infected 16.4 million Americans and killed 300,420 of them.

"Frankly, we won’t be able to give anyone complete confidence that we don’t have long-term problems coming from the vaccines," he said. "That said, we have to look to history, and we don’t have many precedents where you do see those kind of toxicities arising later."

Some Americans — perhaps one-quarter — might never change their minds, he said. Geddis, the Roosevelt woman, appears to be in that camp. She said she will just keep on maintaining social distance, wearing a mask, and taking other precautions, rather than a vaccine, which is administered in two shots total, several weeks apart.

"I don’t think anyone can say anything to convince me. I would have to speak to someone that can tell me they took the vaccine a few years ago and they had no side effects," she texted, "or what the side effects were."

E. Reginald Pope Sr., right, in 2019 with his lifelong friend Bishop William A. Watson Jr., the pastor of St. John's Baptist Church of Westbury, who died in April of COVID-19. Credit: Newsday/Víctor Manuel Ramos

Undeterred, E. Reginald Pope Sr. of the National Action Network says he still hopes he can change minds, including by sharing memories of the 32 people he has lost this year to the virus.

"They were friends, and some was family," he said, "and it’s been very, very depressing."